Today was the APPG AI Evidence Meeting – The National AI Strategy: How should it look? Here’s some of my personal views and takeaways.

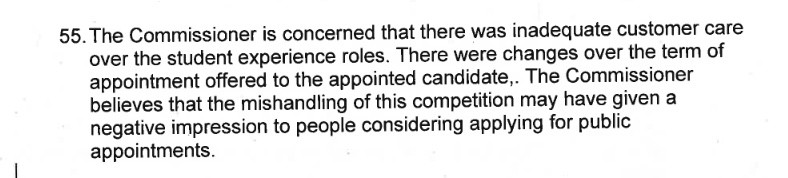

Have the Regulators the skills and competency to hold organisations to account for what they are doing? asked Roger Taylor, the former Chair of Ofqual the exams regulator, as he began the panel discussion, chaired by Lord Clement-Jones.

A good question was followed by another.

What are we trying to do with AI? asked Andrew Strait, Associate Director of Research Partnerships at Ada Lovelace Institute and formerly of DeepMind and Google. The goal of a strategy should not be to have more AI for the sake of having more AI, he said, but an articulation of values and goals. (I’d suggest the government may be in fact in favour of exactly that, more AI for its own sake where its appplication is seen as a growth market.) And interestingly he suggested that the Scottish strategy has more values-based model, such as fairness. [I had, it seems, wrongly assumed that a *national* AI strategy to come, would include all of the UK.]

The arguments on fairness are well worn in AI discussion and getting old. And yet they still too often fail to ask whether these tools are accurate or even work at all. Look at the education sector and one company’s product, ClassCharts, that claimed AI as its USP for years, but the ICO found in 2020 that the company didn’t actually use any AI at all. If company claims are not honest, or not accurate, then they’re not fair to anyone, never mind across everyone.

Fairness is still too often thought of in terms of explainability of a computer algorithm, not the entire process it operates in. As I wrote back in 2019, “yes we need fairness accountability and transparency. But we need those human qualities to reach across thinking beyond computer code. We need to restore humanity to automated systems and it has to be re-instated across whole processes.”

Strait went on to say that safe and effective AI would be something people can trust. And he asked the important question: who gets to define what a harm is? Rightly identifying that the harm identified by a developer of a tool, may be very different from those people affected by it. (No one on the panel attempted to define or limit what AI is, in these discussions.) He suggested that the carbon footprint from AI may counteract the benefit it would have to apply AI in the pursuit of climate-change goals. “The world we want to create with AI” was a very interesting position and I’d have liked to hear him address what he meant by that, who is “we”, and any assumptions within it.

Lord Clement-Jones asked him about some of the work that Ada Lovelace had done on harms such as facial recognition, and also asked whether some sector technologies are so high risk that they must be regulated? Strait suggested that we lack adequate understanding of what harms are — I’d suggest academia and civil society have done plenty of work on identifying those, they’ve just been too often ignored until after the harm is done and there are legal challenges. Strait also suggested he thought the Online Harms agenda was ‘a fantastic example’ of both horizontal and vertical regulation. [Hmm, let’s see. Many people would contest that, and we’ll see what the Queen’s Speech brings.]

