The Internet of Things (IoT) brings with it unique privacy and security concerns associated with smart technology and its use of data.

- What would it mean for you to trust an Internet connected product or service and why would you not?

- What has damaged consumer trust in products and services and why do sellers care?

- What do we want to see different from today, and what is necessary to bring about that change?

These three pairs of questions implicitly underpinned the intense day of #iotmark discussion at the London Zoo last Friday.

The questions went unasked, and could have been voiced before we started, although were probably assumed to be self-evident:

- Why do you want one at all [define the problem]?

- What needs to change and why [define the future model]?

- How do you deliver that and for whom [set out the solution]?

If a group does not agree on the need and drivers for change, there will be no consensus on what that should look like, what the gap is to achieve it, and even less on making it happen.

So who do you want the trustmark to be for, why will anyone want it, and what will need to change to deliver the aims? No one wants a trustmark per se. Perhaps you want what values or promises it embodies to demonstrate what you stand for, promote good practice, and generate consumer trust. To generate trust, you must be seen to be trustworthy. Will the principles deliver on those goals?

The Open IoT Certification Mark Principles, as a rough draft was the outcome of the day, and are available online.

Here’s my reflections, including what was missing on privacy, and the potential for it to be considered in future.

I’ve structured this first, assuming readers attended the event, at ca 1,000 words. Lists and bullet points. The background comes after that, for anyone interested to read a longer piece.

Many thanks upfront, to fellow participants, to the organisers Alexandra D-S and Usman Haque and the colleague who hosted at the London Zoo. And Usman’s Mum. I hope there will be more constructive work to follow, and that there is space for civil society to play a supporting role and critical friend.

The mark didn’t aim to fix the IoT in a day, but deliver something better for product and service users, by those IoT companies and providers who want to sign up. Here is what I took away.

I learned three things

- A sense of privacy is not homogenous, even within people who like and care about privacy in theoretical and applied ways. (I very much look forward to reading suggestions promised by fellow participants, even if enforced personal openness and ‘watching the watchers’ may mean ‘privacy is theft‘.)

- Awareness of current data protection regulations needs improved in the field. For example, Subject Access Requests already apply to all data controllers, public and private. Few have read the GDPR, or the e-Privacy directive, despite importance for security measures in personal devices, relevant for IoT.

- I truly love working on this stuff, with people who care.

And it reaffirmed things I already knew

- Change is hard, no matter in what field.

- People working together towards a common goal is brilliant.

- Group collaboration can create some brilliantly sharp ideas. Group compromise can blunt them.

- Some men are particularly bad at talking over each other, never mind over the women in the conversation. Women notice more. (Note to self: When discussion is passionate, it’s hard to hold back in my own enthusiasm and not do the same myself. To fix.)

