After Dominic Cummings’ marathon session at the Select Committee, the Times published an article on,”The heroes and villains of the pandemic, according to Dominic Cummings”

One of Dom’s villains left out, was data protection law. He claimed, “if someone somewhere in the system didn’t say, ‘ignore GDPR’ thousands of people were going to die,” and that “no one even knew if that itself was legal—it almost definitely wasn’t.”

Thousands of people have died since that event he recalled from March 2020, but as a result of Ministers’ decisions, not data laws.

Data protection laws are *not* barriers, but permissive laws to *enable* use of personal data within a set of standards and safeguards designed to protect people. The opposite of what its detractors would have us believe.

The starting point is fundamental human rights. Common law confidentially. But the GDPR and its related parts on public health, are in fact specifically designed to enable data processing that overrules those principles for pandemic response purposes . In recognition of emergency needs for a limited time period, data protection laws permit interference with our fundamental rights and freedoms, including overriding privacy.

We need that protection of our privacy sometimes from government itself. And sometimes from those who see themselves as “the good guys” and above the law.

The Department of Health appears to have no plan to tell people about care.data 2, the latest attempt at an NHS data grab, despite the fact that data protection laws require that they do. From September 1st (delayed to enable it to be done right, thanks to campaign efforts from medConfidential et supporters) all our GP medical records will be copied into a new national database for re-use, unless we actively opt out.

It’s groundhog day for the Department of Health. It is baffling why the government cannot understand or accept the need to do the right thing, and instead is repeating the same mistake of recent memory, all over again. Why the rush without due process and steamrollering any respect for the rule of law?

Were it not so serious, it might amuse me that some academic researchers appear to fail to acknowledge this matters, and they are getting irate on Twitter that *privacy* or ‘campaigners’ will prevent them getting hold of the data they appear to feel entitled to. Blame the people that designed a policy that will breach human rights and the law, not the people who want your rights upheld. And to blame the right itself is just, frankly, bizarre.

Such rants prompt me to recall the time when early on in my lay role on the Administrative Data Research Network approvals panel, a Director attending the meeting *as a guest* became so apoplectic with rage, that his face was nearly purple. He screamed, literally, at the panel of over ten well respected academics and experts in research and / or data because he believed the questions being asked over privacy and ethics principles in designing governance documents were unnecessary.

Or I might recall the request at my final meeting two years later in 2017 by another then Director, for access to highly sensitive and linked children’s health and education data to do (what I believed was valuable) public interest research involving the personal data of children with Down Syndrome. But the request came through the process with no ethical review. A necessary step before it should even have reached the panel for discussion.

I was left feeling from those two experiences, that both considered themselves and their work to be in effect “above the law” and expected special treatment, and a free pass without challenge. And that it had not improved over the two years.

If anyone in the research community cannot support due process, law, and human rights when it comes to admin data access, research using highly sensitive data about people’s lives with potential for significant community and personal impacts, then you are part of the problem. There was extensive public outreach in 2012-13 across the UK about the use of personal if de-identified data in safe settings. And in 2014 the same concerns and red-lines were raised by hundreds of people in person, almost universally with the same reactions at a range of care.data public engagement events. Feedback which institutions say matters, but continue to ignore.

