At Conservative Party Conference (“CPC22”) yesterday, the CSJ Think Tank hosted an event called, The Children of Lockdown: Where are they now?

When the speakers were finished, and other questions had been asked, I had the opportunity to raise the following three points.

They matter to me because I am concerned that bad policy-making for children will come from the misleading narrative based on bad data. The data used in the discussion is bad data for a number of reasons, based on our research over the last 4 years at defenddigitalme, and previously as part of the Counting Children coalition with particular regard to the Schools Bill.

The first is a false fact that has been often bandied about over the last year in the media and in Parliamentary debate, and that the Rt Hon Sir Iain Duncan Smith MP repeated in opening the panel discussion, that 100,000 children have not returned to school, “as a result of all of this“.

Full Fact has sought to correct this misrepresentation by individuals and institutions in the public domain several times, including one year ago today, when a Sunday Times article, published on 3 October 2021, claimed new figures showed “that between 95,000 and 135,000 children did not return to school in the autumn term, credited to the Commission on Young Lives, a task force headed up by former Children’s Commissioner for England.” Anne Longfield had then told Full Fact, that on 16 September 2021, “the rate of absence was around 1.5 percentage points higher than would normally be expected in the autumn term pre-pandemic.”

Full Fact wrote, “This analysis attempts to highlight an estimated level of ‘unexplained absence’, and comes with a number of caveats—for example it is just one day’s data, and it does not record or estimate persistent absence.”

There was no attempt made in the CPC22 discussion to disaggregate the “expected” absence rate from anything on top, and presenting the idea as fact, that 100,000 children have not returned to school, “as a result of all of this”, is misleading.

Suggesting this causation for 100,000 children is wrong for two reasons. The first, is not talking about the number of children within that number who were out of school before the pandemic and reasons for that. The CSJ’s own report published in 2021, said that, “In the autumn term of 2019, i.e pre-Covid 60,244 pupils were labeled as severely absent.”

Whether it is the same children or not who were out of school before and afterwards also matters to apply causation. This named pupil-level absence data is already available for every school child at national level on a termly basis, alongside the other personal details collected termly in the school census, among other collections.

Full Fact went on to say, “The Telegraph reported in April 2021 that more than 20,000 children had “fallen off” school registers when the Autumn 2020 term began. The Association of Directors of Children’s Services projected that, as of October 2020, more than 75,000 children were being educated at home. However, as explained above, this is not the same as being persistently absent.”

The second point I made yesterday, was that the definition of persistent absence has changed three times since 2010, so that children are classified as persistently absent more quickly now at 10%, than when it meant 20% or more of sessions were missed.

(It’s also worth noting that data are inconsistent over time in another way too. The 2019 Guide to Absence Statistics draws attention to the fact that, “Year on year comparisons of local authority data may be affected by schools converting to academies.”)

And third and finally, I pointed out where we have found a further problem in counting children correctly. Local Authorities do this in different ways. Some count each actual child once in the year in their data, some count each time a child changes status (i.e a move from mainstream into Alternative Provision to Elective Home Education could see the same child counted three times in total, once in each dataset across the same year), and some count full-time equivalent funded places (i.e. if five children each have one day a week outside mainstream education, they would be counted only as one single full-time child in total in the reported data).

Put together, this all means not only that the counts are wrong, but the very idea of “ghost children” who simply ‘disappear’ from school without anything known about them anywhere at all, is a fictitious and misleading presentation.

All schools (including academies and independent schools) must notify their local authority when they are about to remove a pupil’s name from the school admission register under any of the fifteen grounds listed in Regulation 8(1) a-n of the Education (Pupil Registration) (England) Regulations 2006. On top of that, children are recorded as Children Missing Education, “CME” where the Local Authority decides a child is not in receipt of suitable education.

For those children, processing of personal data of children not-in-school by Local Authorities is already required under s436Aof the The Education Act 1996, Duty to make arrangements to identify children not receiving education.

Research done as part of the Counting Children coalition with regards to the Schools Bill, has found every Local Authority that has replied to date (with a 67% response rate to FOI on July 5, 2022) upholds its statutory duty to record these children who either leave state education, or who are found to be otherwise missing education. Every Local Authority has a record of these children, by name, together with much more detailed data.** The GB News journalist on the panel said she had taken her children out of school and the Local Authority had not contacted her. But as a home-educating audience member then pointed out, that does not mean therefore the LA did not know about her decision, since they would already have her child-/ren’s details recorded. There is law in place already on what LAs must track. Whether or not and how the LA is doing its job, was beyond this discussion, but the suggestion that more law is needed to make them collect the same data as is already required is superfluous.

This is not only about the detail of context and nuance in the numbers and its debate, but substantially alters the understanding of the facts. This matters to have correct, so that bad policy doesn’t get made based on bad data and misunderstanding the conflated causes.

Despite this, in closing Iain Duncan Smith asked the attendees to go out from the meeting and evangelise about these issues. If they do so based on his selection of ‘facts’ they will spread misinformation.

