At the CRISP hosted, Rise of Safety Tech, event this week, the moderator asked an important question: What is Safety Tech? Very honestly Graham Francis of the DCMS answered among other things, “It’s an answer we are still finding a question to.”

From ISP level to individual users, limitations to mobile phone battery power and app size compatibility, a variety of aspects within a range of technology were discussed. There is a wide range of technology across this conflated set of products packaged under the same umbrella term. Each can be very different from the other, even within one set of similar applications, such as school Safety Tech.

It worries me greatly that in parallel to the run up to the Online Harms legislation that their promotion appears to have assumed the character of a done deal. Some of these tools are toxic to children’s rights because of the policy that underpins them. Legislation should not be gearing up to make the unlawful lawful, but fix what is broken.

The current drive is towards the normalisation of the adoption of such products in the UK, and to make them routine. It contrasts with the direction of travel of critical discussion outside the UK.

Some Safety Tech companies have human staff reading flagged content and making decisions on it, while others claim to use only AI. Both might be subject to any future EU AI Regulation for example.

In the U.S. they also come under more critical scrutiny. “None of these things are actually built to increase student safety, they’re theater,” Lindsay Oliver, project manager for the Electronic Frontier Foundation was quoted as saying in an article just this week.

Here in the U.K. their regulatory oversight is not only startlingly absent, but the government is becoming deeply invested in cultivating the sector’s growth.

The big questions include who watches the watchers, with what scrutiny and safeguards? Is it safe, lawful, ethical, and does it work?

Safety Tech isn’t only an answer we are still finding a question to. It is a world view, with a particular value set. Perhaps the only lens through which its advocates believe the world wide web should be seen, not only by children, but by anyone. And one that the DCMS is determined to promote with “the UK as a world-leader” in a worldwide export market.

As an example one of the companies the DCMS champions in its May 2020 report, ‘‘Safer technology, safer users” claims to export globally already. “eSafe Global is now providing a service to about 1 million students and schools throughout the UK, UAE, Singapore, Malaysia and has been used in schools in Australia since 2011.“

But does the Department understand what they are promoting? The DCMS Minister responsible, Oliver Dowden said in Parliament on December 15th 2020: “Clearly, if it was up to individuals within those companies to identify content on private channels, that would not be acceptable—that would be a clear breach of privacy.”

He’s right. It is. And yet he and his Department are promoting it.

So how is this going to play out if at all, in the Online Harms legislation expected soon, that he owns together with the Home Office? Sadly the needed level of understanding by the Minister or in the third sector and much of the policy debate in the media, is not only missing, but is actively suppressed by the moral panic whipped up in emotive personal stories around a Duty of Care and social media platforms. Discussion is siloed about identifying CSAM, or grooming, or bullying or self harm, and actively ignores the joined-up, wider context within which Safety Tech operates.

