Part three: It is vital that the data sharing consultation is not seen in a silo, or even a set of silos each particular to its own stakeholder. To do it justice and ensure the questions that should be asked are answered, we must look instead at the whole story and the background setting. And we must ask each stakeholder, what does your happy ending look like?

Parts one and two to follow address public engagement and ethics, this focuses on current national data practice, tailored public services, and local impact of the change and transformation that will result.

What is your happy ending?

This data sharing consultation is gradually revealing to me how disjoined government appears in practice and strategy. Our digital future, a society that is more inclusive and more just, supported by better uses of technology and data in ‘dot everyone’ will not happen if they cannot first join the dots across all of Cabinet thinking and good practice, and align policies that are out of step with each other.

Last Thursday night’s “Government as a Platform Future” panel discussion (#GaaPFuture) took me back to memories of my old job, working in business implementations of process and cutting edge systems. Our finest hour was showing leadership why success would depend on neither. Success was down to local change management and communications, because change is about people, not the tech.

People in this data sharing consultation, means the public, means the staff of local government public bodies, as well as the people working at national stakeholders of the UKSA (statistics strand), ADRN (de-identified research strand), Home Office (GRO strand), DWP (Fraud and Debt strands), and DECC (energy) and staff at the national driver, the Cabinet Office.

I’ve attended two of the 2016 datasharing meetings, and am most interested from three points of view – because I am directly involved in the de-identified data strand, campaign for privacy, and believe in public engagement.

Engagement with civil society, after almost 2 years of involvement on three projects, and an almost ten month pause in between, the projects had suddenly become six in 2016, so the most sensitive strands of the datasharing legislation have been the least openly discussed.

At the end of the first 2016 meeting, I asked one question.

How will local change management be handled and the consultation tailored to local organisations’ understanding and expectations of its outcome?

Why? Because a top down data extraction programme from all public services opens up the extraction of personal data as business intelligence to national level, of all local services interactions with citizens’ data. Or at least, those parts they have collected or may collect in future.

That means a change in how the process works today. Global business intelligence/data extractions are designed to make processes more efficient, through reductions in current delivery, yet concrete public benefits for citizens are hard to see that would be different from today, so why make this change in practice?

What it might mean for example, would be to enable collection of all citizens’ debt information into one place, and that would allow the service to centralise chasing debt and enforce its collection, outsourced to a single national commercial provider.

So what does the future look like from the top? What is the happy ending for each strand, that will be achieved should this legislation be passed? What will success for each set of plans look like?

What will we stop doing, what will we start doing differently and how will services concretely change from today, the current state, to the future?

Most importantly to understand its implications for citizens and staff, we should ask how will this transformation be managed well to see the benefits we are told it will deliver?

Can we avoid being left holding a pumpkin, after the glitter of ‘use more shiny tech’ and government love affair with the promises of Big Data wear off?

Look into the local future

Those with the vision of the future on a panel at the GDS meeting this week, the new local government model enabled by GaaP, also identified, there are implications for potential loss of local jobs, and “turkeys won’t vote for Christmas”. So who is packaging this change to make it successfully deliverable?

If we can’t be told easily in consultation, then it is not a clear enough policy to deliver. If there is a clear end-state, then we should ask what the applied implications in practice are going to be?

It is vital that the data sharing consultation is not seen in a silo, or even a set of silos each particular to its own stakeholder, about copying datasets to share them more widely, but that we look instead at the whole story and the background setting.

The Tailored Reviews: public bodies guidance suggests massive reform of local government, looking for additional savings, looking to cut back office functions and commercial plans. It asks “What workforce reductions have already been agreed for the body? Is there potential to go further? Are these linked to digital savings referenced earlier?”

Options include ‘abolish, move out of central government, commercial model, bring in-house, merge with another body.’

So where is the local government public bodies engagement with change management plans in the datasharing consultation as a change process? Does it not exist?

I asked at the end of the first datasharing meeting in January and everyone looked a bit blank. A question ‘to take away’ turned into nothing.

Yet to make this work, the buy-in of local public bodies is vital. So why skirt round this issue in local government, if there are plans to address it properly?

