The Youth Endowment Fund (YEF) was established in March 2019 by children’s charity Impetus, with a £200m endowment and a ten-year mandate from the Home Office.

The YEF has just published a report as part of a series about the prevalence of relationship violence among teenagers and what schools are doing to promote healthy relationships. A total of 10,387 children aged 13-17 participated in the survey. While it rightly points out its limitations of size and sampling, its key findings include:

“Of the 10,000 young people surveyed in our report 27% have been in a romantic relationship. 49% of those said they have experienced violent or controlling behaviours from their partner.”

“Controlling behaviours are the most common, reported by 46% of those in relationships, and include behaviours such as having their partner check who they’ve been talking to on their phone or social media accounts (30%). They also include being afraid to disagree with their partner (27%) or being afraid to break up with them (26%)”, and “feeling watched or monitored (23%).”

(Source ref. pages 7 and 21).

The report effectively outlines the extent of these problems and focuses on the ‘what’ rather than the ‘why.’ But further discussing the underlying causes is also critical before making recommendations of what needs to be done. In the media, this went on to suggest schools better teach children about relationships. But if you have the wrong reasons for why any complex social problem has come about, you may reach for wrong solutions, addressing symptoms not causes.

Control Normalised in Surveillance

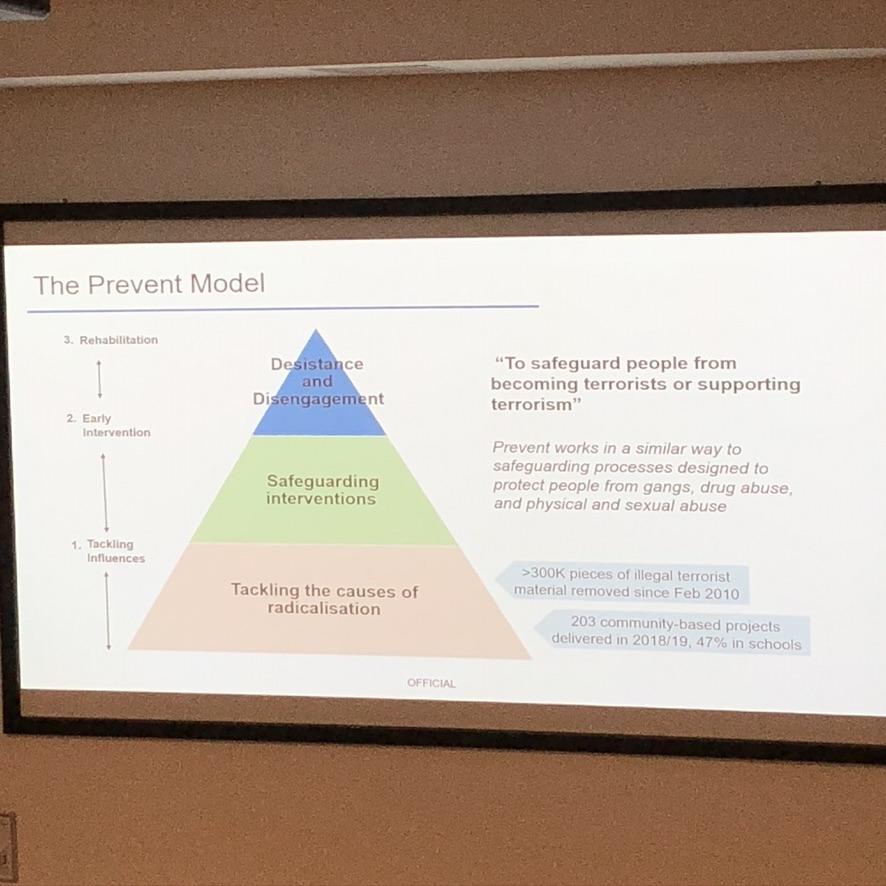

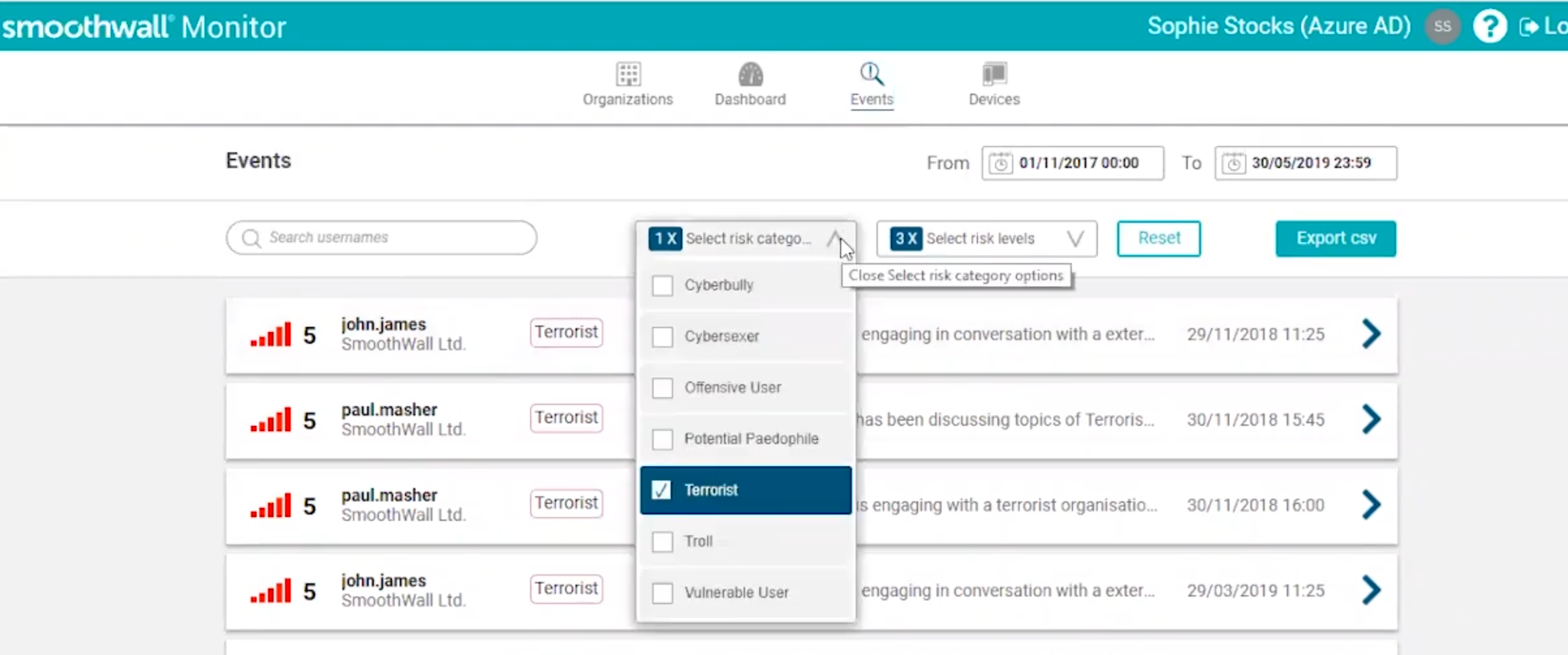

Most debate about teenagers online is about harm from content, contact, or conduct. And often the answer that comes, is more monitoring of what children do online, who they speak to on their phone or social media accounts, and controlling their activity. But research suggests that these very solutions should be analysed as part of the problem.

An omission in the report—and in broader discussions about control and violence in relationships—is the normalisation of the routine use of behavioural controls by ‘loved ones’, imposed through apps and platforms, perpetuated by parents, teachers, and children’s peers.

The growing normalisation of controlling behaviours in relationships identified in the new report—framed as care or love, such as knowing where someone is, what they’re doing, and with whom—mirrors practices in parental and school surveillance tech, widely sold as safeguarding tools for a decade. These products often operate without consent, justified as being, “in the child’s best interests,” “because we care,” or “because I love you.”

Teacher training on consent and coercive control is unlikely to succeed if staff model contradictory behaviours. “Do as I say, not as I do” tackles the wrong end of the problem.