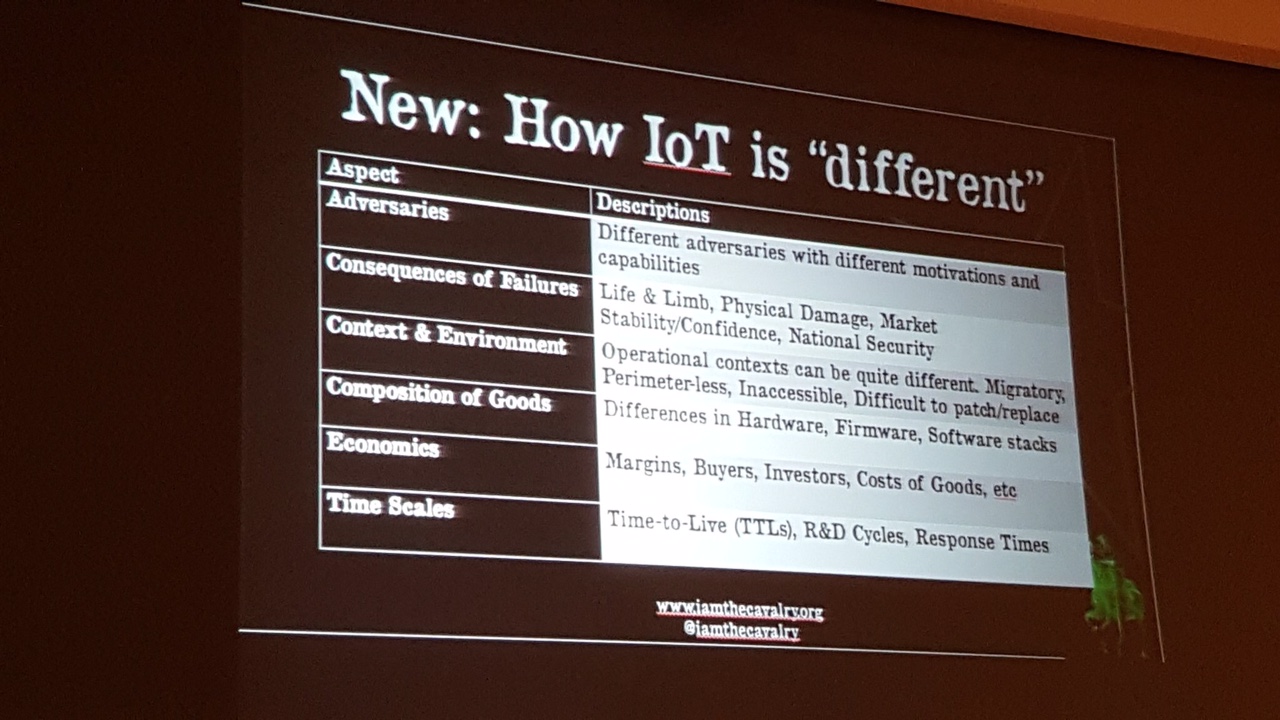

- The IoT context, and risks within it are not homogenous, but brings new risks and adverseries. The risks for manufacturers and consumers and the rest of the public are different, and cannot be easily solved with a one-size-fits-all solution. But we can try.

Concerns I came away with

- If the citizen / customer / individual is to benefit from the IoT trustmark, they must be put first, ahead of companies’ wants.

- If the IoT group controls both the design, assessment to adherence and the definition of success, how objective will it be?

- The group was not sufficiently diverse and as a result, reflects too little on the risks and impact of the lack of diversity in design and effect, and the implications of dataveillance .

- Critical minority thoughts although welcomed, were stripped out from crowdsourced first draft principles in compromise.

- More future thinking should be built-in to be robust over time.

What was missing

There was too little discussion of privacy in perhaps the most important context of IoT – inter connectivity and new adversaries. It’s not only about *your* thing, but things that it speaks to, interacts with, of friends, passersby, the cityscape , and other individual and state actors interested in offense and defense. While we started to discuss it, we did not have the opportunity to discuss sufficiently at depth to be able to get any thinking into applying solutions in the principles.

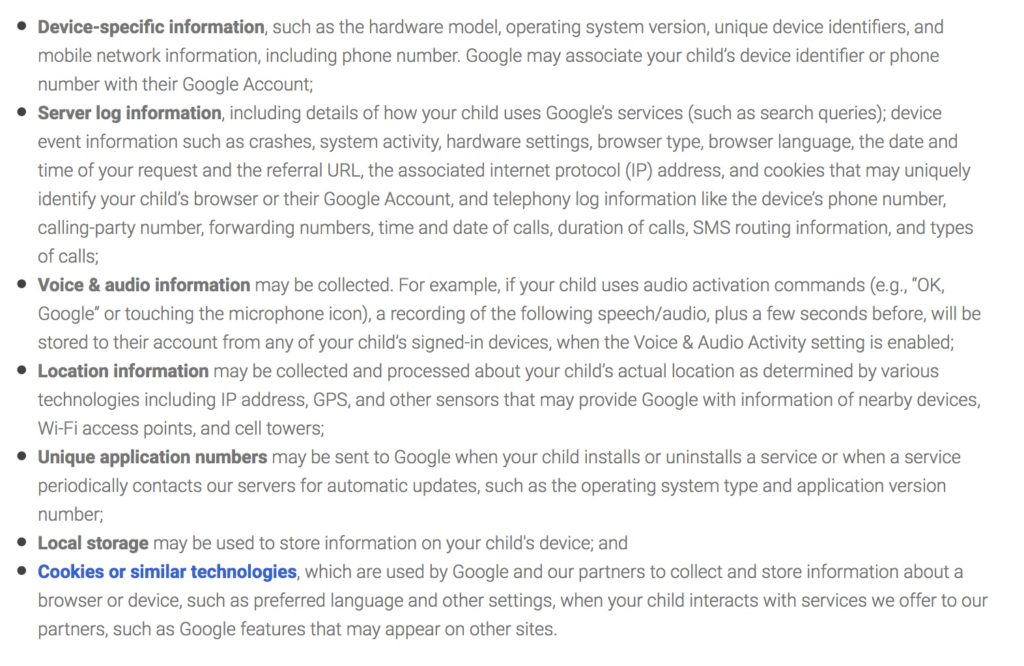

One of the greatest risks that users face is the ubiquitous collection and storage of data about users that reveal detailed, inter-connected patterns of behaviour and our identity and not seeing how that is used by companies behind the scenes.

What we also missed discussing is not what we see as necessary today, but what we can foresee as necessary for the short term future, brainstorming and crowdsourcing horizon scanning for market needs and changing stakeholder wants.

Future thinking

Here’s the areas of future thinking that smart thinking on the IoT mark could consider.

- We are moving towards ever greater requirements to declare identity to use a product or service, to register and log in to use anything at all. How will that change trust in IoT devices?

- Single identity sign-on is becoming ever more imposed, and any attempts for multiple presentation of who I am by choice, and dependent on context, therefore restricted. [not all users want to use the same social media credentials for online shopping, with their child’s school app, and their weekend entertainment]

- Is this imposition what the public wants or what companies sell us as what customers want in the name of convenience? What I believe the public would really want is the choice to do neither.

- There is increasingly no private space or time, at places of work.

- Limitations on private space are encroaching in secret in all public city spaces. How will ‘handoffs’ affect privacy in the IoT?

- Public sector (connected) services are likely to need even more exacting standards than single home services.

