Since it appears that the Independent Commission on Freedom of Information [FOI] has not published all of the received submissions, I thought I’d post what I’d provided via email.

I’d answered two of the questions with two case studies. The first on application of section 35 and 36 exemptions and the safe space. The second on the proposal for potential charges.

On the Commission website, the excel spreadsheet of evidence submitted online, tab 2 notes that NHS England asked belatedly for its submission be unpublished.

I wonder why.

Follow up to both these FOI requests are now long overdue in 2016. The first from NHS England for the care.data decision making behind the 2015 decision not to publish a record of whether part of the board meetings were to be secret. Transparency needs to be seen in action, to engender public trust. After all, they’re deciding things like how care.data and genomics will be at the “heart of the transformation of the NHS.”

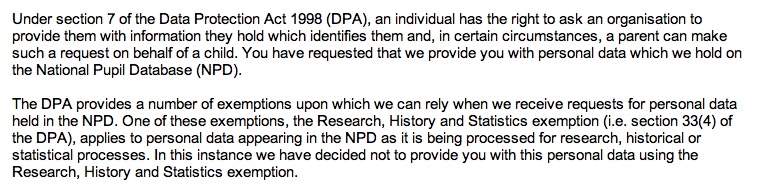

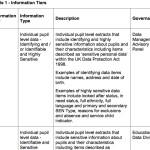

The second is overdue at the Department for Education on the legal basis for identifiable sensitive data releases from the National Pupil Database that meets Schedule 3 of the Data Protection Act 1998 to permit this datasharing with commercial third parties.

Both in line with the apparently recommended use of FOI

according to Mr. Grayling who most recently said:

“It is a legitimate and important tool for those who want to understand why and how Government is taking decisions and it is not the intention of this Government to change that”. [Press Gazette]

We’ll look forward to see whether that final sentence is indeed true.

*******

Independent Commission on Freedom of Information Submission

Question 1: a) What protection should there be for information relating to the internal deliberations of public bodies? b) For how long after a decision does such information remain sensitive? c) Should different protections apply to different kinds of information that are currently protected by sections 35 and 36?

A “safe space” in which to develop and discuss policy proposals is necessary. I can demonstrate where it was [eventually] used well, in a case study of a request I made to NHS England. [1]

The current protection afforded to the internal deliberations of public bodies are sufficient given section 35 and 36 exemptions. I asked in October 2014 for NHS England to publish the care.data planning and decision making for the national NHS patient data extraction programme. This programme has been controversial [2]. It will come at great public expense and to date has been harmful to public and professional trust with no public benefit. [3]

NHS England refused my request based on Section 22 [intended for future publication]. [4] However ten months later the meeting minutes had never been published. In July 2015, after appeal, the Information Commissioner issued an Information Notice and NHS England published sixty-three minutes and papers in August 2015.

In these released documents section 36 exemption was then applied to only a tiny handful of redacted comments. This was sufficient to protect the decisions that NHS England had felt to be most sensitive and yet still enable the release of a year’s worth of minutes.

Transparency does not mean that difficult decisions cannot be debated since only outcomes and decisions are recorded, not every part of every discussion verbatim.

The current provision for safe space using these exemptions is effective and in this case would have been no different made immediately after the meeting or one and a half years later. If anything, publication sooner may have resulted in better informed policy and decision making through wider involvement from professionals and civil society. The secrecy in the decision making did not build trust.

When policies such as these are found to have no financial business cost-benefit case for example, I believe it is strongly in the public interest to have transparency of these facts, to scrutinise the policy governance in the public interest to enable early intervention when seen to be necessary.

In the words of the Information Commissioner:

“FOIA can rightly challenge and pose awkward questions to public authorities. That is part of democracy. However, checks and balances are needed to ensure that the challenges are proportionate when viewed against all the other vital things a public authority has to do.

“The Commissioner believes that the current checks and balances in the legislation are sufficient to achieve this outcome.” [5]

Given that most public bodies, including NHS England’s Board, routinely publish its minutes this would seem a standard good practice to be expected and I believe routine publication of meeting minutes would have raised trustworthiness of the programme and its oversight and leadership.

The same section 36 exemption could have been applied from the start to the small redactions that were felt necessary balanced against the public interest of open and transparent decision making.

I do not believe more restrictive applications should be made than are currently under sections 35 and 36.

_____________________________________________________________________

Question 6: Is the burden imposed on public authorities under the Act justified by the public interest in the public’s right to know? Or are controls needed to reduce the burden of FoI on public authorities?

As an individual I made 40 requests of schools and 2 from the Department for Education which may now result in benefit for 8 million children and their families, as well as future citizens.

The transparency achieved through these Freedom of Information requests will I hope soon transform the culture at the the Department for Education from one of secrecy to one of openness.

There is the suggestion that a Freedom of Information request would incur a charge to the applicant.

I believe that the benefits of the FOI Act in the public interest outweigh the cost of FOI to public authorities. In this second example [6], I would ask the Commission to consider if I had not been able to make these Freedom of Information requests due to cost, and therefore I was not able to present evidence to the Minister, Department, and the Information Commissioner, would the panel members support the secrecy around the ongoing risk that current practices pose to children and our future citizens?