If there are none, then with all the data in the world, public services delivery will not be improved, because the issues are friction not of interference by consent, or privacy issues, but working practices.

If the idea is to avoid this ‘friction’ by removing it, then where is the change management plan for public services and our public staff?

Trust depends on transparency

John Pullinger, our National Statistician, this week also said on datasharing we need a social charter on data to develop trust.

Trust can only be built between public and state if the organisations, and all the people in them, are trustworthy.

To implement process change successfully, the people involved in these affected organisations, the staff, must trust that change will mean positive improvement and risks explained.

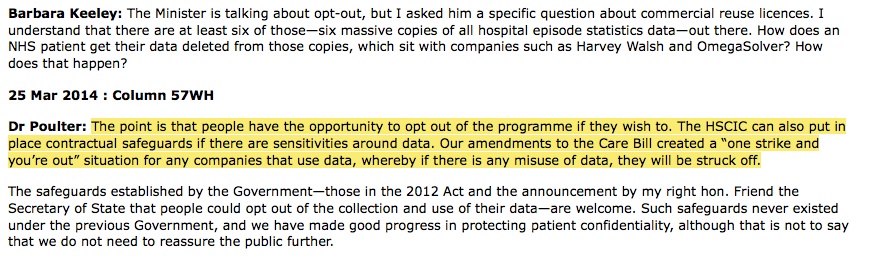

For the public, what defined levels of data access, privacy protection, and scope limitation that this new consultation will permit in practice, are clearly going to be vital to define if the public will trust its purposes.

The consultation does not do this, and there is no draft code of conduct yet, and no one is willing to define ‘research’ or ‘public interest’.

Public interest models or ‘charter’ for collection and use of research data in health, concluded that ofr ethical purposes, time also mattered. Benefits must be specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time-bound. So let’s talk about the intended end state that is to be achieved from these changes, and identify how its benefits are to meet those objectives – change without an intended end state will almost never be successful, if you don’t know start knowing what it looks like.

For public trust, that means scope boundaries. Sharing now, with today’s laws and ethics is only fully meaningful if we trust that today’s governance, ethics and safeguards will be changeable in future to the benefit of the citizen, not ever greater powers to the state at the expense of the individual. Where is scope defined?

There is very little information about where limits would be on what data could not be shared, or when it would not be possible to do so without explicit consent. Permissive powers put the onus onto the data controller to share, and given ‘a new law says you should share’ would become the mantra, it is likely to mean less individual accountability. Where are those lines to be drawn to support the staff and public, the data user and the data subject?

So to summarise, so far I have six key questions:

- What does your happy ending look like for each data strand?

- How will bad practices which conflict with the current consultation proposals be stopped?

- How will the ongoing balance of use of data for government purposes, privacy and information rights be decided and by whom?

- In what context will the ethical principles be shaped today?

- How will the transformation from the current to that future end state be supported, paid for and delivered?

- Who will oversee new policies and ensure good data science practices, protection and ethics are applied in practice?

This datasharing consultation is not entirely for something new, but expansion of what is done already. And in some places is done very badly.

How will the old stories and new be reconciled?

Wearing my privacy and public engagement hats, here’s an idea.

Perhaps before the central State starts collecting more, sharing more, and using more of our personal data for ‘tailored public services’ and more, the government should ask for a data amnesty?

It’s time to draw a line under bad practice. Clear out the ethics drawers of bad historical practice, and start again, with a fresh chapter. Because current practices are not future-proofed and covering them up in the language of ‘better data ethics’ will fail.

The consultation assures us that: “These proposals are not about selling public or personal data, collecting new data from citizens or weakening the Data Protection Act 1998.”

However it does already sell out personal data from at least BIS. How will these contradictory positions across all Departments be resolved?

The left hand gives out de-identified data in safe settings for public benefit research while the right hands out over 10 million records to the Telegraph and The Times without parental or schools’ consent. Only in la-la land are these both considered ethical.

Will somebody at the data sharing meeting please ask, “when will this stop?” It is wrong. These are our individual children’s identifiable personal data. Stop giving them away to press and charities and commercial users without informed consent. It’s ludicrous. Yet it is real.

