Five years ago, researchers at the Manchester University School of Social Sciences wrote, “It will no longer be possible to assume that secondary data use is ethically unproblematic.”

Five years on, other people’s use of the language of data ethics puts social science at risk. Event after event, we are witnessing the gradual dissolution of the value and meaning of ‘ethics’, into little more than a buzzword.

Companies and organisations are using the language of ‘ethical’ behaviour blended with ‘corporate responsibility’ modelled after their own values, as a way to present competitive advantage.

Ethics is becoming shorthand for, ‘we’re the good guys’. It is being subverted by personal data users’ self-interest. Not to address concerns over the effects of data processing on individuals or communities, but to justify doing it anyway.

An ethics race

There’s certainly a race on for who gets to define what data ethics will mean. We have at least three new UK institutes competing for a voice in the space. Digital Catapult has formed an AI ethics committee. Data charities abound. Even Google has developed an ethical AI strategy of its own, in the wake of their Project Maven.

Lessons learned in public data policy should be clear by now. There should be no surprises how administrative data about us are used by others. We should expect fairness. Yet these basics still seem hard for some to accept.

The NHS Royal Free Hospital in 2015 was rightly criticised – because they tried “to commercialise personal confidentiality without personal consent,” as reported in Wired recently.

“The shortcomings we found were avoidable,” wrote Elizabeth Denham in 2017 when the ICO found six ways the Google DeepMind — Royal Free deal did not comply with the Data Protection Act. The price of innovation, she said, didn’t need to be the erosion of fundamental privacy rights underpinned by the law.

If the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation is put on a statutory footing where does that leave the ICO, when their views differ?

It’s why the idea of DeepMind funding work in Ethics and Society seems incongruous to me. I wait to be proven wrong. In their own words, “technologists must take responsibility for the ethical and social impact of their work“. Breaking the law however, is conspicuous by its absence, and the Centre must not be used by companies, to generate pseudo lawful or ethical acceptability.

Do we need new digital ethics?

Admittedly, not all laws are good laws. But if recognising and acting under the authority of the rule-of-law is now an optional extra, it will undermine the ICO, sink public trust, and destroy any hope of achieving the research ambitions of UK social science.

I am not convinced there is any such thing as digital ethics. The claimed gap in an ability to get things right in this complex area, is too often after people simply get caught doing something wrong. Technologists abdicate accountability saying “we’re just developers,” and sociologists say, “we’re not tech people.”

These shrugs of the shoulders by third-parties, should not be rewarded with more data access, or new contracts. Get it wrong, get out of our data.

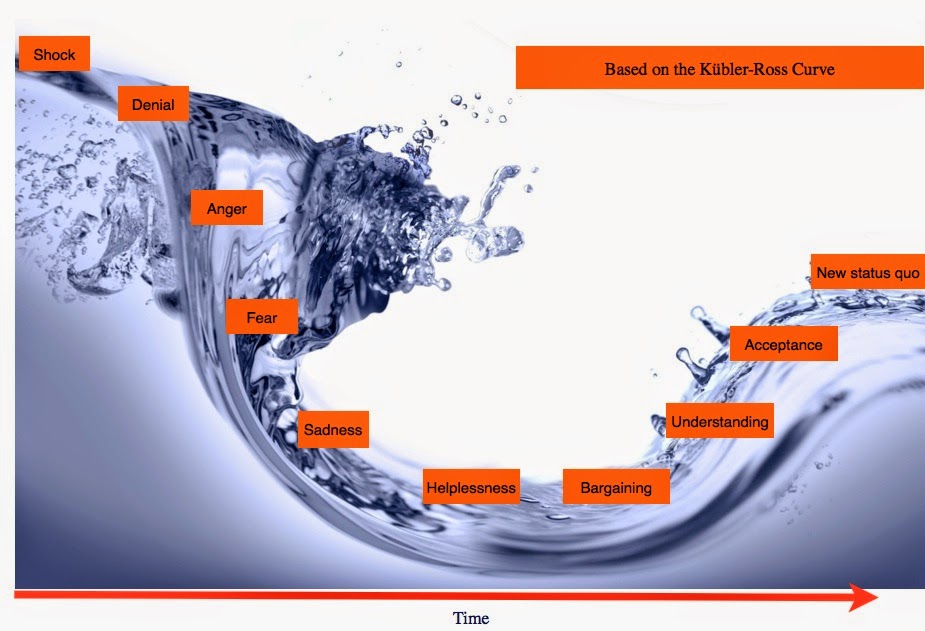

This lack of acceptance of responsibility creates a sense of helplessness. We can’t make it work, so let’s make the technology do more. But even the most transparent algorithms will never be accountable. People can be accountable, and it must be possible to hold leaders to account for the outcomes of their decisions.

But it shouldn’t be surprising no one wants to be held to account. The consequences of some of these data uses are catastrophic.

Accountability is the number one problem to be solved right now. It includes openness of data errors, uses, outcomes, and policy. Are commercial companies, with public sector contracts, checking data are accurate and corrected from people who the data are about, before applying in predictive tools?

Unethical practice

As Tim Harford in the FT once asked about Big Data uses in general: “Who cares about causation or sampling bias, though, when there is money to be made?”

Problem area number two, whether researchers are are working towards a profit model, or chasing grant funding is this:

How data users can make unbiased decisions whether they should use the data? We have all the same bodies deciding on data access, that oversee its governance. Conflict of self interest is built-in by default, and the allure of new data territory is tempting.

But perhaps the UK key public data ethics problem, is that the policy is currently too often about the system goal, not about improving the experience of the people using systems. Not using technology as a tool, as if people mattered. Harmful policy, can generate harmful data.