It seems nothing has changed since I wrote,

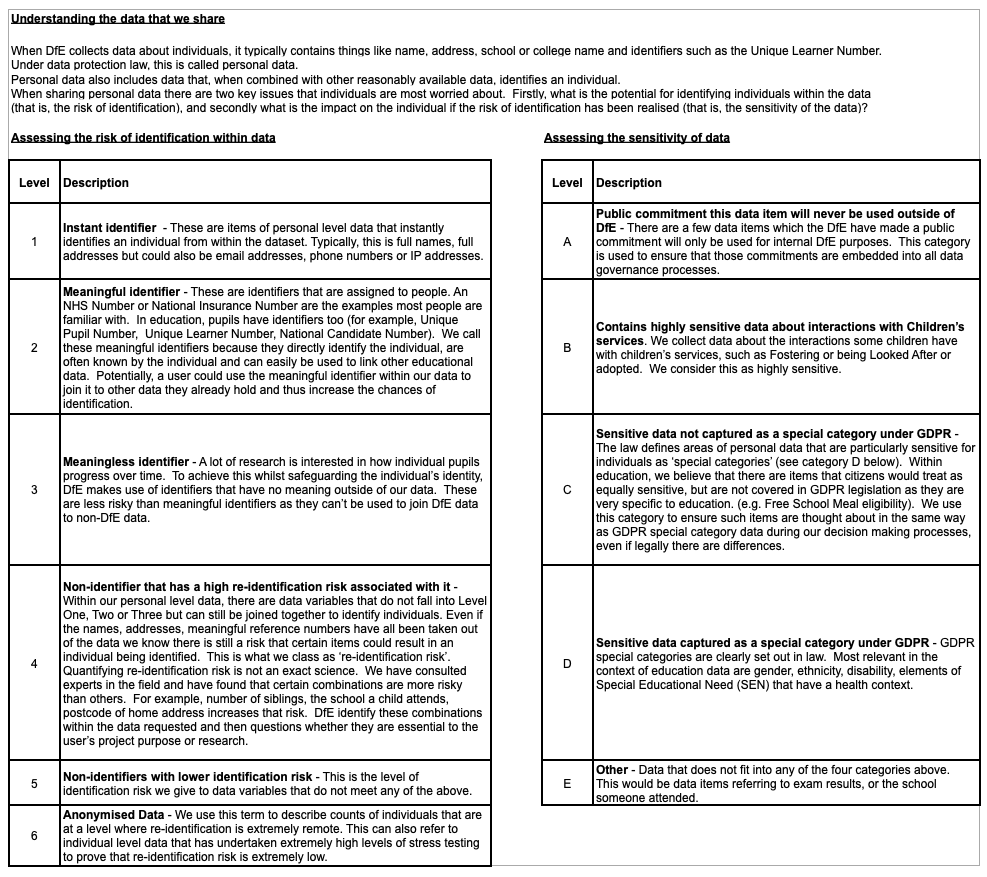

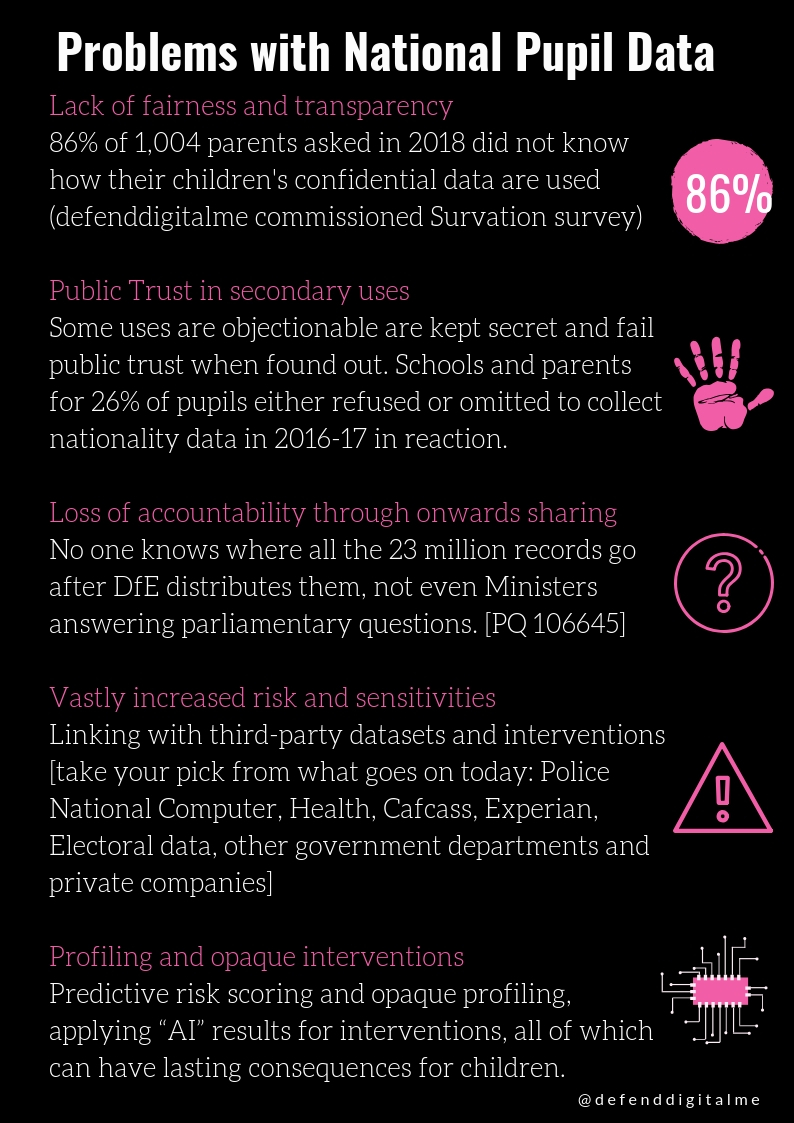

We could also look back to when Michael Gove as Secretary of State for Education, changed the law in 2012 to permit pupil level, identifying and sensitive personal data to be given away to third parties. Journalists. Charities. Commercial companies, even included an online tutoring business, pre-pandemic and an agency making heat maps of school catchment areas from identifying pupil data for estate agents — notably, without any SEND pupils’ data. (Cummings was coincidentally a Gove SpAd at the Department for Education.) As a direct result of that decision to give away pupils’ personal data in 2012, (in effect ‘re-engineering’ how the education sector was structured and the roles of the local authority and non-state providers and creating a market for pupil data) an ICO audit of the DfE in February 2020 found unlawful practice and made 139 recommendations for change. We’re still waiting to see if and how it will be fixed. At the moment it’s business as usual. Literally. The ICO don’t appear even to have stopped further data distribution until made lawful.

In April 2021, in answer to a written Parliamentary Question Nick Gibb, Schools Minister, made a commitment to “publish an update to the audit in June 2021 and further details regarding the release mechanism of the full audit report will be contained in this update.” Will they promote openess, transparency, accountablity,or continue to skulk from publishing the whole truth?

Children have lost control of their digital footprint in state education by their fifth birthday. The majority of parents polled in 2018 do not know the National Pupil Database even exists. 69% of over 1,004 parents asked, replied that they had not been informed that the Department for Education may give away children’s data to third-parties at all.

Thousands of companies continue to exploit children’s school records, without opt-in or opt-out, including special educational needs, ethnicity, and other sensitive data at pupil level.

Data protection law alone is in fact so enabling of data flow, that it is inadequate to protect children’s rights and freedoms across the state education sector in England; whether from public interest, charity or commercial research interventions without opt in or out, without parental knowledge. We shouldn’t need to understand our rights or to be proactive, in order to have them protected by default but data protection law and the ICO in particular have been captured by the siren call of data as a source of ‘innovation’ and economic growth.