- There is too little understanding of the social effects of this connectedness and knowledge created, embedded in design.

- What effects may there be on the perception of the IoT as a whole, if predictive data analysis and complex machine learning and AI hidden in black boxes becomes more commonplace and not every company wants to be or can be open-by-design?

- Ubiquitous collection and storage of data about users that reveal detailed, inter-connected patterns of behaviour and our identity needs greater commitments to disclosure. Where the hand-offs are to other devices, and whatever else is in the surrounding ecosystem, who has responsibility for communicating interaction through privacy notices, or defining legitimate interests, where the data joined up may be much more revealing than stand-alone data in each silo?

- Define with greater clarity the privacy threat models for different groups of stakeholders and address the principles for each.

What would better look like?

The draft privacy principles are a start, but they’re not yet aspirational as I would have hoped. Of course the principles will only be adopted if possible, practical and by those who choose to. But where is the differentiator from what everyone is required to do, and better than the bare minimum? How will you sell this to consumers as new? How would you like your child to be treated?

The wording in these 5 bullet points, is the first crowdsourced starting point.

- The supplier of this product or service MUST be General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliant.

- This product SHALL NOT disclose data to third parties without my knowledge.

- I SHOULD get full access to all the data collected about me.

- I MAY operate this device without connecting to the internet.

- My data SHALL NOT be used for profiling, marketing or advertising without transparent disclosure.

Yes other points that came under security address some of the crossover between privacy and surveillance risks, but there is as yet little substantial that is aspirational to make the IoT mark a real differentiator in terms of privacy. An opportunity remains.

It was that and how young people perceive privacy that I hoped to bring to the table. Because if manufacturers are serious about future success, they cannot ignore today’s children and how they feel. How you treat them today, will shape future purchasers and their purchasing, and there is evidence you are getting it wrong.

The timing is good in that it now also offers the opportunity to promote consistent understanding, and embed the language of GDPR and ePrivacy regulations into consistent and compatible language in policy and practice in the #IoTmark principles.

User rights I would like to see considered

These are some of the points I would think privacy by design would mean. This would better articulate GDPR Article 25 to consumers.

Data sovereignty is a good concept and I believe should be considered for inclusion in explanatory blurb before any agreed privacy principles.

- Goods should by ‘dumb* by default’ until the smart functionality is switched on. [*As our group chair/scribe called it] I would describe this as, “off is the default setting out-of-the-box”.

- Privact by design. Deniability by default. i.e. not only after opt out, but a company should not access the personal or identifying purchase data of anyone who opts out of data collection about their product/service use during the set up process.

- The right to opt out of data collection at a later date while continuing to use services.

- A right to object to the sale or transfer of behavioural data, including to third-party ad networks and absolute opt-in on company transfer of ownership.

- A requirement that advertising should be targeted to content, [user bought fridge A] not through jigsaw data held on users by the company [how user uses fridge A, B, C and related behaviour].

- An absolute rejection of using children’s personal data gathered to target advertising and marketing at children

Background: Starting points before privacy

After a brief recap on 5 years ago, we heard two talks.

The first was a presentation from Bosch. They used the insights from the IoT open definition from 5 years ago in their IoT thinking and embedded it in their brand book. The presenter suggested that in five years time, every fridge Bosch sells will be ‘smart’. And the second was a fascinating presentation, of both EU thinking and the intellectual nudge to think beyond the practical and think what kind of society we want to see using the IoT in future. Hints of hardcore ethics and philosophy that made my brain fizz from Gerald Santucci, soon to retire from the European Commission.

The principles of open sourcing, manufacturing, and sustainable life cycle were debated in the afternoon with intense arguments and clearly knowledgeable participants, including those who were quiet. But while the group had assigned security, and started work on it weeks before, there was no one pre-assigned to privacy. For me, that said something. If they are serious about those who earn the trustmark being better for customers than their competition, then there needs to be greater emphasis on thinking like their customers, and by their customers, and what use the mark will be to customers, not companies. Plan early public engagement and testing into the design of this IoT mark, and make that testing open and diverse.

To that end, I believe it needed to be articulated more strongly, that sustainable public trust is the primary goal of the principles.

- Trust that my device will not become unusable or worthless through updates or lack of them.

- Trust that my device is manufactured safely and ethically and with thought given to end of life and the environment.

- Trust that my source components are of high standards.

- Trust in what data and how that data is gathered and used by the manufacturers.

Fundamental to ‘smart’ devices is their connection to the Internet, and so the last for me, is therefore key to successful public perception and it actually making a difference, beyond the PR value to companies. The value-add must be measured from consumers point of view.

All the openness about design functions and practice improvements, without attempting to change privacy infringing practices, may be wasted effort. Why? Because the perceived benefit of the value of the mark, will be proportionate to what risks it is seen to mitigate.

Why?

Because I assume that you know where your source components come from today. I was shocked to find out not all do and that ‘one degree removed’ is going to be an improvement? Holy cow, I thought. What about regulatory requirements for product safety recalls? These differ of course for different product areas, but I was still surprised. Having worked in global Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) and food industry, semiconductor and optoelectronics, and medical devices it was self-evident for me, that sourcing is rigorous. So that new requirement to know one degree removed, was a suggested minimum. But it might shock consumers to know there is not usually more by default.