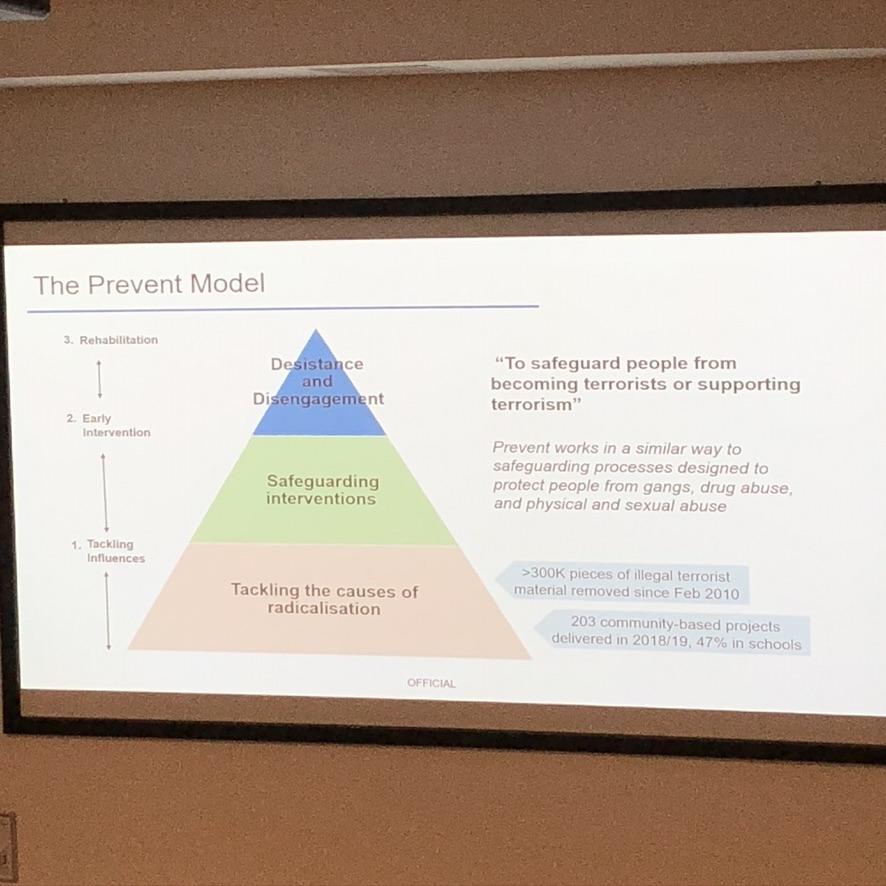

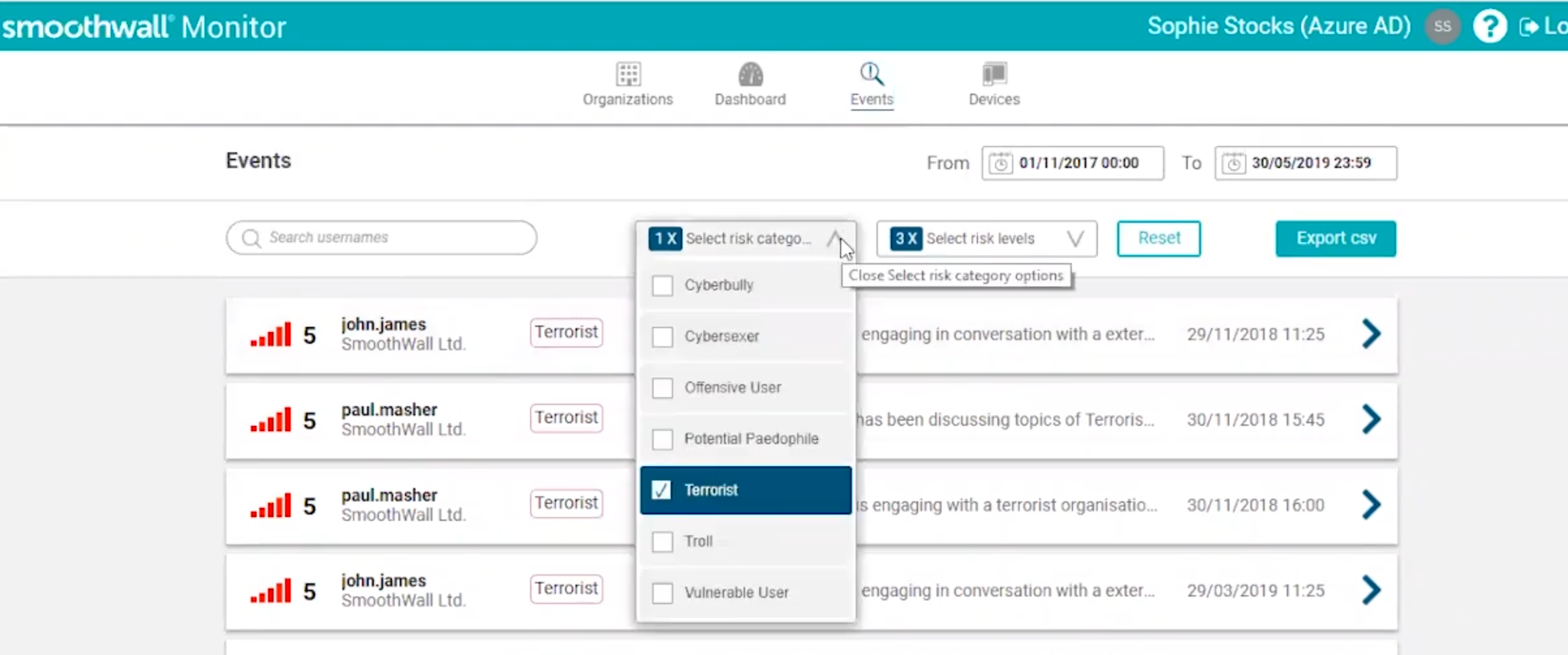

That context is the world of the Home Office. Of anti-terrorism efforts. Of mass surveillance and efforts to undermine encryption that are as nearly old as the Internet. The efforts to combat CSAM or child grooming online, operate in the same space. WePROTECT for example, sits squarely amid it all, established in 2014 by the UK Government and the then UK Prime Minister, David Cameron. Scrutiny of UK breaches of human rights law are well documented in ECHR rulings. Other state members of the alliance including the UAE stand accused of buying spyware to breach activists’ encrypted communications. It is disingenuous for any school Safety Tech actors to talk only of child protection without mention of this context. School Safety Tech while all different, operate by tagging digital activity with categories of risk, and these tags can include terrorism and extremism.

