A slightly longer version of a talk I gave at the launch event of the OMDDAC Data-Driven Responses to COVID-19: Lessons Learned report on October 13, 2021. I was asked to respond to the findings presented on Young People, Covid-19 and Data-Driven Decision-Making by Dr Claire Bessant at Northumbria Law School.

[ ] indicates text I omitted for reasons of time, on the day.

Their final report is now available to download from the website.

You can also watch the full event here via YouTube. The part on young people presented by Claire and that I follow, is at the start.

—————————————————–

I’m really pleased to congratulate Claire and her colleagues today at OMDDAC and hope that policy makers will recognise the value of this work and it will influence change.

I will reiterate three things they found or included in their work.

- Young people want to be heard.

- Young people’s views on data and trust, include concerns about conflated data purposes

and

3. The concept of being, “data driven under COVID conditions”.

This OMDDAC work together with Investing in Children, is very timely as a rapid response, but I think it is also important to set it in context, and recognize that some of its significance is that it reflects a continuum of similar findings over time, largely unaffected by the pandemic.

Claire’s work comprehensively backs up the consistent findings of over ten years of public engagement, including with young people.

The 2010 study with young people conducted by The Royal Academy of Engineering supported by three Research Councils and Wellcome, discussed attitudes towards the use of medical records and concluded: These questions and concerns must be addressed by policy makers, regulators, developers and engineers before progressing with the design, and implementation of record keeping systems and the linking of any databases.

In 2014, the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee in their report, Responsible Use of Data, said the Government has a clear responsibility to explain to the public how personal data is being used.

The same Committee’s Big Data Dilemma 2015-16 report, (p9) concluded “data (some collected many years before and no longer with a clear consent trail) […] is unsatisfactory left unaddressed by Government and without a clear public-policy position.”

Or see

2014, The Royal Statistical Society and Ipsos Mori work on the data trust deficit with lessons for policymakers, 2019 DotEveryone’s work on Public Attitudes or the 2020 The ICO Annual Track survey results.

There is also a growing body of literature to demonstrate what the implications are being a ‘data driven’ society, for the datafied child, as described by Deborah Lupton and Ben Williamson in their own research in 2017.

[This year our own work with young people, published in our report on data metaphors “the words we use in data policy”, found that young people want institutions to stop treating data about them as a commodity and start respecting data as extracts from the stories of their lives.]

