Who is using all this Big Data? What decisions are being made on the back of it that we never see?

In the everyday and press it often seems that the general public does not understand data, and can easily be told things which we misinterpret.

There are tools in social media influencing public discussions and leading conversations in a different direction from that it had taken, and they operate without regulation.

It is perhaps meaningful that pro-reform Wellington School last week opted out of some of the greatest uses of Big Data sharing in the UK. League tables. Citing their failures. Deciding they were “in fact, a key driver for poor educational practice.”

Most often we cannot tell from the data provided what we are told those Big Data should be telling us. And we can’t tell if the data are accurate, genuine and reliable.

Yet big companies are making big money selling the dream that Big Data is the key to decision making. Cumulatively through lack of skills to spot inaccuracy, and inability to do necessary interpretation, we’re being misled by what we find in Big Data.

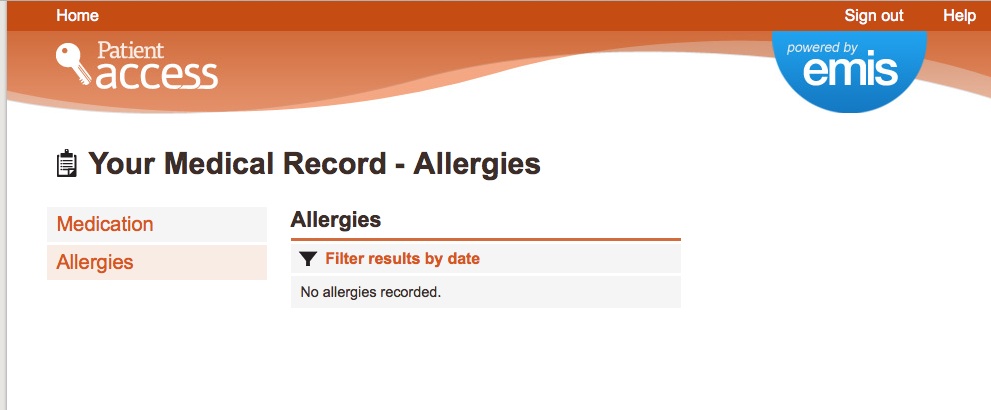

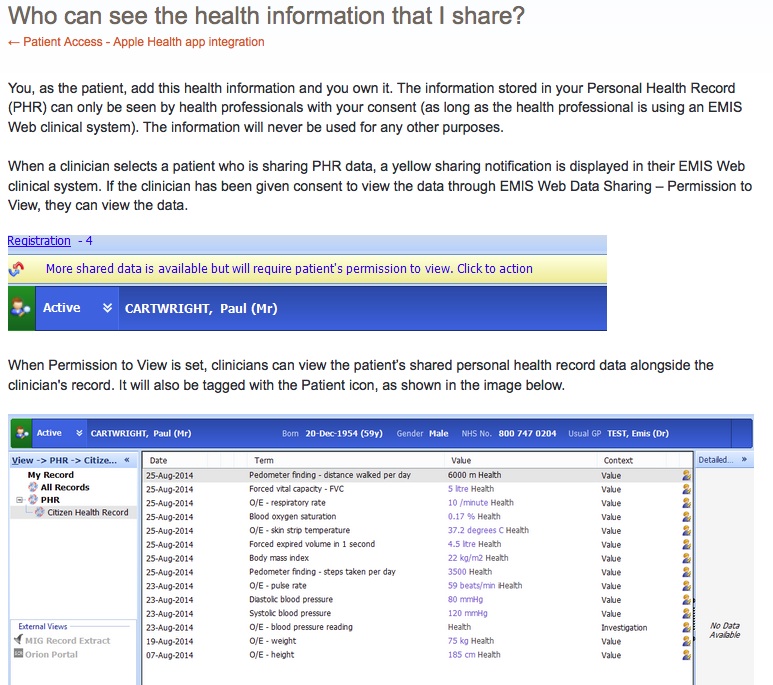

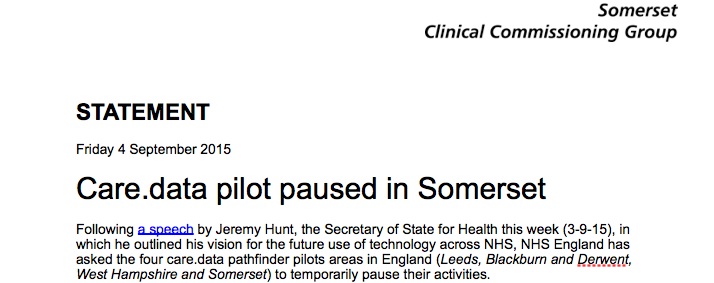

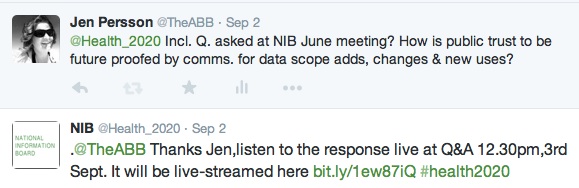

Being misled is devastating for public trust, as the botched beginnings of care.data found in 2014. Trust has come to be understood as vital for future based on datasharing. Public involvement in how we are used in Big Data in the future, needs to include how our data are used in order to trust they are used well. And interpreting those data well is vital. Those lessons of the past and present must be learned, and not forgotten.

It’s time to invest some time in thinking about safeguarding trust in the future, in the unknown, and the unseen.