Once upon a time, school filtering and blocking services meant only denying access to online content that had no place in the classroom. Now it can mean monitoring all the digital activity of individuals, online and offline, using school or personal devices, working around encryption, whenever connected to the school network. And it’s not all about in-school activity. No matter where a child’s account is connected to the school network, or who is actually using it, their activity might be monitored 24/7, 365 days a year. A user’s activity that matches with the thousands of words or phrases on watchlists and in keyword libraries gets logged, and profiles individuals with ‘vulnerable’ behaviour tags, sometimes creating alerts. Their scope has crept from flagging up content, to flagging up children. Some schools create permanent records including false positives because they retain everything in a risk-averse environment, even things typed that a child subsequently deleted, and may be distributed and accessible by an indefinite number of school IT staff and stored in further third parties’ systems like CPOMS or Capita SIMS.

A wide range of the rights of the child are breached by mass monitoring in the UK, such as outlined in the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child General Comment No.25 which states that, “Any digital surveillance of children, together with any associated automated processing of personal data, should respect the child’s right to privacy and should not be conducted routinely, indiscriminately or without the child’s knowledge or, in the case of very young children, that of their parent or caregiver; nor should it take place without the right to object to such surveillance, in commercial settings and educational and care settings, and consideration should always be given to the least privacy-intrusive means available to fulfil the desired purpose.” (para 75)

Even the NSPCC, despite their recent public policy that opposes secure messaging using end-to-send encryption, recognises on its own Childline webpage the risk for children from content monitoring of children’s digital spaces, and that such monitoring may make them less safe.

In my work in 2018, one school Safety Tech company accepted our objections from defenddigitalme, that this monitoring went too far in its breach of children’s confidentially and safe spaces, and it agreed to stop monitoring counselling services. But there are roughly fifteen active companies here in the UK and the data protection regulator, the ICO despite being publicly so keen to be seen to protect children’s rights, has declined to act to protect children from the breach of their privacy and data protection rights across this field.

There are questions that should be straightforward to ask and answer, and while some CEOs are more willing to engage constructively with criticism and ideas for change than others, there is reluctance to address the key question: what is the lawful basis for monitoring children in school, at home, in- or out-side school hours?

Another important question often without an answer, is how do these companies train their algorithms whether in age verification or child safety tech? How accurate are the language inferences for an AI designed to catch children out who are being deceitful and where are assumptions, machine or man-made, wrong or discriminatory? It is overdue that our Regulator, the ICO, should do what the FTC did with Paravision, and require companies that develop tools through unlawful data processing to delete the output from it, the trained algorithm, plus products created from it.

Many of the harms from profiling children were recognised by the ICO in the Met Police gangs matrix: discrimination, conflation of victim and perpetrator, notions of ‘pre-crime’ without independent oversight, data distributed out of context, and excessive retention.

Harm is after all why profiling of children should be prohibited. And where, in exceptional circumstances, States may lift this restriction, it is conditional that appropriate safeguards are provided for by law.

While I believe any of the Safety Tech generated category profiles could be harmful to a child through mis-interventions, being treated differently by staff as a result, or harm a trusted relationship, perhaps the potentially most devastating to a child’s prospects are from mistakes that could be made under the Prevent duty.

The UK Home Office has pushed its Prevent agenda through schools since 2015, and it has been built into school Safety Tech by-design. School Safety Tech while all different, operate by tagging digital activity with categories of risk, and these tags can include terrorism and extremism. I know of schools that have flags attached to children’s records that are terrorism related, but who have had no Prevent referral. But there is no transparency of these numbers at all. There is no oversight to ensure children do not stay wrongly tagged with those labels. Families may never know.

Perhaps the DCMS needs to ask itself, are the values of the UK Home Office really what the UK should export to children globally from “the UK as a world-leader” without independent legal analysis, without safeguards, and without taking accountability for their effects?

