Recent conversations and the passage of the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill in parliament, have made me think once again about what the future vision for UK children’s data could be.

Some argue that processing and governance should be akin to a health model, first do no harm, professional standards, training, ISO lifecycle oversight, audits and governance bodies to approve exceptional releases and re-use.

Education data is health and body data

Children’s personal data in the educational context is remarkably often health data directly (social care, injury, accident, self harm, mental health) or indirectly (mood and emotion or eating patterns).

Children’s data in education is increasingly bodily data. An AI education company CEO was even reported to have considered, “bone-mapping software to track pupils’ emotions” linking a child’s bodily data and data of the mind. For a report written by Pippa King and myself in 2021, The State of Biometrics 2022: A Review of Policy and Practice in UK Education, we mapped the emerging prevalence of biometrics in educational settings. Published on the ten-year anniversary of the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012, we challenged the presumption that the data protection law is complied with well, or is effective enough alone in the protection of children’s data or digital rights.

We mustn’t forget, when talking about data in education, children do not go to school in order to produce data or to have their lives recorded, monitored or profiled through analytics. It’s not the purpose of their activity. They go to school to exercise their right in law to receive education, that data production is a by-product of the activity they are doing.

Education data as a by product of the process

Thinking of these together as children’s lives in by-products used by others, reminded me of the Alder Hey scandal published over twenty years ago, but going back decades. In particular, the inquiry considered the huge store of body parts and residual human tissue of dead children accumulated between 1988 to 1995.

“It studied the obligation to establish ‘lack of objection’ in the event of a request to retain organs and tissue taken at a Coroner’s post-mortem for medical education and research.” (2001)

Thinking about the parallels of children’s personal data produced and extracted in education as a by-product, and organ and tissue waste a by-product of routine medical procedures in the living, highlights several lessons that we could be drawing today about digital processing of children’s lives in data and child/parental rights.

Digital bodies of the dead less protected than their physical parts

It also exposes gaps between the actual scenario today that the bodily tissue and the bodily data about deceased children could be being treated differently, since the data protection regime only applies to the living. We should really be forward looking and include rights here for all that go beyond the living “natural persons”, because our data does, and that may affect those who we leave behind. It is insufficient for researchers and others who wish to use data without restriction to object, because this merely pushes off the problem, increasing the risk of public rejection of ‘hidden’ plans later. (see DDM second reading briefing on recital 27, p 30/32),

What could we learn from handling body parts for the digital body?

In the children’s organ and tissue scandal, management failed to inform or provide suitable advice and support necessary to families.

Recommendations were made for change on consent to post-mortem examinations of children, and a new approach to consent and an NHS hospital post-mortem consent form for children and all residual tissue were adopted sector-wide.

The retention and the destruction of genetic material is considered in the parental consent process required for any testing that continues to use the bodily material from the child. In the Alder Hey debate this was about deceased children, but similar processes are in place now for obtaining parental consent to research re-use and retention for waste or ‘surplus’ tissue that comes from everyday operations on the living.

But new law in the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill is going to undermine current protections for genetic material in the future and has experts in that subject field extremely worried.

The DPDI Bill will consider the data of the dead for the first time

To date it only covers the data of or related to the living or “natural persons” and it is ironic that the rest of the Bill does the polar opposite, not about living and dead, but by redefining both personal data and research purposes it takes what is today personal data ‘in scope’ of data protection law and places it out of scope and beyond its governance due to exemptions, or changes in controller responsibility over time. Meaning a whole lot of data about children and the rest of us) will not be covered by DP law at all. (Yes, those are bad things in the Bill).

Separately, the new law as drafted, will also create a divergence from its generally accepted scope, and will start to bring data into scope the ‘personal data’ of the dead.

Perhaps as a result of limited parliamentary time, the DPDI Bill (see col. 939) is being used to include amendments on, “Retention of information by providers of internet services in connection with death of child,” to amend the Online Safety Act 2023 to enable OFCOM to give internet service providers a notice requiring them to retain information in connection with an investigation by a coroner (or, in Scotland, procurator fiscal) into the death of a child suspected to have taken their own life. The new clause also creates related offences.”