At the event, I did not mention two further parts of this context that matter if policy makers and the public are to find solutions to what is no doubt an important series of problems, and that must not be manipulated to present as if they are entirely as a result of the pandemic. And not only the pandemic, but lockdowns specifically.

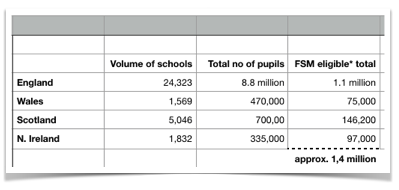

A pupil on-roll is identified as a persistent absentee if they miss 10% or more of their possible sessions (one school day has two sessions, morning and afternoon.) 1.1% of pupil enrolments missed 50% or more of their possible sessions in 2020/21. Children with additional educational and health needs or disability, have higher rates of absence. During Covid, the absence rate for pupils with an EHC plan was 13.1% across 2020/21.

“Authorised other reasons has risen to 0.9% from 0.3%, reflecting that vulnerable children were prioritised to continue attending school but where parents did not want their child to attend, schools were expected to authorise the absence.” (DfE data, academic year 2020/21)

While there were several references made by the panel to the impact of the pandemic on children’s poor mental health, no one mentioned the cuts to youth services’ funding by 70% over ten years, that has allowed CAMHS funding and service provision to wither and fail children well before 2020. The pandemic has exacerbated children’s pre-existing needs that the government has not only failed to meet since, but actively reduced provision for.

It was further frustrating to hear, as someone with Swedish relatives, of their pandemic approach presented as comparable with the UK and that in effect, they managed it ‘better’. It seems absurd to me, to compare the UK uncritically with a country with the population density of Sweden. But if we *are* going to do comparisons with other countries, it should be with fuller understanding of context, and all of their data, and caveats if comparison is to be meaningful.

I was somewhat surprised that Iain Duncan Smith also failed to acknowledge, even once, that thousands of people in the UK have died and continue to die or have lasting effects as a result of and with COVID-19. According to the King’s Fund report, “Overall, the number of people who have died from Covid-19 to end-July 2022 is 180,000, about 1 in 8 of all deaths in England and Wales during the pandemic.” Furthermore in England and Wales, “The pandemic has resulted in about 139,000 excess deaths“. “Among comparator high-income countries (other than the US), only Spain and Italy had higher rates of excess mortality in the pandemic to mid-2021 than the UK.” I believe that if we’re going to compare ‘lockdown success’ at all, we should look at the wider comparable data before making it. He might also have chosen to mention alongside this, the UK success story of research and discovery, and the NHS vaccination programme.

And there was no mention at all made of the further context, that while much was made of the economic harm of the impact of the pandemic on children, “The Children of Lockdown” are also, “The Children of Brexit”. It is non-partisan to point out this fact, and, I would suggest, disingenuous to leave out entirely in any discussion of the reasons for or impact of economic downturn in the UK in the last three years. In fact, the FT recently called it a “deafening silence.”

At defenddigitalme, we raised the problem of this inaccurate “counting” narrative numerous times including with MPs, members of the House of Lords in the Schools Bill debate as part of the Counting Children coalition, and in a letter to The Telegraph in March this year. More detail is here, in a blog from April.

Update May 23, 2023

Today I received the DfE held figures of he number of children who leave an educational setting for an unknown onward destination, a section of the Common Transfer Files holding space, in effect a digital limbo after leaving an educational setting until the child is ‘claimed’ by the destination. It’s known as, the Lost Pupils Database.

Furthermore, the DfE has published exploratory statistics on EHE

and ad hoc stats on CME too.

October 2022. More background:

The panel was chaired by the Rt Hon Sir Iain Duncan Smith MP and other speakers included Fraser Nelson, Editor of The Spectator Magazine; Kieron Boyle, Chief Executive Officer of Guy’s & St Thomas Foundation; the Rt Hon Robert Halfon MP, Education Select Committee Chair; and Mercy Muroki, Journalist at GB News.

We have previously offered to share our original research data and discuss with the Department for Education, and repeated this offer to the panel to help correct the false facts. I look forward in the hope they will take it up.

** Data collected in the record by Local Authorities when children are deregistered from state education (including to move to private school) may include a wide range of personal details, including as an example in Harrow: Family Name, Forename, Middle name, DOB, Unique Pupil Number (“UPN”), Former UPN, Unique Learner Number, Home Address (multi-field), Chosen surname, Chosen given name, NCY (year group), Gender, Ethnicity, Ethnicity source, Home Language, First Language, EAL (English as an additional language), Religion, Medical flag, Connexions Assent, School name, School start date, School end date, Enrol Status, Ground for Removal, Reason for leaving, Destination school, Exclusion reason, Exclusion start date, Exclusion end date, SEN Stage, SEN Needs, SEN History, Mode of travel, FSM History, Attendance, Student Service Family, Carer details, Carer address details, Carer contract details, Hearing Impairment And Visual Impairment, Education Psychology support, and Looked After status.