The ‘privacy’ vs ‘protection’ debate is often polarised. This YEF report should underscore their interdependence: without privacy, children are made more vulnerable, not safer.

The Psychological Costs of Surveillance

Dr. Tonya Rooney, an academic based in Australia, has extensively studied how technology shapes childhood. She argues that,

“the effects of near-constant surveillance in schools, public spaces, and now increasingly the home environment may have far-reaching consequences for children growing up under this watchful gaze.”(Minut, 2019).

“Children become reactive agents, contributing to a cycle of suspicion and anxiety, robbing childhood of valuable opportunities to trust and be trusted.”

In the UK, while the mental health and behavioural impacts of surveillance on children—whether as the observer or the observed—remain under-researched, there is clear international and UK based evidence that parental control apps, school “safeguarding” systems, and encryption workarounds that breach confidentiality, are harming children’s interests.

- Constant monitoring creates a pervasive sense of constant scrutiny and undermines trust in a relationship. These apps and platforms are not only undermining trusted relationships today in authority whether it be families or teachers, but are detrimental to children developing trust in themselves, and others.

- Child surveillance can have negative effects on mental health through the creation of a cycle of fear and anxiety and helplessness dependent on someone else being in control, to solve it for them.

- Child surveillance has a chilling effect, not only through behavioural control of where you go, with whom, doing what, but of thought and freedom of speech, and fear of making mistakes with no space for errors to go unnoticed or unrecorded. People who are aware they are being monitored limit their self-expression and worry about what others think, which can be especially problematic for children in an educational setting, or in pursuit of curiosity and self discovery.

Research by the U.S.-based Center for Tech and Democracy (2022) highlights the disproportionate harm and discriminatory effects of pupils’ activity monitoring. Black, Hispanic, and LGBTQ+ children report experiencing higher levels of harm.

“LGBTQ+ students are even experiencing “non-consensual disclosure of sexual orientation and/or gender identity (i.e., “outing”), due to student activity monitoring.”

Children need safe spaces that are truly safe, which means trusted. The June 2024 Tipping the Balance report from the Australian eSafety Commissioner shows that LGBTIQ+ teens, for instance, rely on encrypted spaces to discuss deeply personal matters—45% of them shared private things they wouldn’t talk about face-to-face. And just over four in 10 LGBTIQ+ teens (42%) searched for mental health information at least once a week (compared with the national average of 20%).

Surveillance of Children Secures Future Markets

School “SafetyTech” practices normalise surveillance as if it were an inevitable part of life, undermining privacy as a fundamental right as a principle to be expected and respected. Some companies, even use this as a marketing feature, not a bug.

One company selling safeguarding tech to schools has framed their products as preparation for workplace device monitoring, teaching students “skills and expectations” for inevitable employment surveillance. In a 2020 EdTech UK presentation, entitled, ‘Protecting student wellness with real time monitoring‘, Netsweeper representatives described their tools as what employers want, fostering productivity by ensuring students are, “engaged, dialled in, and productive workers now and in the future.”

Many of the leading companies sell in both child and adult sectors. That the DUA Bill will give these kinds of companies’ activity in effect a ‘get-out-of-jail-free card’ for processing ‘vulnerable’ people’s data under the blanket purposes of ‘safeguarding’ — able to claim lawful grounds of legitimate interests, without needing to do any risk assessment or balancing test of harms to people’s rights—, therefore worries me a lot.

Parental Control and Perception of Harms

Parents and children perceive these tools differently when it comes to the personal, on-mobile-device, commercial markets.

Work done in the U.S. by academics at the Stevens Institute of Technology found that while parents often praise them for enhancing safety—e.g., “I can monitor everything my son does” parental negative findings were largely technical failures, such as unstable systems that crashed. Their research also found that teens found failures as harms, primarily to trust and the power dynamics in relationships. Students in the said that parental control apps as a form of “parental stalking,” and that they, “may negatively impact parent-teen relationships.”

Research done in the UK, also found children’s more nuanced understanding of privacy as a collective harm, because, “parents’ access to their messages would compromise their friends’ privacy as well: they can eves drop on your convos and stuff that you dont want them to hear […] not only is it a violation of my privacy that i didnt permit, but it is of friends too that parents dont know about”” (quoted as in original).