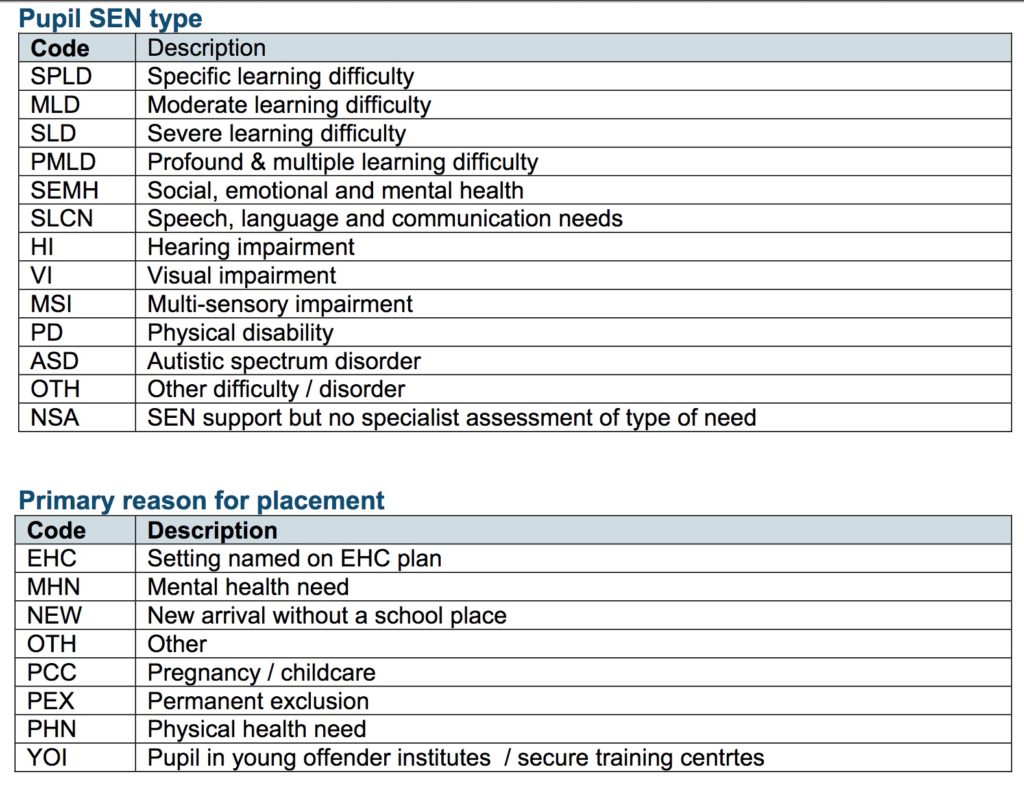

Maria Axente then went on to talk about children and AI. Her focus was on big platforms but also mentioned a range of other application areas. She spoke of the data governance work going on at UNICEF. She included the needs for driving awareness of the risks for children and AI, and digital literacy. The potential for limitations on child development, the exacerbation of the digital divide, and risks in public spaces but also hoped for opportunities. She suggested that the AI strategy may therefore be the place for including children.