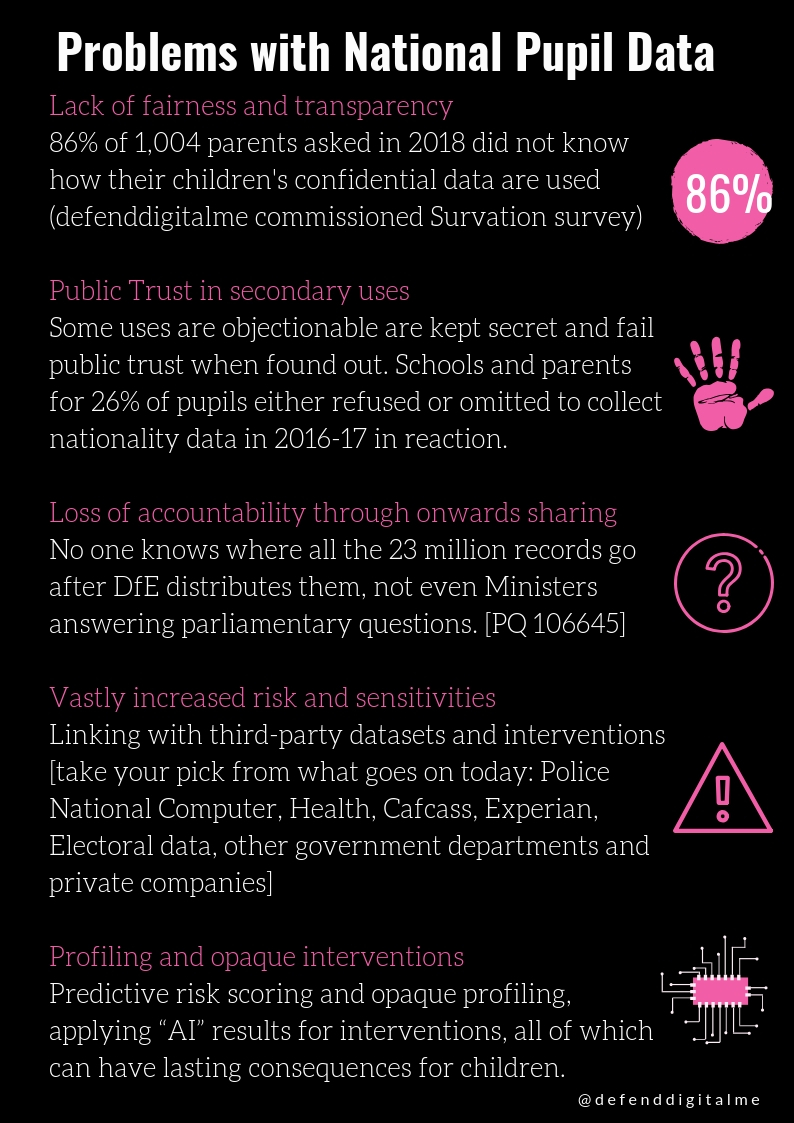

The UK government and policy makers, are simply ignoring the inconvenient truth that legislation and governance frameworks such as the UN General Comment no 25 on Children in the Digital Environment, that exist today, demand people know what is done with data about them, and it must be applied to address children’s right to be heard and to enable them to exercise their data rights.

The public perceptions study within this new OMDDAC work, shows that it’s not only the views of children and young people that are being ignored, but adults too.

And perhaps it is worth reflecting here, that often people don’t tend to think about all this in terms of data rights and data protection, but rather human rights and protections for the human being from the use of data that gives other people power over our lives.

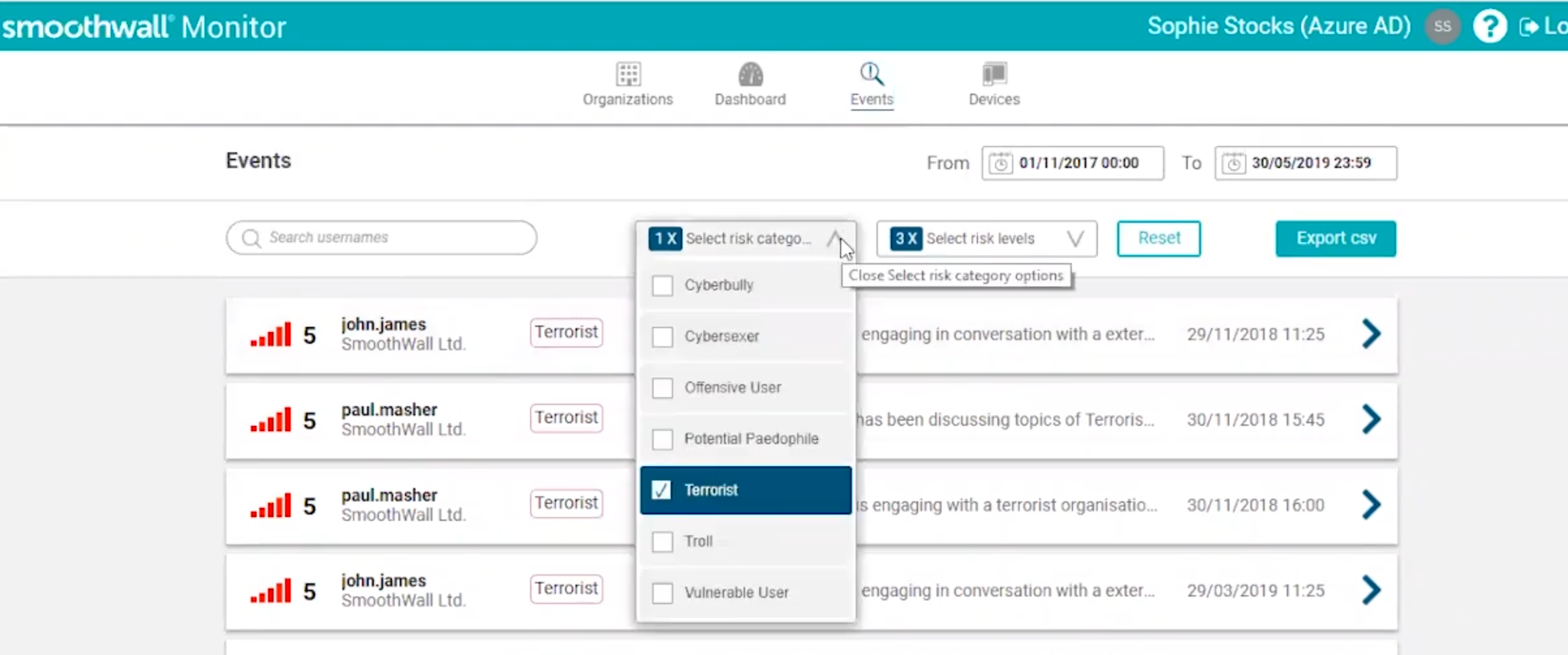

This project, found young people’s trust in use of their confidential personal data was affected by understanding who would use the data and why, and how people will be protected from prejudice and discrimination.