These researchers concluded that, “increasing evidence suggests that such apps may be bringing with them new kinds of harms associated with excessive restrictions and privacy invasion.“

A Call for Change

Academic evidence increasingly shows the harm caused by these apps in intra-familial relationships, and between schools and pupils, but research seems to be missing on the impact on children’s emotional and cognitive development and in turn, any effects in their own romantic relationships.

I believe surveillance tools undermine their understanding of healthy relationships with each other. If some adults model controlling behaviours as ‘love and caring’ in their relationships, even inadvertently, it would come as no surprise that some young people replicate similar controlling attitudes in their own behaviour.

This is our responsibility to fix. Surveillance is not safety. If we take the emerging evidence seriously, a precautionary approach might suggest:

- Parents and teachers must change their own behaviours to prioritise trust, respect, and autonomy, giving children agency and the ability to act, without tech-solutionist monitoring.

- Regulatory action is urgently needed to address the use of surveillance technologies in schools and commercial markets.

- Policy makers should be rigorous in accepting who is making these markets, who is accountable for their actions, and for their health and safety, and efficacy and error rates standards, since they are already rolled out at scale across the public sector.

The “best interests of the child” cherry picked from part of Article 3 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child seems to have become a lazy shorthand for all children’s rights in discussion of the digital environment, and with participation, privacy and provision rights, trumped by protection. Freedoms seem forgotten. Its preamble is worth a careful read in full if you have not done so for some time. And as set out in the General comment No. 25 (2021):

“Any digital surveillance of children, together with any associated automated processing of personal data, should respect the child’s right to privacy and should not be conducted routinely, indiscriminately or without the child’s knowledge.”

If the DfE is “reviewing the content of RSHE and putting children’s wellbeing at the heart of guidance for schools” they must also review the lack of safety and quality standards, error rates, and monitoring outcomes of the effects of KCSiE digital surveillance obligations for schools.

Children need both privacy and protection —not only for their safety, but to freely develop and flourish into adulthood.

References

Alelyani, T. et al. (2019) ‘Examining Parent Versus Child Reviews of Parental Control Apps on Google Play’, in, pp. 3–21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21905-5_1. (Accessed: 4 December 2024).

CDT Report – Hidden Harms: The Misleading Promise of Monitoring Students Online’ (2022) Center for Democracy and Technology, 3 August. Available at: https://cdt.org/insights/report-hidden-harms-the-misleading-promise-of-monitoring-students-online/ (Accessed: 4 December 2024).

The Chilling Effect of Student Monitoring: Disproportionate Impacts and Mental Health Risks’ (2022) Center for Democracy and Technology, 5 May. Available at: https://cdt.org/insights/the-chilling-effect-of-student-monitoring-disproportionate-impacts-and-mental-health-risks/ (Accessed: 4 December 2024).

Growing Up in the Age of Surveillance | Minut (2019). Available at: https://www.minut.com/blog/growing-up-in-the-age-of-surveillance (Accessed: 4 December 2024).

Malik, A.S., Acharya, S. and Humane, S. (2024.) ‘Exploring the Impact of Security Technologies on Mental Health: A Comprehensive Review’, Cureus, 16(2), p. e53664. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.53664. (Accessed: 4 December 2024).

Privacy and Protection: A children’s rights approach to encryption (2023) CRIN and Defend Digital Me. Available at: https://home.crin.org/readlistenwatch/stories/privacy-and-protection (Accessed: 4 December 2024).

Teen privacy: Boyd, Danah and Marwick, Alice E., Social Privacy in Networked Publics: Teens’ Attitudes, Practices, and Strategies (September 22, 2011). A Decade in Internet Time: Symposium on the Dynamics of the Internet and Society, September 2011, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1925128

Wang, G., Zhao, J., Van Kleek, M., & Shadbolt, N. (2021). Protection or punishment? Relating the design space of parental control apps and perceptions about them to support parenting for online safety. Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work Conference, 5(CSCW2). https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:da71019d-157c-47de-a310-7e0340599e22