Customers also believe they have reasonable expectations of not being screwed by a product update, left with something that does not work because of its computing based components. The public can take vocal, reputation-damaging action when they are let down.

In the last year alone, some of the more notable press stories include a manufacturer denying service, telling customers, “Your unit will be denied server connection,” after a critical product review. Customer support at Jawbone came in for criticism after reported failings. And even Apple has had problems in rolling out major updates.

While these are visible, the full extent of the overreach of company market and product surveillance into our whole lives, not just our living rooms, is yet to become understood by the general population. What will happen when it is?

The Internet of Things is exacerbating the power imbalance between consumers and companies, between government and citizens. As Wendy Grossman wrote recently, in one sense this may make privacy advocates’ jobs easier. It was always hard to explain why “privacy” mattered. Power, people understand.

That public discussion is long overdue. If open principles on IoT devices mean that the signed-up companies differentiate themselves by becoming market leaders in transparency, it will be a great thing. Companies need to offer full disclosure of data use in any privacy notices in clear, plain language under GDPR anyway, but to go beyond that, and offer customers fair presentation of both risks and customer benefits, will not only be a point-of-sales benefit, but potentially improve digital literacy in customers too.

The morning discussion touched quite often on pay-for-privacy models. While product makers may see this as offering a good thing, I strove to bring discussion back to first principles.

Privacy is a human right. There can be no ethical model of discrimination based on any non-consensual invasion of privacy. Privacy is not something I should pay to have. You should not design products that reduce my rights. GDPR requires privacy-by-design and data protection by default. Now is that chance for IoT manufacturers to lead that shift towards higher standards.

We also need a new ethics thinking on acceptable fair use. It won’t change overnight, and perfect may be the enemy of better. But it’s not a battle that companies should think consumers have lost. Human rights and information security should not be on the battlefield at all in the war to win customer loyalty. Now is the time to do better, to be better, demand better for us and in particular, for our children.

Privacy will be a genuine market differentiator

If manufacturers do not want to change their approach to exploiting customer data, they are unlikely to be seen to have changed.

Today feelings that people in US and Europe reflect in surveys are loss of empowerment, feeling helpless, and feeling used. That will shift to shock, resentment, and any change curve will predict, anger.

