‘People, ideas, machines — in that order.’ This quote in that latest blog by Dominic Cummings is spot on, but the blind spots or the deliberate scoping the blog reveals, are both just as interesting.

If you want to “figure out what characters around Putin might do”, move over Miranda. If your soul is for sale, then this might be the job for you. This isn’t anthropomorphism of Cummings, but an excuse to get in the parallels to Meryl Streep’s portrayal of Priestly.

“It will be exhausting but interesting and if you cut it you will be involved in things at the age of 21 that most people never see.”

Comments like these make people who are not of that mould, feel of less worth. Commitment comes in many forms. People with kids and caring responsibilities, may be some of your most loyal staff. You may not want them as your new PA, but you will almost certainly, not want to lose them across the board.

Some words would be wise in follow up to existing staff, the thousands of public servants we have today, after his latest post.

1. The blog is aimed at a certain kind of men. Speak to women too.

The framing of this call for staff is problematic, less for its suggested work ethic, than the structural inequalities it appears to purposely perpetuate. Despite the poke at public school bluffers. Do you want the best people around you, able to play well with others, or not?

I am disappointed that asking for “the sort of people we need to find” is designed, intentionally or not, to appeal to a certain kind of men. Even if he says it should be diverse and includes people, “like that girl hired by Bigend as a brand ‘diviner.'”

If Cummings is intentional about hiring the best people, then he needs to do by better by women. We already have a PM that many women would consider toxic to work around, and won’t as a result.

Some of the most brilliant, cognitively diverse, young people I know who fit these categories well, — and across the political spectrum–are themselves diverse by nature and expect their surroundings to be. They (unlike our generation), do not “babble about ‘gender identity diversity blah blah’.” Woke is not an adjective that needs explained, but a way of life. Put such people off by appearing to devalue their norms, and you’ll miss out on some potential brilliant applicants from the pool, which will already be self-selecting, excluding many who simply won’t work for you, or Boris, or Brexit blah blah. People prepared to burn out as you want them to, aren’t going to be at their best for long. And it takes a long time to recover.

‘That girl’ was the main character, and her name was Cayce Pollard. Women know why you should say her name. Fewer women will have worked at CERN, perhaps for related reasons, compared with “the ideal candidate” described in this call.

“If you want an example of the sort of people we need to find in Britain, look at this’ he writes of C.C. Myers, with a link to, ‘On the Cover: The World’s Fastest Man.“

Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett, Alexander Grothendieck, Bret Victor, von Neumann, Cialdini. Groves, Mueller, Jain, Pearl, Kay, Gibson, Grove, Makridakis, Yudkowsky, Graham and Thiel.

The *men illustrated* list, goes on and on.

What does it matter how many lovers you have if none of them gives you the universe?

Not something I care to discuss over dinner either.

But women of all ages do care that our PM appears to be a cad. It matters therefore that your people be seen to work to a better standard. You want people loyal to your cause, and the public to approve, even if they don’t of your leader. Leadership goes far beyond electoral numbers and a mandate.

Women — including those that tick the skill boxes need, yet again, to look beyond the numbers and have to put up with a lot. This advertorial appeals to Peter Parker, when the future needs more of Miles Morales. Fewer people with the privilege and opportunity to work at the Large Hadron Collider, and more of those who stop Kingpin’s misuse and shut it down.

A different kind of the same kind of thing, isn’t real change. This call for something new, is far less radical than it is being portrayed as.

2. Change. Don’t forget to manage it by design.

In fact, the speculation that this is all change, hiring new people for new stuff [some of which elsewhere he has genuinely interesting ideas on, like, “decentralisation and distributed control to minimise the inevitable failures of even the best people”] doesn’t really feature here, rather it is something of a precursor. He’s starting less with building the new, and rather with let’s ‘drain the swamp’ of bureaucracy. The Washington-style of 1980’s Reagan, including, ‘let’s put in some more of our kind of people’.

His personal brand of longer-term change may not be what some of his cheerleaders think it will be, but if the outcome is the same and seen to be ‘showing these Swamp creatures the zero mercy they deserve‘, [sic] does intent matter? It does, and he needs to describe his future plans better, if he wants to have a civil service that works well.

