I’ve been struck by stories I’ve heard on the datasharing consultation, on data science, and on data infrastructures as part of ‘government as a platform’ (#GaaPFuture) in recent weeks. The audio recorded by the Royal Statistical Society on March 17th is excellent, and there were some good questions asked.

There were even questions from insurance backed panels to open up more data for commercial users, and calls for journalists to be seen as accredited researchers, as well as to include health data sharing. Three things that some stakeholders, all users of data, feel are missing from consultation, and possibly some of those with the most widespread public concern and lowest levels of public trust. [1]

What I feel is missing in consultation discussions are:

- a representative range of independent public voice

- a compelling story of needs – why tailored public services benefits citizens from whom data is taken, not only benefits data users

- the impacts we expect to see in local government

- any cost/risk/benefit assessment of those impacts, or for citizens

- how the changes will be independently evaluated – as some are to be reviewed

The Royal Statistical Society and ODI have good summaries here of their thoughts, more geared towards the statistical and research aspects of data, infrastructure and the consultation.

I focus on the other strands that use identifiable data for targeted interventions. Tailored public services, Debt, Fraud, Energy Companies’ use. I think we talk too little of people, and real needs.

Why the State wants more datasharing is not yet a compelling story and public need and benefit seem weak.

So far the creation of new data intermediaries, giving copies of our personal data to other public bodies – and let’s be clear that this often means through commercial representatives like G4S, Atos, Management consultancies and more – is yet to convince me of true public needs for the people, versus wants from parts of the State.

What the consultation hopes to achieve, is new powers of law, to give increased data sharing increased legal authority. However this alone will not bring about the social legitimacy of datasharing that the consultation appears to seek through ‘open policy making’.

Legitimacy is badly needed if there is to be public and professional support for change and increased use of our personal data as held by the State, which is missing today, as care.data starkly exposed. [2]

The gap between Social Legitimacy and the Law

Almost 8 months ago now, before I knew about the datasharing consultation work-in-progress, I suggested to BIS that there was an opportunity for the UK to drive excellence in public involvement in the use of public data by getting real engagement, through pro-active consent.

The carrot for this, is achieving the goal that government wants – greater legal clarity, the use of a significant number of consented people’s personal data for complex range of secondary uses as a secondary benefit.

It was ignored.

If some feel entitled to the right to infringe on citizens’ privacy through a new legal gateway because they believe the public benefit outweighs private rights, then they must also take on the increased balance of risk of doing so, and a responsibility to do so safely. It is in principle a slippery slope. Any new safeguards and ethics for how this will be done are however unclear in those data strands which are for targeted individual interventions. Especially if predictive.

Upcoming discussions on codes of practice [which have still to be shared] should demonstrate how this is to happen in practice, but codes are not sufficient. Laws which enable will be pushed to their borderline of legal and beyond that of ethical.

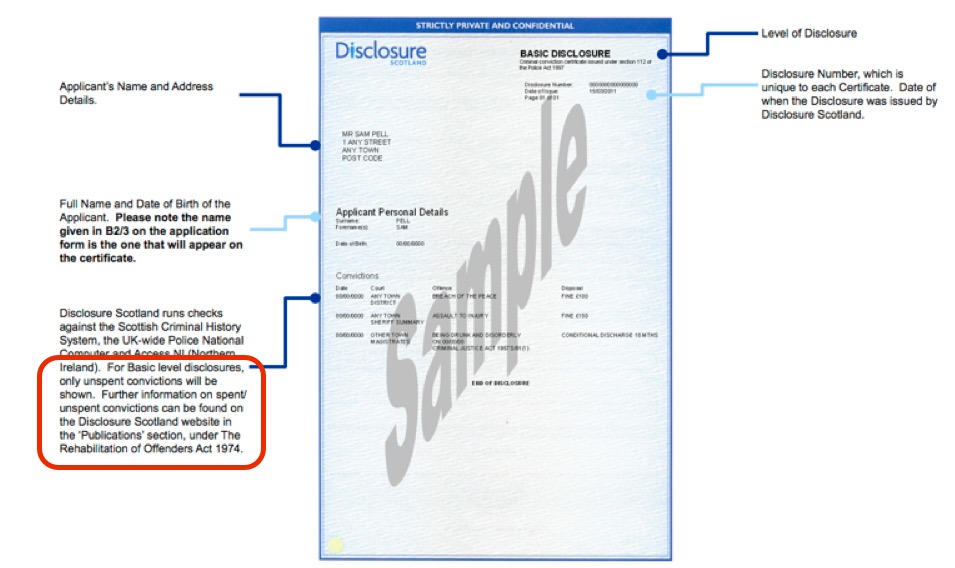

In England who would have thought that the 2013 changes that permitted individual children’s data to be given to third parties [3] for educational purposes, would mean giving highly sensitive, identifiable data to journalists without pupils or parental consent? The wording allows it. It is legal. However it fails the DPA Act legal requirement of fair processing. Above all, it lacks social legitimacy and common sense.