The Home Office values are demonstrated in its approach to the life and death of migrants at sea, children with no recourse to public funds, to discriminatory stop and search, a Department that doesn’t care enough to even understand or publish the impact of its interventions on children and their families.

The Home Office talk is of safeguarding children, but it is opposed to them having safe spaces online. School Safety Tech tools actively work around children’s digital security, can act as a man-in-the-middle, and can create new risks. There is no evidence I have seen that on balance convinces me that school Safety Tech does in fact make children safer. But plenty of evidence that the Home Office appears to want to create the conditions that make children less secure so that such tools could thrive, by weakening the security of digital activity through its assault on end-to-end encryption. My question is whether Online Harms is to be the excuse to give it a lawful basis.

Today there are zero statutory transparency obligations, testing or safety standards required of school Safety Tech before it can be procured in UK state education at scale.

So what would a safe and lawful framework for operation look like? It would be open to scrutiny and require regulatory action, and law.

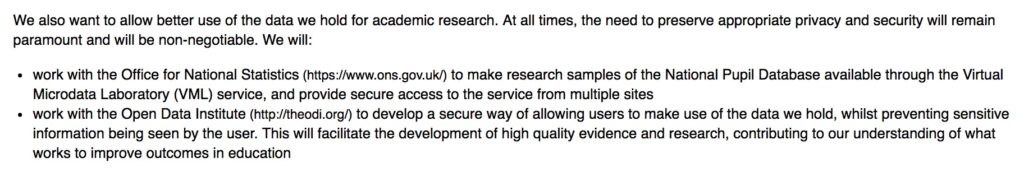

There are no published numbers of how many records are created about how many school children each year. There are no safeguards in place to protect children’s rights or protection from harm in terms of false positives, error retention, transfer of records to the U.S. or third party companies, or how many covert photos they have enabled to be taken of children via webcam by school staff. There is no equivalent of medical device ‘foreseeable misuse risk assessment’ such as ISO 14971 would require, despite systems being used for mental health monitoring with suicide risk flags. Children need to know what is on their record and to be able to seek redress when it is wrong. The law would set boundaries and safeguards and both existing and future law would need to be enforced. And we need independent research on the effects of school surveillance, and its chilling effects on the mental health and behaviour of developing young people.

Companies may argue they are transparent, and seek to prove how accurate their tools are. Perhaps they may become highly accurate.

But no one is yet willing to say in the school Safety Tech sector, these are thousands of words that if your child types may trigger a flag, or indeed, here’s an annual report of all the triggered flags and your own or your child’s saved profile. A school’s interactions with children’s social care already offers a framework for dealing with information that could put a child at risk from family members, so reporting should be do-able.

At the end of the event this week, the CRISP event moderator said of their own work, outside schools, that, “we are infiltrating bad actor networks across the globe and we are looking at everything they are saying. […] We have a viewpoint that there are certain lines where privacy doesn’t exist anymore.”

Their company website says their work involves, “uncovering and predicting the actions of bad actor, activist, agenda-driven and interest groups“. That’s a pretty broad conflation right there. Their case studies include countering social media activism against a luxury apparel brand. And their legal basis of ‘legitimate interests‘ for their data processing might seem flimsy at best, for such a wide ranging surveillance activity where, ‘privacy doesn’t exist anymore’.

I must often remind myself that the people behind Safety Tech may epitomise the very best of what some believe is making the world safer online as they see it. But it is *as they see it*. And if policy makers or CEOs have convinced themselves that because ‘we are doing it for good, a social impact, or to safeguard children’, that breaking the law is OK, then it should be a red flag that these self-appointed ‘good guys’ appear to think themselves above the law.

My takeaway time and time again, is that companies alongside governments, policy makers, and a range of lobbying interests globally, want to redraw the lines around human rights, so that they can overstep them. There are “certain lines” that don’t suit their own business models or agenda. The DCMS may talk about seeing its first safety tech unicorn, but not about the private equity funding, or where they pay their taxes. Children may be the only thing they talk about protecting but they never talk of protecting children’s rights.

In the school Safety Tech sector, there is activity that I believe is unsafe, or unethical, or unlawful. There is no appetite or motivation so far to fix it. If in upcoming Online Harms legislation the government seeks to make lawful what is unlawful today, I wonder who will be held accountable for the unsafe and the unethical, that come with the package deal—and will the Minister run that reputational risk?