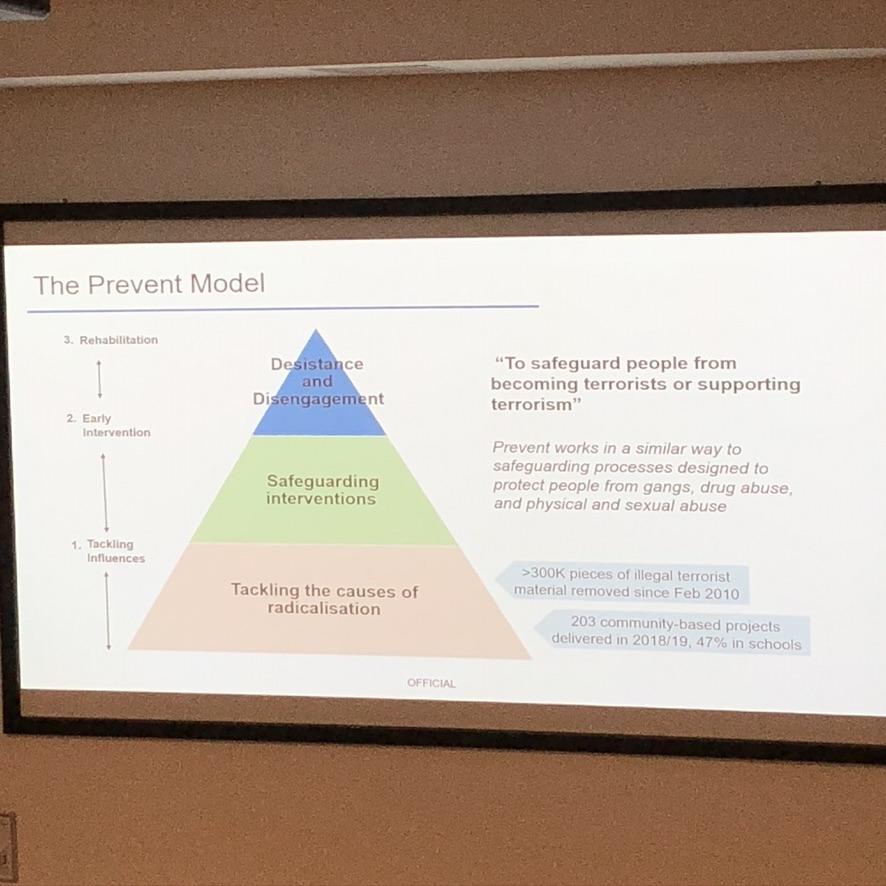

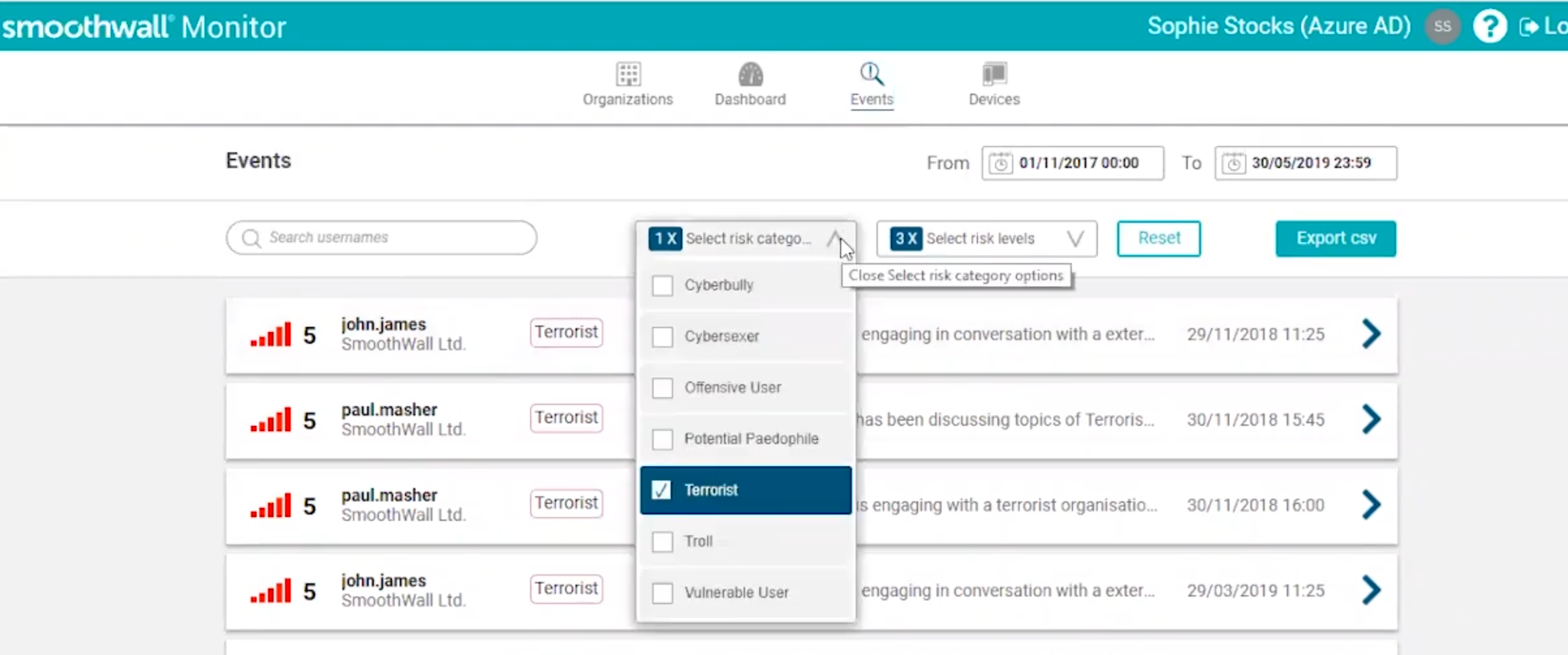

This of course was something I would want to discuss at more length, but in summary the last decade of Westminster policy affecting children, even the Children’s Commissioner most recent Big Ask survey, bypass the question of children’s *rights* completely. If the national AI strategy by contrast would address rights, [the foundation upon which data laws are built] and create the mechanisms in public sector interactions with children that would enable them to be told if and how their data is being used (in AI systems or otherwise) and be able to exercise the choices that public engagement time and time again says is what people want, then that would be a *huge* and positive step forward to effective data practice across the public sector and for use of AI. Otherwise I see a risk that a strategy on AI and children will ignore children as rights holders across a full range of rights in the digital environment, and focus only on the role of AI in child protection, a key DCMS export aim, and ignore the invasive nature of safety tech tools, and its harms.