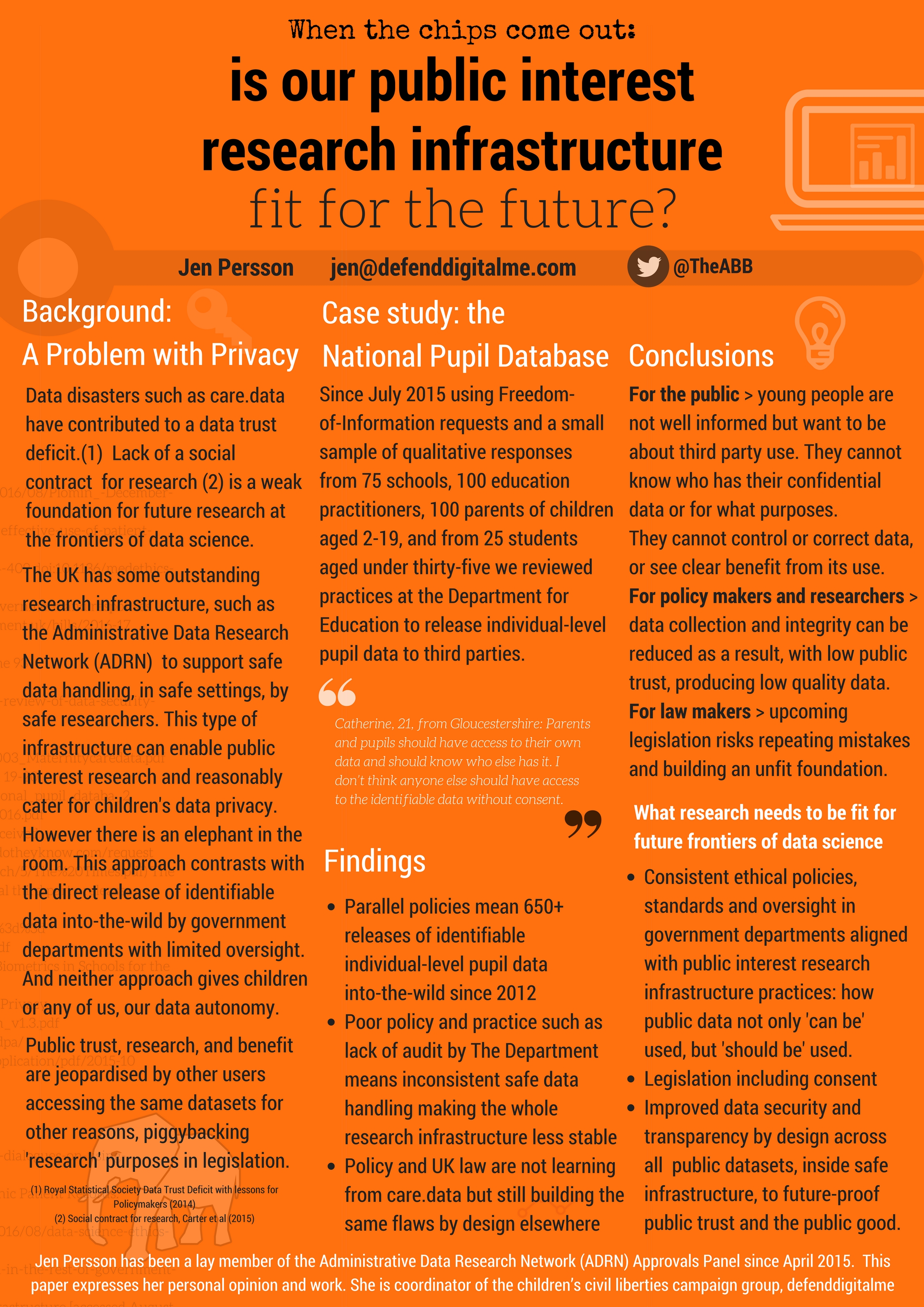

A 2014 survey for the Royal Statistical Society by Ipsos MORI, found that trust in institutions to use data is much lower than trust in them in general.

“The poll of just over two thousand British adults carried out by Ipsos MORI found that the media, internet services such as social media and search engines and telecommunication companies were the least trusted to use personal data appropriately.” [2014, Data trust deficit with lessons for policymakers, Royal Statistical Society]

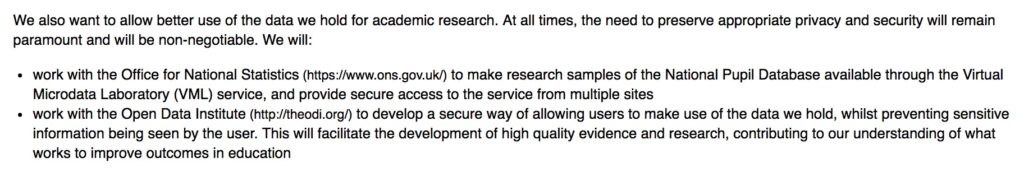

In the British student population, one 2015 survey of university applicants in England, found of 37,000 who responded, the vast majority of UCAS applicants agree that sharing personal data can benefit them and support public benefit research into university admissions, but they want to stay firmly in control. 90% of respondents said they wanted to be asked for their consent before their personal data is provided outside of the admissions service.

In 2010, a multi method model of research with young people aged 14-18, by the Royal Society of Engineering, found that, “despite their openness to social networking, the Facebook generation have real concerns about the privacy of their medical records.” [2010, Privacy and Prejudice, RAE, Wellcome]

When people use privacy settings on Facebook set to maximum, they believe they get privacy, and understand little of what that means behind the scenes.

Are there tools designed by others, like Projects by If licenses, and ways this can be done, that you’re not even considering yet?

What if you don’t do it?

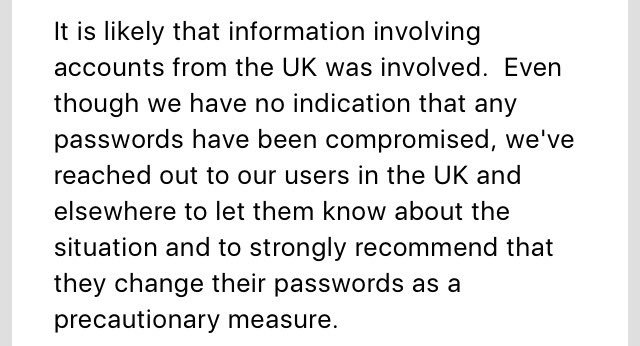

“But do you feel like you have privacy today?” I was asked the question in the afternoon. How do people feel today, and does it matter? Companies exploiting consumer data and getting caught doing things the public don’t expect with their data, has repeatedly damaged consumer trust. Data breaches and lack of information security have damaged consumer trust. Both cause reputational harm. Damage to reputation can harm customer loyalty. Damage to customer loyalty costs sales, profit and upsets the Board.

Where overreach into our living rooms has raised awareness of invasive data collection, we are yet to be able to see and understand the invasion of privacy into our thinking and nudge behaviour, into our perception of the world on social media, the effects on decision making that data analytics is enabling as data shows companies ‘how we think’, granting companies access to human minds in the abstract, even before Facebook is there in the flesh.

Governments want to see how we think too, and is thought crime really that far away using database labels of ‘domestic extremists’ for activists and anti-fracking campaigners, or the growing weight of policy makers attention given to predpol, predictive analytics, the [formerly] Cabinet Office Nudge Unit, Google DeepMind et al?

Had the internet remained decentralized the debate may be different.

I am starting to think of the IoT not as the Internet of Things, but as the Internet of Tracking. If some have their way, it will be the Internet of Thinking.

Considering our centralised Internet of Things model, our personal data from human interactions has become the network infrastructure, and data flows, are controlled by others. Our brains are the new data servers.

In the Internet of Tracking, people become the end nodes, not things.