The biggest content gap (leaving actual policy content aside) is any appreciation of the current, and need for change management.

Training gets a mention; but new process success, depends on effectively communicating on change, and delivering training about it to all, not only those from whom you expect the most high performance. People not projects, remember?

Change management and capability transfer delivered by costly consultants, is not needed, but making it understandable not elitist, is.

- genuinely present an understanding of the as-is, (I get you and your org, for change *with* you, not to force change upon you)

- communicating what the future model is going to move towards (this is why you want to change and what good looks like), and

- a roadmap of how you expect the organisation to get there (how and when), that need not be constricted by artificial comms grids.

Because people and having their trust, are what make change work.

On top of the organisational model, *every* member of staff must know where their own path fits in, and if their role is under threat, whether training will be offered to adapt, or whether they will be made redundant. Uncertainty around this over time, is also toxic. You might not care if you lose people along the way. You might consider these the most expendable people. But if people are fearful and unhappy in your organisation, or about their own future, it will hold them back from delivering at their best, and the organisation as a result. And your best will leave, as much as those who are not.

“How to build great teams and so on”, is not a bolt-on extra here, it is fundamental. You can’t forget the kitchens. But changing the infrastructure alone, cannot deliver real change you want to see.

3. Communications. Neither propaganda and persuasion nor PR.

There is not such a vast difference between the business of communications as a campaign tool, and tool for control. Persuasion and propaganda. But where there may be a blind spot in the promotion of the Cialdini-six style comms, is that behavioural scientists that excel at these, will not use the kind of communication tools that either the civil service nor the country needs for the serious communications of change, beyond the immediate short term.

Five thoughts:

- Your comms strategy should simply be “Show the thing. Be clear. Be brief.”

- Communicating that failure is acceptable, is only so if it means learning from it.

- If policy comms plans depend on work led by people like you, who like each other and like you, you’ll be told what you want to hear.

- Ditto, think tanks that think the same are not as helpful as others.

- And you need grit in the oyster for real change.

As an aside, for anyone having kittens about using an unofficial email to get around FOI requests and think it a conspiracy to hide internal communications, it really doesn’t work that way. Don’t panic, we know where our towel is.

4. The Devil craves DARPA. Build it with safe infrastructures.

Cumming’s long-established fetishing of technology and fascination with Moscow will be familiar to those close, or blog readers. They are also currently fashionable, again. The solution is therefore no surprise, and has been prepped in various blogs for ages. The language is familiar. But single-mindedness over this length of time, can make for short sightedness.

In the US. DARPA was set up in 1958 after the Soviet Union launched the world’s first satellite, with a remit to “prevent technological surprise” and pump money into “high risk, high reward” projects. (Sunday Times, Dec 28, 2019)

In March, Cummings wrote in praise of Project Maven;

“The limiting factor for the Pentagon in deploying advanced technology to conflict in a useful time period was not new technical ideas — overcoming its own bureaucracy was harder than overcoming enemy action.”

Almost a year after that project collapsed, its most interesting feature was surely not the role of bureaucracy among tech failure. Maven was a failure not of tech, nor bureaucracy, but to align its values with the decency of its workforce. Whether the recallibration of its compass as a company is even possible, remains to be seen.

If firing staff who hold you to account against a mantra of ‘don’t be evil’ is championed, this drive for big tech values underpinning your staff thinking and action, will be less about supporting technology moonshots, than a shift to the Dark Side of capitalist surveillance.