We could build easy-reporting mechanisms at public points of contact with state institutions; in education, in social care, in welfare and policing, to produce reports on demand of the information you hold about me and enable corrections. It would benefit institutions by having more accurate data, and make them more trustworthy if people can see here’s what you hold on me and here’s what you did with it.

Instead, we’re going in the opposite direction. New government proposals suggest making that process harder, by charging for Subject Access Requests.

This research shows that current policy is not what young people want. People want the ability to choose between granular levels of control in the data that is being shared. They value having autonomy and control, knowing who will have access, maintaining records accuracy, how people will be kept informed of changes, who will maintain and regulate the database, data security, anonymisation, and to have their views listened to.

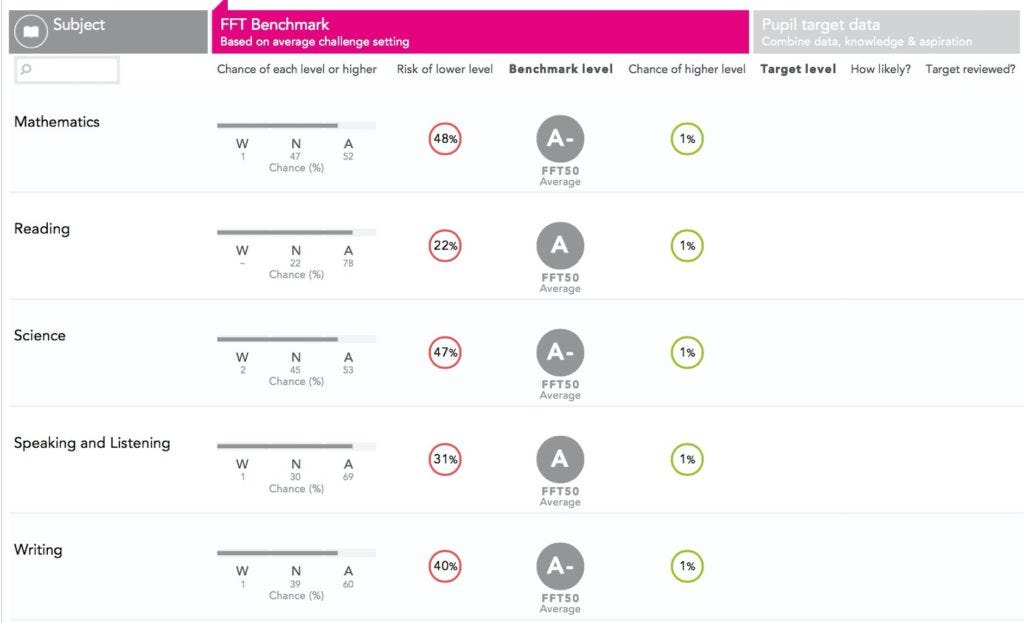

Young people also fear the power of data to speak for them, that the data about them are taken at face value, listened to by those in authority more than the child in their own voice.

What do these findings mean for public policy? Without respect for what people want; for the fundamental human rights and freedoms for all, there is no social license for data policies.

Whether it’s confidential GP records or the school census expansion in 2016, when public trust collapses so does your data collection.

Yet the government stubbornly refuses to learn and seems to believe it’s all a communications issue, a bit like the ‘Yes Minister’ English approach to foreigners when they don’t understand: just shout louder.

No, this research shows data policy failures are not fixed by, “communicate the benefits”.

Nor is it fixed by changing Data Protection law. As a comment in the report says, UK data protection law offers a “how-to” not a “don’t-do”.

Data protection law is designed to be enabling of data flows. But that can mean that when state data processing rightly often avoids using the lawful basis of consent in data protection terms, the data use is not consensual.

[For the sake of time, I didn’t include this thought in the next two paragraphs in the talk, but I think it is important to mention that in our own work we find that this contradiction is not lost on young people. — Against the backdrop of the efforts after the MeToo movement and lots said by Ministers in Education and at the DCMS about the Everyone’s Invited work earlier this year to champion consent in relationships, sex and health education (RSHE) curriculum; adults in authority keep saying consent matters, but don’t demonstrate it, and when it comes to data, use people’s data in ways they do not want.