And it is this where the future users will be so important. Do you understand and plan for factors that will drive push back, and crash of consumer confidence in your products, and take it seriously?

Companies have a choice to act as Empires would – multinationals, joining up even on low levels, disempowering individuals and sucking knowledge and power at the centre. Or they can act as Nation states ensuring citizens keep their sovereignty and control over a selected sense of self.

Look at Brexit. Look at the GE2017. Tell me, what do you see is the direction of travel? Companies can fight it, but will not defeat how people feel. No matter how much they hope ‘nudge’ and predictive analytics might give them this power, the people can take back control.

What might this desire to take-back-control mean for future consumer models? The afternoon discussion whilst intense, reached fairly simplistic concluding statements on privacy. We could have done with at least another hour.

Some in the group were frustrated “we seem to be going backwards” in current approaches to privacy and with GDPR.

But if the current legislation is reactive because companies have misbehaved, how will that be rectified for future? The challenge in the IoT both in terms of security and privacy, AND in terms of public perception and reputation management, is that you are dependent on the behaviours of the network, and those around you. Good and bad. And bad practices by one, can endanger others, in all senses.

If you believe that is going back to reclaim a growing sense of citizens’ rights, rather than accepting companies have the outsourced power to control the rights of others, that may be true.

There was a first principle asked whether any element on privacy was needed at all, if the text was simply to state, that the supplier of this product or service must be General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliant. The GDPR was years in the making after all. Does it matter more in the IoT and in what ways? The room tended, understandably, to talk about it from the company perspective. “We can’t” “won’t” “that would stop us from XYZ.” Privacy would however be better addressed from the personal point of view.

What do people want?

From the company point of view, the language is different and holds clues. Openness, control, and user choice and pay for privacy are not the same thing as the basic human right to be left alone. Afternoon discussion reminded me of the 2014 WAPO article, discussing Mark Zuckerberg’s theory of privacy and a Palo Alto meeting at Facebook:

“Not one person ever uttered the word “privacy” in their responses to us. Instead, they talked about “user control” or “user options” or promoted the “openness of the platform.” It was as if a memo had been circulated that morning instructing them never to use the word “privacy.””

In the afternoon working group on privacy, there was robust discussion whether we had consensus on what privacy even means. Words like autonomy, control, and choice came up a lot. But it was only a beginning. There is opportunity for better. An academic voice raised the concept of sovereignty with which I agreed, but how and where to fit it into wording, which is at once both minimal and applied, and under a scribe who appeared frustrated and wanted a completely different approach from what he heard across the group, meant it was left out.

This group do care about privacy. But I wasn’t convinced that the room cared in the way that the public as a whole does, but rather only as consumers and customers do. But IoT products will affect potentially everyone, even those who do not buy your stuff. Everyone in that room, agreed on one thing. The status quo is not good enough. What we did not agree on, was why, and what was the minimum change needed to make a enough of a difference that matters.

I share the deep concerns of many child rights academics who see the harm that efforts to avoid restrictions Article 8 the GDPR will impose. It is likely to be damaging for children’s right to access information, be discriminatory according to parents’ prejudices or socio-economic status, and ‘cheating’ – requiring secrecy rather than privacy, in attempts to hide or work round the stringent system.

In ‘The Class’ the research showed, ” teachers and young people have a lot invested in keeping their spheres of interest and identity separate, under their autonomous control, and away from the scrutiny of each other.” [2016, Livingstone and Sefton-Green, p235]

Employers require staff use devices with single sign including web and activity tracking and monitoring software. Employee personal data and employment data are blended. Who owns that data, what rights will employees have to refuse what they see as excessive, and is it manageable given the power imbalance between employer and employee?

What is this doing in the classroom and boardroom for stress, anxiety, performance and system and social avoidance strategies?

A desire for convenience creates shortcuts, and these are often met using systems that require a sign-on through the platforms giants: Google, Facebook, Twitter, et al. But we are kept in the dark how by using these platforms, that gives access to them, and the companies, to see how our online and offline activity is all joined up.

Any illusion of privacy we maintain, we discussed, is not choice or control if based on ignorance, and backlash against companies lack of efforts to ensure disclosure and understanding is growing.

“The lack of accountability isn’t just troubling from a philosophical perspective. It’s dangerous in a political climate where people are pushing back at the very idea of globalization. There’s no industry more globalized than tech, and no industry more vulnerable to a potential backlash.”

[Maciej Ceglowski, Notes from an Emergency, talk at re.publica]

Why do users need you to know about them?

If your connected *thing* requires registration, why does it? How about a commitment to not forcing one of these registration methods or indeed any at all? Social Media Research by Pew Research in 2016 found that 56% of smartphone owners ages 18 to 29 use auto-delete apps, more than four times the share among those 30-49 (13%) and six times the share among those 50 or older (9%).

Does that tell us anything about the demographics of data retention preferences?