Throughout 2018 and questions over Vote Leave data uses, Cummings claimed to know GDPR well. It was everyone else who didn’t. On his blog that July he suggested, “MPs haven’t even bothered to understand GDPR, which they mis-explain badly,” and in April he wrote, “The GDPR legislation is horrific. One of the many advantages of Brexit is we will soon be able to bin such idiotic laws.” He lambasted the Charter of Fundamental Rights the protections of which the government went on to take away from us under European Union Withdrawal Act.

But suddenly, come 2020/21 he is suggesting he didn’t know the law that well after all, “no one even knew if that itself was legal—it almost definitely wasn’t.”

Data Protection law is being set up as a patsy, while our confidentiality is commodified. The problem is not the law. The problem is those in power who fail to respect it, those who believe themselves to be above it, and who feel an entitlement to exploit that for their own aims.

Added 21/06/2021: Today I again came across a statement that I thought worth mentioning, from the Explanatory Notes for the Data Protection Bill from 2017:

“Accordingly, Parliament passed the Data Protection Act 1984 and ratified the Convention in 1985, partly to ensure the free movement of data. The Data Protection Act 1984 contained principles which were taken almost directly from Convention 108 – including that personal data shall be obtained and processed fairly and lawfully and held only for specified purposes.”

“The Data Protection Directive (95/46/EC) (“the 1995 Directive”) provides the current basis for the UK’s data protection regime. The 1995 Directive stemmed from the European Commission’s concern that a number of Member States had not introduced national law related to Convention 108 which led to concern that barriers may be erected to data flows. In addition, there was a considerable divergence in the data protection laws between Member States. The focus of the 1995 Directive was to protect the right to privacy with respect to the processing of personal data and to ensure the free flow of personal data between Member States. “