We need to be told which private companies like Cinven and FFT have copies of datasets like HES, the entire 62m national hospital records, or the NPD, our entire schools database population of 20 million, or even just its current cohort of 8+ million.

If the public is to trust the government and public bodies to use our data well, we need to know exactly how those data are used today and all these future plans that others have for our personal data.

When we talk about public bodies sharing data they hold for administrative purposes, do we know which private companies this may mean in reality?

The UK government has big plans for big data sharing, sharing across all public bodies, some tailored for individual interventions.

While there are interesting opportunities for public benefit from at-scale systems, the public benefit is at risk not only from lack of trust in how systems gather data and use them, but that interoperability gets lost in market competition.

Openness and transparency can be absent in public-private partnerships until things go wrong. Given the scale of smart-cities, we must have more than hope that data management and security will not be one of those things.

But how will we know if new plans design well, or not?

Who exactly holds and manages those data and where is the oversight of how they are being used?

Using Big Data to be predictive and personal

How do we definde “best use of data” in “public services” right across the board in a world in which boundaries between private and public in the provision of services have become increasingly blurred?

UK researchers and police are already analysing big data for predictive factors at postcode level for those at risk or harm, for example in combining health and education data.

What has grown across the Atlantic is now spreading here. When I lived there I could already see some of what is deeply flawed.

When your system has been as racist in its policing and equity of punishment as institutionally systemic as it is in the US, years of cumulative data bias translates into ‘heat lists’ and means “communities of color will be systematically penalized by any risk assessment tool that uses criminal history as a legitimate criterion.”

How can we ensure British policing does not pursue flawed predictive policies and methodologies, without seeing them?

What transparency have our use of predictive prisons and justice data?

What oversight will the planned new increase in use of satellite tags, and biometrics access in prisons have?

What policies can we have in place to hold data-driven decision-making processes accountable?<

What tools do we need to seek redress for decisions made using flawed algorithms that are apparently indisputable?

Is government truly committed to being open and talking about how far the nudge unit work is incorporated into any government predictive data use? If not, why not?

There is a need for a broad debate on the direction of big data and predictive technology and whether the public understands and wants it.If we don’t understand, it’s time someone explained it.

If I can’t opt out of O2 picking up my travel data ad infinitum on the Tube, I will opt out of their business model and try to find a less invasive provider. If I can’t opt out of EE picking up my personal data as I move around Hyde park, it won’t be them.

Most people just want to be left alone and their space is personal.

A public consultation on smart-technology, and its growth into public space and effect on privacy could be insightful.

Feed me Seymour?

With the encroachment of integrated smart technology over our cities – our roads, our parking, our shopping, our parks, our classrooms, our TV and our entertainment, even our children’s toys – surveillance and sharing information from systems we cannot see start defining what others may view, or decide about us, behind the scenes in everything we do.

As it expands city wide, it will be watched closely if data are to be open for public benefit, but not invade privacy if “The data stored in this infrastructure won’t be confidential.”

If the destination of digital in all parts of our lives is smart-cities then we have to collectively decide, what do we want, what do we design, and how do we keep it democratic?

What price is our freedom to decide how far its growth should reach into public space and private lives?

The cost of smart cities to individuals and the public is not what it costs in investment made by private conglomerates.

Already the cost of smart technology is privacy inside our homes, our finances, and autonomy of decision making.

Facebook and social media may run algorithms we never see that influence our mood or decision making. Influencing that decision making is significant enough when it’s done through advertising encouraging us to decide which sausages to buy for your kids tea.

It is even more significant when you’re talking about influencing voting.

Who influences most voters wins an election. If we can’t see the technology behind the influence, have we also lost sight of how democracy is decided? The power behind the mechanics of the cogs of Whitehall may weaken inexplicably as computer driven decision from the tech companies’ hidden tools takes hold.

What opportunity and risk to “every part of government” does ever expanding digital bring?

The design and development of smart technology that makes decisions for us and about us, lies in in the hands of large private corporations, not government.

The means the public-interest values that could be built by design and their protection and oversight are currently outside our control.

There is no disincentive for companies that have taken private information that is none of their business, and quite literally, made it their business to not want to collect ever more data about us. It is outside our control.

We must plan by-design for the values we hope for, for ethics, to be embedded in systems, in policies, embedded in public planning and oversight of service provision by all providers. And that the a fair framework of values is used when giving permission to private providers who operate in public spaces.

We must plan for transparency and interoperability.

We must plan by-design for the safe use of data that does not choke creativity and innovation but both protects and champions privacy as a fundamental building block of trust for these new relationships between providers of private and public services, private and public things, in private and public space.

If “digital is changing how we deliver every part of government,” and we want to “harness the best of digital and technology, and the best use of data to improve public services right across the board” then we must see integration in the planning of policy and its application.

Across the board “the best use of data” must truly value privacy, and enable us to keep our autonomy as individuals.

Without this, the cost of smart cities growing unchecked, will be an ever growing transfer of power to the funders behind corporations and campaign politics.

The ultimate price of this loss of privacy, will be democracy itself.

****

This is the conclusion to a four part set of thoughts: On smart technology and data from the Sprint16 session (part one). I thought about this more in depth on “Smart systems and Public Services” here (part two), and the design and development of smart technology making “The Best Use of Data” here looking at today in a UK company case study (part three) and this part four, “The Best Use of Data” used in predictions and the Future.

![Building Public Trust [2]: a detailed approach to understanding Public Trust in data sharing](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Trust-e1426443553441-672x372.jpg)