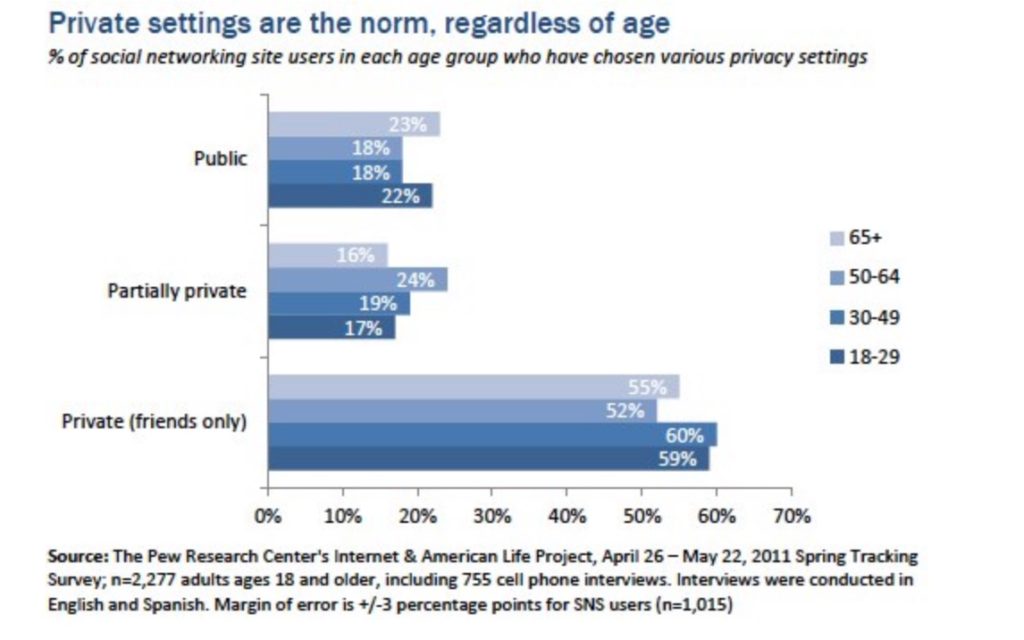

In 2012, they suggested social media has changed the public discussion about managing “privacy” online. When asked, people say that privacy is important to them; when observed, people’s actions seem to suggest otherwise.

Does that tell us anything about how well companies communicate to consumers how their data is used and what rights they have?

There is also data with strong indications about how women act to protect their privacy more but when it comes to basic privacy settings, users of all ages are equally likely to choose a private, semi-private or public setting for their profile. There are no significant variations across age groups in the US sample.

Now think about why that matters for the IoT? I wonder who makes the bulk of purchasing decsions about household white goods for example and has Bosch factored that into their smart-fridges-only decision?

Do you *need* to know who the user is? Can the smart user choose to stay anonymous at all?