Next Dr Jim Weatherall from Astra Zeneca tied together leveraging “the UK unique strengths of the NHS” and “data collected there” wanting a close knitting together of the national AI strategy and the national data strategy, so that healthcare, life sciences and biomedical sector can become “an international renowned asset.” He’d like to see students doing data science modules in studies and international access to talent to work for AZ.

Lord Clement-Jones then asked him how to engender public trust in data use. Weatherall said a number of false starts in the past are hindering progress, but that he saw the way forward was data trusts and citizen juries.

His answer ignores the most obvious solution: respect existing law and human rights, using data only in ways that people want and give their permission to do so. Then show them that you did that, and nothing more. In short, what medConfidential first proposed in 2014, the creation of data usage reports.

The infrastructure for managing personal data controls in the public sector, as well as its private partners, must be the basic building block for any national AI strategy. Views from public engagement work, polls, and outreach has not changed significantly since those done in 2013-14, but ask for the same over and over again. Respect for ‘red lines’ and to have control and choice. Won’t government please make it happen?

If the government fails to put in place those foundations, whatever strategy it builds will fall in the same ways they have done to date, like care.data did by assuming it was acceptable to use data in the way that the government wanted, without a social licence, in the name of “innovation”. Aims that were championed by companies such as Dr Foster, that profited from reusing personal data from the public sector, in a “hole and corner deal” as described by the chairman of the House of Commons committee of public accounts in 2006. Such deals put industry and “innovation” ahead of what the public want in terms of ‘red lines’ for acceptable re-uses of their own personal data and for data re-used in the public interest vs for commercial profit. And “The Department of Health failed in its duty to be open to parliament and the taxpayer.” That openness and accountability are still missing nearly ten years on in the scope creep of national datasets and commercial reuse, and in expanding data policies and research programmes.

I disagree with the suggestion made that Data Trusts will somehow be more empowering to everyone than mechanisms we have today for data management. I believe Data Trusts will further stratify those who are included and those excluded, and benefit those who have capacity to be able to participate, and disadvantage those who cannot choose. They are also a figleaf of acceptability that don’t solve the core challenge . Citizen juries cannot do more than give a straw poll. Every person whose data is used has entitlement to rights in law, and the views of a jury or Trust cannot speak for everyone or override those rights protected in law.

Tabitha Goldstaub spoke next and outlined some of what AI Council Roadmap had published. She suggested looking at removing barriers to best support the AI start-up community.

As I wrote when the roadmap report was published, there are basics missing in government’s own practice that could be solved. It had an ambition to, “Lead the development of data governance options and its uses. The UK should lead in developing appropriate standards to frame the future governance of data,” but the Roadmap largely ignored the governance infrastructures that already exist. One can only read into that a desire to change and redesign what those standards are.

I believe that there should be no need to change the governance of data but instead make today’s rights able to be exercised and deliver enforcement to make existing governance actionable. Any genuine “barriers” to data use in data protection law, are designed as protections for people; the people the public sector, its staff and these arms length bodies are supposed to serve.

Blaming AI and algorithms, blaming lack of clarity in the law, blaming “barriers” is often avoidance of one thing. Human accountability. Accountability for ignorance of the law or lack of consistent application. Accountability for bad policy, bad data and bad applications of tools is a human responsibility. Systems you choose to apply to human lives affect people, sometimes forever and in the most harmful ways, so those human decisions must be accountable.

I believe that some simple changes in practice when it comes to public administrative data could bring huge steps forward there:

- An audit of existing public admin data held, by national and local government, and consistent published registers of databases and algorithms / AI / ML currently in use.

- Identify the lawful basis for each set of data processes, their earliest records dates and content.

- Publish that resulting ROPA and storage limitations.

- Assign accountable owners to databases, tools and the registers.

- Sort out how you will communicate with people whose data you unlawfully process to meet the law, or stop processing it.

- And above all, publish a timeline for data quality processes and show that you understand how the degradation of data accuracy, quality affect the rights and responsibilities in law that change over time, as a result.