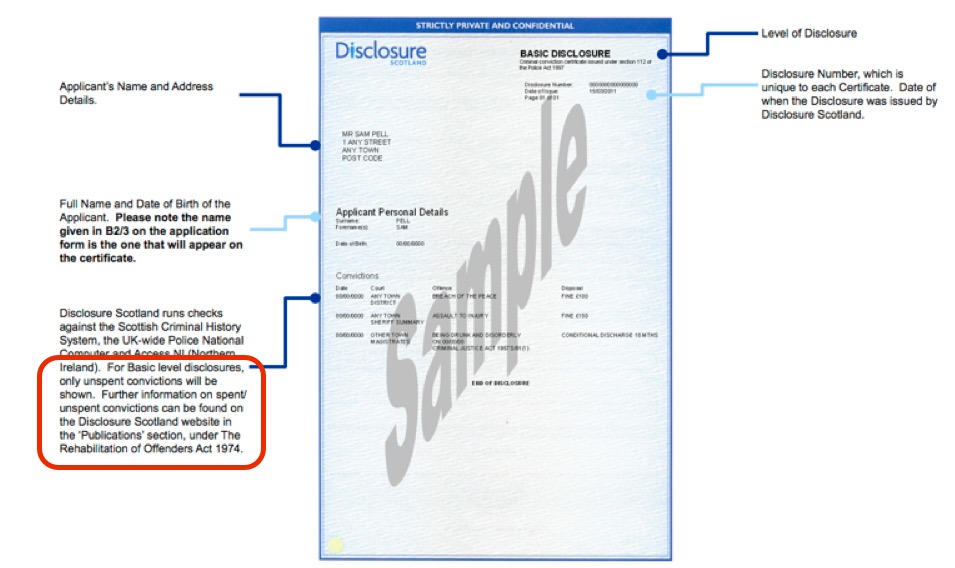

Individual, identifiable and sensitive pupil data are released to third parties from the National Pupil Database without telling pupils, parents and schools or their consent. This Department for Education (DfE) FOI request aimed to obtain understanding of any due diligence and the release process: privacy impact and DfE decision making, with a focus on its accountability.

This was to enable transparency and scrutiny in the public interest, to increase the understanding of how our nation’s children’s personal data are used by government, commercial third parties, and even identifiable and sensitive data given to members of the press.

Chancellor Mr. Osborne spoke on November 17 about the importance of online data protection:

“Each of these attacks damages companies, their customers, and the public’s trust in our collective ability to keep their data and privacy safe.”[…] “Imagine the cumulative impact of repeated catastrophic breaches, eroding that basic faith… needed for our online economy & social life to function.”

Free access to FOI enabled me as a member of the public to ask and take action with government and get information from schools to improve practices in the broad public interest.

If there was a cost to this process I could not afford to ask schools to respond. Schools are managed individually, and as such I requested the answer to the question; whether they were aware of the National Pupil Database and how the Department shared their pupils’ data onwardly with third parties.

I asked a range of schools in the South and East. In order to give a fair picture of more than one county I made requests from a range of types of school – from academy trusts to voluntary controlled schools – 20 primary and 20 secondary. Due to the range of schools in England and Wales [7] this was a small sample.

Building even a small representative picture of pupil data privacy arrangements in the school system therefore required a separate request to each school.

I would not have been able to do this, had there been a charge imposed for each request. This research subsequently led me to write to the Information Commissioner’s Office, with my findings.

Were this only to be a process that access costs would mean organisations or press could enter into due to affordability, then the public would only be able to find out what matters or was felt important to those organisations, but not what matters to individuals.

However what matters to one individual might end up making a big difference to many people.

Individuals may be interested in what are seen as minority topics, perhaps related to discrimination according to gender, sexuality, age, disability, class, race or ethnicity. If individuals cannot afford to challenge government policies that matter to them as an individual, we may lose the benefit that they can bring when they go on to champion the rights of more people in the country as a whole.

Eight million children’s records, from children aged 2-19 are stored in the National Pupil Database. I hope that due to the FOI request increased transparency and better practices will help restore their data protections for individuals and also re-establish organisational trust in the Department.

Information can be used to enable or constrain citizenship. In order to achieve universal access to human rights to support participation, transparency and accountability, I appeal that the Commission recognise the need for individuals to tackle vested interests, unjust laws and policies.

Any additional barriers such as cost, only serve to reduce equality and make society less just. There is however an immense intangible value in an engaged public which is hard to measure. People are more likely to be supportive of public servant decision making if they are not excluded from it.

Women for example are underrepresented in Parliament and therefore in public decision making. Further, the average gap within the EU pay is 16 per cent, but pay levels throughout the whole of Europe differ hugely, and in the South East of the UK men earn 25 per cent more than their female counterparts. [8] Women and mothers like me may therefore find it more difficult to participate in public life and to make improvements on behalf of other families and children across the country.

To charge for access to information about our public decision making process could therefore be excluding and discriminatory.

I believe these two case studies show that the Act’s intended objectives, on parliamentary introduction — to ‘transform the culture of Government from one of secrecy to one of openness’; ‘raise confidence in the processes of government, and enhance the quality of decision making by Government’; and to ‘secure a balance between the right to information…and the need for any organisation, including Government, to be able to formulate its collective policies in private’ — work in practice.

If anything, they need strengthened to ensure accessibility.

Any actions to curtail free and equal access to these kinds of information would not be in the public interest and a significant threat to the equality of opportunity offered to the public in making requests. Charging would particularly restrict access to FOI for poorer individuals and communities who are often those already excluded from full public participation in public life.

___________________________________________________________________________

[1] https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/caredata_programme_board_minutes

[2] http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/dec/12/nhs-patient-care-data-sharing-scheme-delayed-2015-concerns

[3] http://www.statslife.org.uk/news/1672-new-rss-research-finds-data-trust-deficit-with-lessons-for-policymakers

[4] https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/caredataprogramme_FOI.pdf

[5] https://ico.org.uk/media/about-the-ico/consultation-responses/2015/1560175/ico-response-independent-commission-on-freedom-of-information.pdf

[6] https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/NPD_FOI_submissionv3.pdf

[7] http://www.newschoolsnetwork.org/sites/default/files/Comparison%20of%20school%20types.pdf

[8] http://www.equalpayportal.co.uk/statistics/