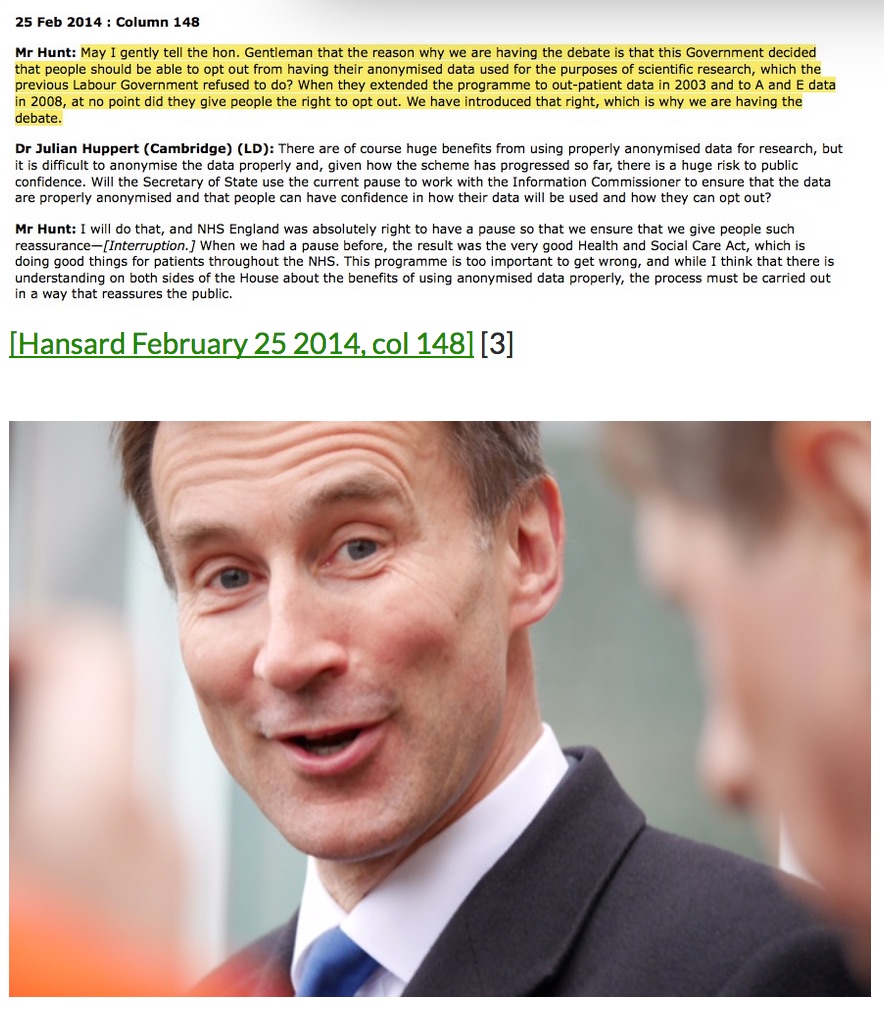

The day’s morning challenge was to attend more than one interesting discussion happening at the same time. As invariably happens, the session notes and quotes are always out of context and can’t possibly capture everything, no matter how amazing the volunteer (with thanks!). But here are some of the discussion points from the session on the body and health devices, the home, and privacy. It also included a discussion on racial discrimination, algorithmic bias, and the reasons why care.data failed patients and failed as a programme. We had lengthy discussion on ethics and privacy: smart meters, objections to models of price discrimination, and why pay-for-privacy harms the poor by design.

Smart meter data can track the use of unique appliances inside a person’s home and intimate patterns of behaviour. Information about our consumption of power, what and when every day, reveals personal details about everyday lives, our interactions with others, and personal habits.

Why should company convenience come above the consumer’s? Why should government powers, trump personal rights?

Smart meter is among the knowledge that government is exploiting, without consent, to discover a whole range of issues, including ensuring that “Troubled Families are identified”. Knowing how dodgy some of the school behaviour data might be, that helps define who is “troubled” there is a real question here, is this sound data science? How are errors identified? What about privacy? It’s not your policy, but if it is your product, what are your responsibilities?

If companies do not respect children’s rights, you’d better shape up to be GDPR compliant

For children and young people, more vulnerable to nudge, and while developing their sense of self can involve forming, and questioning their identity, these influences need oversight or be avoided.

In terms of GDPR, providers are going to pay particular attention to Article 8 ‘information society services’ and parental consent, Article 17 on profiling, and rights to restriction of processing (19) right to erasure in recital 65 and rights to portability. (20) However, they may need to simply reassess their exploitation of children and young people’s personal data and behavioural data. Article 57 requires special attention to be paid by regulators to activities specifically targeted at children, as ‘vulnerable natural persons’ of recital 75.

Human Rights, regulations and conventions overlap in similar principles that demand respect for a child, and right to be let alone:

(a) The development of the child ‘s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential;

(b) The development of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and for the principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations.

A weakness of the GDPR is that it allows derogation on age and will create inequality and inconsistency for children as a result. By comparison Article one of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) defines who is to be considered a “child” for the purposes of the CRC, and states that: “For the purposes of the present Convention, a child means every human being below the age of eighteen years unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier.”<

Article two of the CRC says that States Parties shall respect and ensure the rights set forth in the present Convention to each child within their jurisdiction without discrimination of any kind.

CRC Article 16 says that no child shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her honour and reputation.

Article 8 CRC requires respect for the right of the child to preserve his or her identity […] without unlawful interference.

Article 12 CRC demands States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.

That stands in potential conflict with GDPR article 8. There is much on GDPR on derogations by country, and or children, still to be set.

What next for our data in the wild

Hosting the event at the zoo offered added animals, and during a lunch tour we got out on a tour, kindly hosted by a fellow participant. We learned how smart technology was embedded in some of the animal enclosures, and work on temperature sensors with penguins for example. I love tigers, so it was a bonus that we got to see such beautiful and powerful animals up close, if a little sad for their circumstances and as a general basic principle, seeing big animals caged as opposed to in-the-wild.

Freedom is a common desire in all animals. Physical, mental, and freedom from control by others.

I think any manufacturer that underestimates this element of human instinct is ignoring the ‘hidden dragon’ that some think is a myth. Privacy is not dead. It is not extinct, or even unlike the beautiful tigers, endangered. Privacy in the IoT at its most basic, is the right to control our purchasing power. The ultimate people power waiting to be sprung. Truly a crouching tiger. People object to being used and if companies continue to do so without full disclosure, they do so at their peril. Companies seem all-powerful in the battle for privacy, but they are not. Even insurers and data brokers must be fair and lawful, and it is for regulators to ensure that practices meet the law.

When consumers realise our data, our purchasing power has the potential to control, not be controlled, that balance will shift.

“Paper tigers” are superficially powerful but are prone to overextension that leads to sudden collapse. If that happens to the superficially powerful companies that choose unethical and bad practice, as a result of better data privacy and data ethics, then bring it on.

I hope that the IoT mark can champion best practices and make a difference to benefit everyone.

While the companies involved in its design may be interested in consumers, I believe it could be better for everyone, done well. The great thing about the efforts into an #IoTmark is that it is a collective effort to improve the whole ecosystem.

I hope more companies will realise their privacy rights and ethical responsibility in the world to all people, including those interested in just being, those who want to be let alone, and not just those buying.

“If a cat is called a tiger it can easily be dismissed as a paper tiger; the question remains however why one was so scared of the cat in the first place.”

Further reading: Networks of Control – A Report on Corporate Surveillance, Digital Tracking, Big Data & Privacy by Wolfie Christl and Sarah Spiekermann