In Scotland, there is current anger over the intrusive ‘named person’ laws which lack both professional and public support and intrude on privacy. Concerns raised should be lessons to learn from in England.

Common sense says laws must take into account social legitimacy.

We have been told at the open policy meetings that this change will not remove the need for informed consent. To be informed, means creating the opportunity for proper communications, and also knowing how you can use the service without coercion, i.e. not having to consent to secondary data uses in order to get the service, and knowing to withdraw consent at any later date. How will that be offered with ways of achieving the removal of data after sharing?

The stick for change, is the legal duty that the recent 2015 CJEU ruling reiterating the legal duty to fair processing [4] waved about. Not just a nice to have, but State bodies’ responsibility to inform citizens when their personal data are used for purposes other than those for which those data had initially been consented and given. New legislation will not remove this legal duty.

How will it be achieved without public engagement?

Engagement is not PR

Failure to act on what you hear from listening to the public is costly.

Engagement is not done *to* people, don’t think ‘explain why we need the data and its public benefit’ will work. Policy makers must engage with fears and not seek to dismiss or diminish them, but acknowledge and mitigate them by designing technically acceptable solutions. Solutions that enable data sharing in a strong framework of privacy and ethics, not that sees these concepts as barriers. Solutions that have social legitimacy because people support them.

Mr Hunt’s promised February 2014 opt out of anonymised data being used in health research, has yet to be put in place and has had immeasurable costs for delayed public research, and public trust.

How long before people consider suing the DH as data controller for misuse? From where does the arrogance stem that decides to ignore legal rights, moral rights and public opinion of more people than those who voted for the Minister responsible for its delay?

Two years ago #nhs patients in England were made a promise that is still to be kept #caredata #datasharing @hscic pic.twitter.com/9Y83mce1DH

— Jen Persson ⭐️ (@TheABB) February 25, 2016

This attitude is what fails care.data and the harm is ongoing to public trust and to confidence for researchers’ continued access to data.

The same failure was pointed out by the public members of the tiny Genomics England public engagement meeting two years ago in March 2014, called to respond to concerns over the lack of engagement and potential harm for existing research. The comms lead made a suggestion that the new model of the commercialisation of the human genome in England, to be embedded in the NHS by 2017 as standard clinical practice, was like steam trains in Victorian England opening up the country to new commercial markets. The analogy was felt by the lay attendees to be, and I quote, ‘ridiculous.’

Exploiting confidential personal data for public good must have support and good two-way engagement if it is to get that support, and what is said and agreed must be acted on to be trustworthy.

Policy makers must take into account broad public opinion, and that is unlikely to be submitted to a Parliamentary consultation. (Personally, I first knew such processes existed only when care.data was brought before the Select Committee in 2014.) We already know what many in the public think about sharing their confidential data from the work with care.data and objections to third party access, to lack of consent. Just because some policy makers don’t like what was said, doesn’t make that public opinion any less valid.

We must bring to the table the public voice from past but recent public engagement work on administrative datasharing [5], the voice of the non-research community, and from those who are not stakeholders who will use the data but the ‘data subjects’, the public whose data are to be used.

Policy Making must be built on Public Trust

Open policy making is not open just because it says it is. Who has been invited, participated, and how their views actually make a difference on content and implementation is what matters.

Adding controversial ideas at the last minute is terrible engagement, its makes the process less trustworthy and diminishes its legitimacy.

This last minute change suggests some datasharing will be dictated despite critical views in the policy making and without any public engagement. If so, we should ask policy makers on what mandate?

Democracy depends on social legitimacy. Once you lose public trust, it is not easy to restore.

Can new datasharing laws win social legitimacy, public trust and support without public engagement?

In my next post I’ll post look at some of the public engagement work done on datasharing to date, and think about ethics in how data are applied.

*************

References:

[1] The Royal Statistical Society data trust deficit

[2] “The social licence for research: why care.data ran into trouble,” by Carter et al.

[3] FAQs: Campaign for safe and ethical National Pupil Data

[4] CJEU Bara 2015 Ruling – fair processing between public bodies

[5] Public Dialogues using Administrative data (ESRC / ADRN)

img credit: flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/