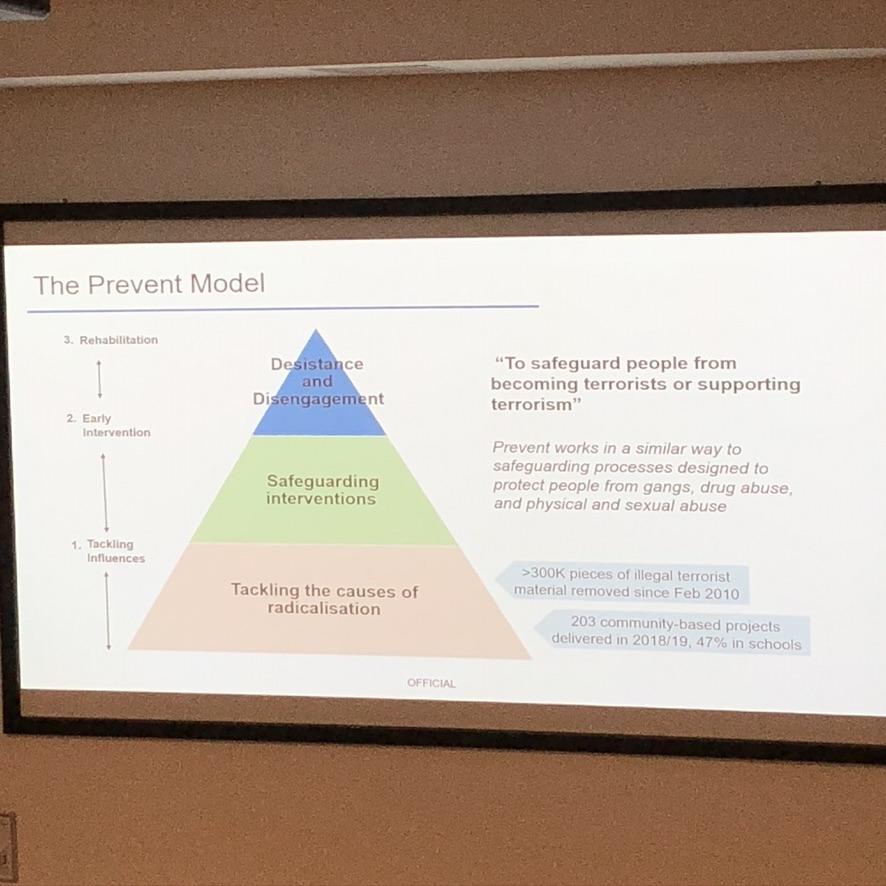

The incessant narrative focus on man and the machine –machine learning, —the machinery of government, quantitative models and the frontiers of the science of prediction is an obsession with power. The downplay of the human in that world —is displayed in so many ways, but the most obvious is the press and political narrative of a need to devalue human rights, — and yet to succeed, tech and innovation needs an equal and equivalent counterweight, in accountability under human rights and the law, so that when systems fail people, they do not cause catastrophic harm at scale.

“Practically nobody is ever held accountable regardless of the scale of failure,“ you say? How do you measure your own failure? Or the failure of policy? Transparency over that, and a return to Ministerial accountability are changes I would like to see. Or how about demanding accountability for algorithms that send children to social care, of which the CEO has said his failure is only measured by a Local Authority not saving money as a result of using their system?

We must stop state systems failing children, if they are not to create a failed society.

A UK DARPA-esque, devolved hothousing for technology will fail, if you don’t shore up public trust. Both in the state and commercial sectors. An electoral mandate won’t last, nor reach beyond its scope for long. You need a social licence to have legitimacy for tech that uses public data, that is missing today. It is bone-headed and idiotic that we can’t get this right as a country. Despite knowing how to, if government keeps avoiding doing it safely, it will come at a cost.

The Pentagon certainly cares about the implications for national security when the personal data of millions of people could be open to exploitation, blackmail or abuse.

You might of course, not care. But commercial companies will when they go under. The electorate will. Your masters might if their legacy will suffer and debate about the national good and the UK as a Life Sciences centre, all come to naught.

There was little in this blog, of the reality of what these hires should deliver beyond more tech and systems’ change. But the point is to make systems that work for people, not see more systems at work.

We could have it all, but not if you spaff our data laws up the wall.

“But the ship can’t sink.”

“She is made of iron, sir. I assure you, she can. And she will. It is a mathematical certainty.“

[Attributed to Thomas Andrews, Chief Designer of the RMS Titanic.]

5. The ‘circle of competence’ needs values, not only to value skills.

It’s important and consistent behaviour that Cummings says he recognises his own weaknesses, that some decisions are beyond his ‘circle of competence’ and that he should in in effect become redundant, having brought in, “the sort of expertise supporting the PM and ministers that is needed.” Founder’s syndrome is common to organisations and politics is not exempt. But neither is the Peter principle a phenomenon particular to only the civil service.