Goldstaub went on to say on ethics and inclusion, that if it’s not diverse, it’s not ethical. Perhaps the next panel itself and similar events could take a lesson learned from that, as such APPG panel events are not as diverse as they could or should be themselves. Some of the biggest harms in the use of AI are after all for those in communities least represented, and panels like this tend to ignore lived reality.

The Rt Rev Croft then wrapped up the introductory talks on that more human note, and by exploding some myths. He importantly talked about the consequences he expects of the increasing use of AI and its deployment in ‘the future of work’ for example, and its effects for our humanity. He proposed 5 topics for inclusion in the strategy and suggested it is essential to engage a wide cross section of society. And most importantly to ask, what is this doing to us as people?

There were then some of the usual audience questions asked on AI, transparency, garbage-in garbage-out, challenges of high risk assessment, and agreements or opposition to the EU AI regulation.

What frustrates me most in these discussions is that the technology is an assumed given, and the bias that gives to the discussion, is itself ignored. A holistic national AI strategy should be looking at if and why AI at all. What are the consequences of this focus on AI and what policy-making-oxygen and capacity does it take away from other areas of what government could or should be doing? The questioner who asks how adaptive learning could use AI for better learning in education, fails to ask what does good learning look like, and if and how adaptive tools fit into that, analogue or digital, at all.

I would have liked to ask panelists if they agree that proposals of public engagement and digital literacy distract from lack of human accountability for bad policy decisions that use machine-made support? Taking examples from 2020 alone, there were three applications of algorithms and data in the public sector challenged by civil society because of their harms: from the Home Office dropping its racist visa algorithm, DWP court case finding ‘irrational and unlawful’ in Universal Credit decisions, and the “mutant algorithm” of summer 2020 exams. Digital literacy does nothing to help people in those situations. What AI has done is to increase the speed and scale of the harms caused by harmful policy, such as the ‘Hostile Environment’ which is harmful by design.

Any Roadmap, AI Council recommendations, and any national strategy if serious about what good looks like, must answer how would those harms be prevented in the public sector *before* being applied. It’s not about the tech, AI or not, but misuse of power. If the strategy or a Roadmap or ethics code fails to state how it would prevent such harms, then it isn’t serious about ethics in AI, but ethics washing its aims under the guise of saying the right thing.

One unspoken problem right now is the focus on the strategy solely for the delivery of a pre-determined tool (AI). Who cares what the tool is? Public sector data comes from the relationship between people and the provision of public services by government at various levels, and its AI strategy seems to have lost sight of that.

What good would look like in five years would be the end of siloed AI discussion as if it is a desirable silver bullet, and mythical numbers of ‘economic growth’ as a result, but see AI treated as is any other tech and its role in end-to-end processes or service delivery would be discussed proportionately. Panelists would stop suggesting that the GDPR is hard to understand or people cannot apply it. Almost all of the same principles in UK data laws have applied for over twenty years. And regardless of the GDPR, the Convention 108 applies to the UK post-Brexit unchanged, including associated Council of Europe Guidelines on AI, data protection, privacy and profiling.

Data laws. AI regulation. Profiling. Codes of Practice on children, online safety or biometrics and emotional or gait recognition. There *are* gaps in data protection law when it comes to biometric data not used for unique identification purposes. But much of this is already rolled into other law and regulation for the purposes of upholding human rights and the rule of law. The challenge in the UK is often not having the law, but its lack of enforcement. There are concerns in civil society that the DCMS is seeking to weaken core ICO duties even further. Recent government, council and think tank roadmaps talk of the UK leading on new data governance, but in reality simply want to see established laws rewritten to be less favourable of rights. To be less favourable towards people.

Data laws are *human* rights-based laws. We will never get a workable UK national data strategy or national AI strategy if government continues to ignore the very fabric of what they are to be built on. Policy failures will be repeated over and over until a strategy supports people to exercise their rights and have them respected.

Imagine if the next APPG on AI asked what would human rights’ respecting practice and policy look like, and what infrastructure would the government need to fund or build to make it happen? In public-private sector areas (like edTech). Or in the justice system, health, welfare, children’s social care. What could that Roadmap look like and how we can make it happen over what timeframe? Strategies that could win public trust *and* get the sectoral wins the government and industry are looking for. Then we might actually move forwards on getting a functional strategy that would work, for delivering public services and where both AI and data fit into that.