Secondary uses of data are intrinsically dependent on the ethics of the data’s operational purpose at collection. Damage-by-design is evident right now across a range of UK commercial and administrative systems. Metrics of policy success and associated data may be just wrong.

- System user needs of current DWP policy are prioritised above the human dignity of PIP claimants.

- Britain has long profiled black boys as criminals in the justice system, and predictive and increasingly linked data across services is worsening this, certainly in London.

- Common sense, and much more has gone wrong in Student Loans Company surveillance

- Home Office reviews wrongly identified students as potentially fraudulent, yet their TOIEC visa cancellations has irrevocably damaged lives without redress.

Some of the damage is done by collecting data for one purpose and using it operationally for another in secret. Until these modus operandi change no one should think that “data ethics will save us”.

Some of the most ethical research aims try to reveal these problems. But we need to also recognise not all research would be welcomed by the people the research is about, and few researchers want to talk about it. Among hundreds of already-approved university research ethics board applications I’ve read, some were desperately lacking. An organisation is no more ethical than the people who make decisions in its name. People disagree on what is morally right. People can game data input and outcomes and fail reproducibility. Markets and monopolies of power bias aims. Trying to support the next cohort of PhDs and impact for the REF, shapes priorities and values.

“Individuals turn into data, and data become regnant.” Data are often lacking in quality and completeness and given authority they do not deserve.

It is still rare to find informed discussion among the brightest and best of our leading data institutions, about the extensive everyday real world secondary data use across public authorities, including where that use may be unlawful and unethical, like buying from data brokers. Research users are pushing those boundaries for more and more without public debate. Who says what’s too far?

The only way is ethics? Where next?

The latest academic-commercial mash-ups on why we need new data ethics in a new regulatory landscape where the established is seen as past it, is a dangerous catch-all ‘get out of jail free card’.

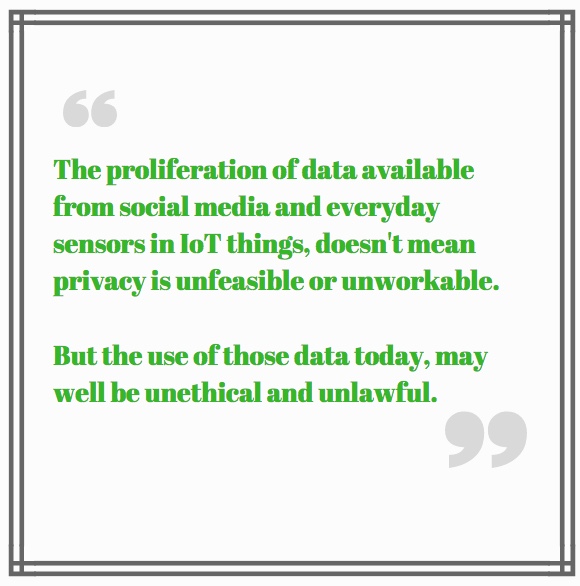

Ethical barriers are out of step with some of today’s data politics. The law is being sidestepped and regulation diminished by lack of enforcement of gratuitous data grabs from the Internet of Things, and social media data are seen as a free-for-all. Data access barriers are unwanted. What is left to prevent harm?

I’m certain that we first need to take a step back if we are to move forward. Ethical values are founded on human rights that existed before data protection law. Fundamental human decency, rights to privacy, and to freedom from interference, common law confidentiality, tort, and professional codes of conduct on conflict of interest, and confidentiality.

Data protection law emphasises data use. But too often its first principles of necessity and proportionality are ignored. Ethical practice would ask more often, should we collect the data at all?

Although GDPR requires new necessary safeguards to ensure that technical and organisational measures are met to control and process data, and there is a clearly defined Right to Object, I am yet to see a single event thought giving this any thought.

Let’s not pretend secondary use of data is unproblematic, while uses are decided in secret. Calls for a new infrastructure actually seek workarounds of regulation. And human rights are dismissed.

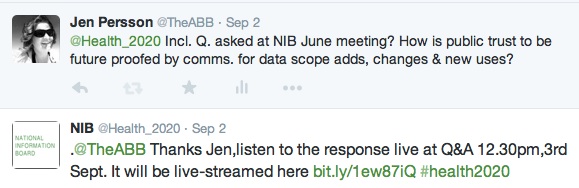

Building a social license between data subjects and data users is unavoidable if use of data about people hopes to be ethical.

The lasting solutions are underpinned by law, and ethics. Accountability for risk and harm. Put the person first in all things.

We need more than hopes and dreams and talk of ethics.

We need realism if we are to get a future UK data strategy that enables human flourishing, with public support.

Notes of desperation or exasperation are increasingly evident in discourse on data policy, and start to sound little better than ‘we want more data at all costs’. If so, the true costs would be lasting.

Perhaps then it is unsurprising that there are calls for a new infrastructure to make it happen, in the form of Data Trusts. Some thoughts on that follow too.

Part 1. Ethically problematic

Ethics is dissolving into little more than a buzzword. Can we find solutions underpinned by law, and ethics, and put the person first?

Part 2. Can Data Trusts be trustworthy?

As long as data users ignore data subjects rights, Data Trusts have no social license.

Data Horizons: New Forms of Data For Social Research,

![Building Public Trust in care.data datasharing [3]: three steps to begin to build trust](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/optout_ppt-672x372.jpg)

![Building Public Trust [2]: a detailed approach to understanding Public Trust in data sharing](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Trust-e1426443553441-672x372.jpg)