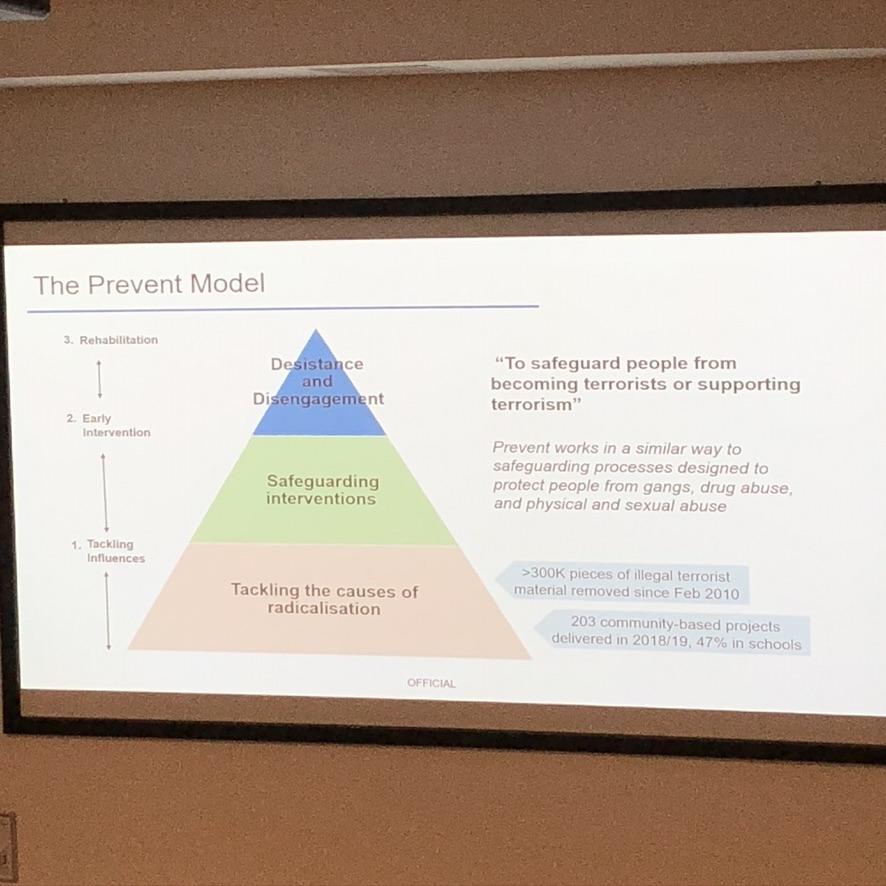

The report picks up that young people, and disproportionately those communities that experience harm from authorities, mistrust data sharing with the police. This is now set against the backdrop of not only the recent, Wayne Couzens case, but a series of very public misuses of police power, including COVID powers.]

The data powers used, “Under COVID conditions” are now being used as a cover for the attack on data protections in the future. The DCMS consultation on changing UK Data Protection law, open until November 19th, suggests that similarly reduced protections on data distribution in the emergency, should become the norm. While DP law is written expressly to permit things that are out of the ordinary in extraordinary circumstances, they are limited in time. The government is proposing that some things that were found convenient to do under COVID, now become commonplace.

But it includes things such as removing Article 22 from the UK GDPR with its protections for people in processes involving automated decision making.

Young people were those who felt first hand the risks and harms of those processes in the summer of 2020, and the “mutant algorithm” is something this Observatory Report work also addressed in their research. Again, it found young people felt left out of those decisions about them despite being the group that would feel its negative effects.

[Data protection law may be enabling increased lawful data distribution across the public sector, but it is not offering people, including young people, the protections they expect of their human right to privacy. We are on a dangerous trajectory for public interest research and for society, if the “new direction” this government goes in, for data and digital policy and practice, goes against prevailing public attitudes and undermines fundamental human rights and freedoms.]

The risks and benefits of the power obtained from the use of admin data are felt disproportionately across different communities including children, who are not a one size fits all, homogenous group.

[While views across groups will differ — and we must be careful to understand any popular context at any point in time on a single issue and unconscious bias in and between groups — policy must recognise where there are consistent findings across this research with that which has gone before it. There are red lines about data re-uses, especially on conflated purposes using the same data once collected by different people, like commercial re-use or sharing (health) data with police.]

The golden thread that runs through time and across different sectors’ data use, are the legal frameworks underpinned by democratic mandates, that uphold our human rights.

I hope the powers-at-be in the DCMS consultation, and wider policy makers in data and digital policy, take this work seriously and not only listen, but act on its recommendations.

2024 updates: opening paragraph edited to add current links.

A chapter written by Rachel Allsopp and Claire bessant discussing OMDDAC’s research with children will also be published on 21st May 2024 in Governance, democracy and ethics in crisis-decision-making: The pandemic and beyond (Manchester University Press) as part of its Pandemic and Beyond series https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526180049/ and an article discussing the research in the open access European Journal of Law and Technology is available here https://www.ejlt.org/index.php/ejlt/article/view/872.