“One of the problems with the civil service is the way in which people are shuffled such that they either do not acquire expertise or they are moved out of areas they really know to do something else.”

But so what? what’s worse, is politics has not only the Peter’s but the Dilbert principle when it comes to senior leadership. You can’t put people in positions expected to command respect when they tell others to shut up and go away. Or fire without due process. If you want orgs to function together at scale, especially beyond the current problems with silos, they need people on the ground who can work together, and have a common goal who respect those above them, and feel it is all worthwhile. Their politics don’t matter. But integrity, respect and trust do, even if they don’t matter to you personally.

I agree wholeheartedly that circles of competence matter [as I see the need to build some in education on data and edTech]. Without the appropriate infrastructure change, radical change of policy is nearly impossible. But skill is not the only competency that counts when it comes to people.

If the change you want is misaligned with people’s values, people won’t support it, no matter who you get to see it through. Something on the integrity that underpins this endeavour, will matter to the applicants too. Most people do care how managers treat their own.

The blog was pretty clear that Cummings won’t value staff, unless their work ethic, skills and acceptance will belong to him alone to judge sufficient or not, to be “binned within weeks if you don’t fit.”

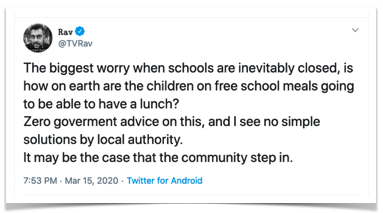

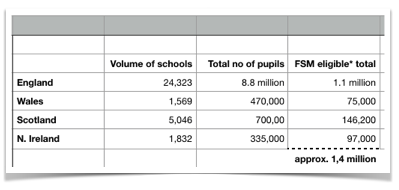

This government already knows it has treated parts of the public like that for too long. Policy has knowingly left some people behind on society’s scrap heap, often those scored by automated systems as inadequate. Families in-work moved onto Universal Credit, feed their children from food banks for #5WeeksTooLong. The rape clause. Troubled families. Children with special educational needs battling for EHC plan recognition without which schools won’t take them, and DfE knowingly underfunding suitable Alternative Provision in education by a colossal several hundred per cent amount per place, by design.

The ‘circle of competence’ needs to recognise what happens as a result of policy, not only to place value on the skills in its delivery or see outcomes on people as inevitable or based on merit. Charlie Munger may have said, “At the end of the day – if you live long enough – most people get what they deserve.”

An awful lot of people deserve a better standard of living and human dignity than the UK affords them today. And we can’t afford not to fix it. A question for new hires: How will you contribute to doing this?

6. Remember that our civil servants, are after all, public servants.

The real test of competence, and whether the civil service delivers for the people whom they serve, is inextricably bound with government policy. If its values, if its ethics are misguided, building a new path with or without new people, will be impossible.

The best civil servants I have worked with, have one thing in common. They have a genuine desire to make the world better. [We can disagree on what that looks like and for whom, on fraud detection, on immigration, on education, on exploitation of data mining and human rights, or the implications of the law. Their policy may bring harm, but their motivation is not malicious.] Your goal may be a ‘better’ civil service. They may be more focussed on better outcomes for people, not systems. Lose sight of that, and you put the service underpinning government, at risk. Not to bring change for good, but to destroy the very point of it. Keep the point of a better service, focussed on the improvement for the public.

Civil servants civilly serve in the words of Stefan Czerniawski. These plans will need challenge to be the best they can be. As pubstrat asked, so should we all ask Cummings to outline his thoughts on:

- “What makes the decisions which civil servants implement legitimate?

- Where are the boundaries of that legitimacy and how can they be detected?

- What should civil servants do if those boundaries are reached and crossed?”

Self-destruction for its own sake, is not a compelling narrative for change, whether you say you want to control that narrative, or not.

Two hands are a lot, but many more already work in the civil service. If Cummings only works against them, he’ll succeed not in building change, but resistance.