Policy makers should provide an assurance there are plans for this to change as part of this consultation.

Without it, the consultation line about commercial use, is at best disingenuous, at worst a bare cheeked lie.

“These powers will also ensure we can improve the safe handling of citizen data by bringing consistency and improved safeguards to the way it is handled.”

Will it? Show me how and I might believe it.

Privacy, it was said at the RSS event, is the biggest concern in this consultation:

“includes proposals to expand the use of appropriate and ethical data science techniques to help tailor interventions to the public”

“also to start fixing government’s data infrastructure to better support public services.”

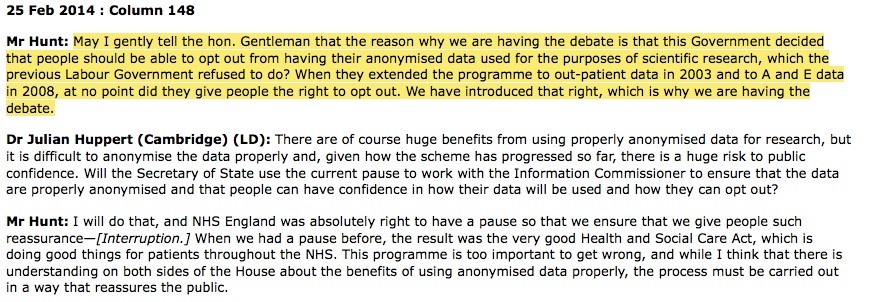

The techniques need outlined what they mean, and practices fixed now, because many stand on shaky legal ground. These privacy issues have come about over cumulative governments of different parties in the last ten years, so the problems are non-partisan, but need practical fixes.

Today, less than transparent international agreements push ‘very far-reaching chapters on the liberalisation of data trading’ while according to the European Court of Justice these practices lack a solid legal basis.

Today our government already gives our children’s personal data to commercial third parties and sells our higher education data without informed consent, while the DfE and BIS both know they fail processing and its potential consequences: the European Court reaffirmed in 2015 “persons whose personal data are subject to transfer and processing between two public administrative bodies must be informed in advance” in Judgment in Case C-201/14.

In a time that actively cultivates universal public fear, it is time for individuals to be brave and ask the awkward questions because you either solve them up front, or hit the problems later. The child who stood up and said The Emperor has on no clothes, was right.

What’s missing?

The consultation conversation will only be genuine, once the policy makers acknowledge and address solutions regards:

- those data practices that are currently unethical and must change

- how the tailored public services datasharing legislation will shape the delivery of government services’ infrastructure and staff, as well as the service to the individual in the public.

If we start by understanding what the happy ending looks like, we are much more likely to arrive there, and how to measure success.

The datasharing consultation engagement, the ethics of data science, and impact on data infrastructures as part of ‘government as a platform’ need seen as a whole joined up story if we are each to consider what success for us as stakeholders, looks like.

We need to call out current data failings and things that are missing, to get them fixed.

Without a strong, consistent ethical framework you risk 3 things:

- data misuse and loss of public trust

- data non-use because your staff don’t trust they’re doing it right

- data is becoming a toxic asset

The upcoming meetings should address this and ask practically:

- How the codes of conduct, and ethics, are to be shaped, and by whom, if outwith the consultation?

- What is planned to manage and pay for the future changes in our data infrastructures; ie the models of local government delivery?

- What is the happy ending that each data strand wants to achieve through this and how will the success criteria be measured?

Public benefit is supposed to be at the heart of this change. For UK statistics, for academic public benefit research, they are clear.

For some of the other strands, local public benefits that outweigh the privacy risks and do not jeopardise public trust seem like magical unicorns dancing in the land far, far away of centralised government; hard to imagine, and even harder to capture.

*****

Part one: A data sharing fairytale: Engagement

Part two: A data sharing fairytale: Ethics

Part three: A data sharing fairytale: Impact (this post)

Tailored public bodies review: Feb 2016

img credit: Hermann Vogel illustration ‘Cinderella’

![smartphones: the single most important health treatment & diagnostic tool at our disposal [#NHSWDP 2]](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/IMG_4563-e1427130930127-672x372.jpg)