While primarily for the purposes of formal investigation into the role of social media in children’s suicide, and directions from Ofcom to social media companies to retain information for the period of one year beginning with the date of the notice, it highlights the difficulty of dealing with data after the death of a loved one.

This problem is perhaps no less acute where a child or adult has left no ‘digital handover’ via a legacy contact eg at Apple you can assign someone to be this person in the event of your own death from any cause. But what happens if your relation has not set this up and has been the holder of the digital key to your entire family photo history stored on a company’s cloud? Is this a question of data protection, or digital identity management, or of physical product ownership?

Harvesting children’s digital bodies is not what people want

In our DDM research and report, “the words we use in data policy: putting people back in the picture” we explored how the language used to talk about personal data, has a profound effect on how people think about it.

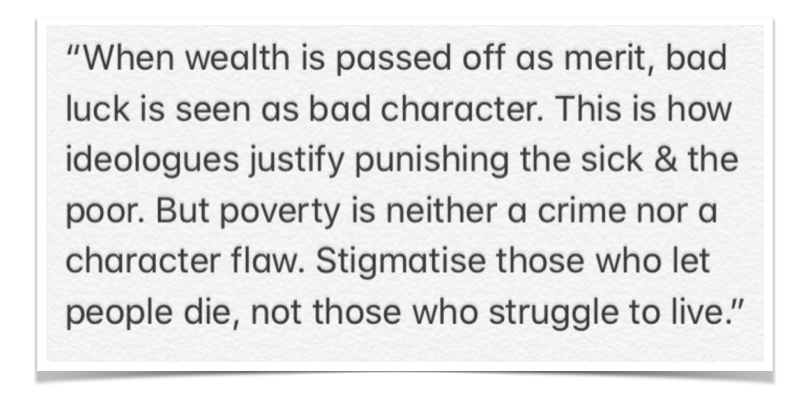

In the current digital landscape personal data can often be seen as a commodity, a product to mine, extract and exploit and pass around to others. More of an ownership and IP question and the broadly U.S. approach. Data collection is excessive in “Big Data” mountains and “data lakes”, described just like the EU food surpluses of the 1970s. Extraction and use without effective controls creates toxic waste, is polluting and met with resistance. This environment is not sustainable and not what young people want. Enforcement of the data protection principles of purpose limitation and data minimisation should be helping here, but young people don’t see it.

When personal data is considered as ‘of the body’ or bodily residue, data as part of our life, the resulting view was that data is something that needs protecting. That need is generally held to be true, and represented in European human rights-based data laws and regulation. A key aim of protecting data is to protect the person.

In a workshop for that report preparation, teenagers expressed unease that data about them being ‘harvested’ to exploit as human capital and find their rights are not adequately enabled or respected. They find data can be used to replace conversation with them, and mean they are misrepresented by it, and at the same time there is a paradox that a piece of data can be your ‘life story’ and single source of truth advocating on your behalf.

Parental and children’s rights are grafted together and need recognised processes that respect this, as managed in health

Children’s competency and parental rights are grafted together in many areas of a child’s life and death, so why not by default in the digital environment? What additional mechanisms in a process are needed where both views carry legal weight? What are the specific challenges that need extra attention in data protection law due to the characteristics of data that can be about more than one person, be controlled by and not only be about the child, and parental rights?

What might we learn for the regulation of practice of a child’s digital footprint from how health manages residual tissue processing? Who is involved, what are the steps of the process and how is it communicated onwardly accompanying data flows around a system?

Where data protection rules do not apply, certain activities may still constitute an interference with Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which protects the right to private and family life. (WP 29 Opinion 4/2007 on the concept of personal data p24).

Undoubtedly the datafied child is an inseparable ‘data double’ of the child. Data users about children, who do so without their permission, without informing them or their families, without giving children and parents the tools to exercise their rights to have a say and control their digital footprint in life and in death, might soon find themselves being treated in the same way as accountable individuals in the Alder Hey scandal were, many years after the events took place.

Minor edits and section sub-headings added on 18/12 for clarity plus a reference to the WP29 opinion 04/2007 on personal data.