Atlas, the Boston Dynamics created robot, won hearts and minds this week as it stoically survived man being mean. Our collective human response was an emotional defence of the machine, and criticism of its unfair treatment by its tester.

Some on Twitter recalled the incident of Lord of The Flies style bullying by children in Japan that led the programmers to create an algorithm for ‘abuse avoidance’.

The concepts of fairness and of decision making algorithms for ‘abuse avoidance’ are interesting from perspectives of data mining, AI and the wider access to and use of tech in general, and in health specifically.

If the decision to avoid abuse can be taken out of an individual’s human hands and are based on unfathomable amounts of big data, where are its limits applied to human behaviour and activity?

When it is decided that an individual’s decision making capability is impaired or has been forfeited their consent may be revoked in their best interest.

Who has oversight of the boundaries of what is acceptable for one person, or for an organisation, to decide what is in someone else’s best interest, or indeed, the public interest?

Where these boundaries overlap – personal abuse avoidance, individual best interest and the public interest – and how society manage them, with what oversight, is yet to be widely debated.

The public will shortly be given the opportunity to respond to plans for the expansion of administrative datasharing in England through consultation.

We must get involved and it must be the start of a debate and dialogue not simply a tick-box to a done-deal, if data derived from us are to be used as a platform for future to “achieve great results for the NHS and everyone who depends on it.”

Administering applied “abuse avoidance” and Restraining Abilities

Administrative uses and secondary research using the public’s personal data are applied not only in health, but across the board of public bodies, including big plans for tech in the justice system.

An example in the news this week of applied tech and its restraint on human behaviour was ankle monitors. While one type was abandoned by the MOJ at a cost of £23m on the same day more funding for transdermal tags was announced in London.

The use of this technology as a monitoring tool, should not of itself be a punishment. It is said compliance is not intended to affect the dignity of individuals who are being monitored, but through the collection of personal and health data will ensure the deprivation of alcohol – avoiding its abuse for a person’s own good and in the public interest. Is it fair?

Abstinence orders might be applied to those convicted of crimes such as assault, being drunk and disorderly and drunk driving.

We’re yet to see much discussion of how these varying degrees of integration of tech with the human body, and human enhancement will happen through robot elements in our human lives.

How will the boundaries of what is possible and desirable be determined and by whom with what oversight?

What else might be considered as harmful as alcohol to individuals and to society? Drugs? Nictotine? Excess sugar?

As we wonder about the ethics of how humanoids will act and the aesthetics of how human they look, I wonder how humane are we being, in all our ‘public’ tech design and deployment?

Umberto Eco who died on Friday wrote in ‘The birth of ethics’ that there are universal ideas on constraints, effectively that people should not harm other people, through deprivation, restrictions or psychological torture. And that we should not impose anything on others that “diminishes or stifles our capacity to think.”

How will we as a society collectively agree what that should look like, how far some can impose on others, without consent?

Enhancing the Boundaries of Being Human

Technology might be used to impose bodily boundaries on some people, but tech can also be used for the enhancement of others. Antonio Santos retweeted this week, the brilliant Angel Giuffria’s arm.

Got to talk to this little dude in Austin at #BDYHAX about being a #cyborg#amputeehttps://t.co/azKzwVkTGxpic.twitter.com/LHUFxNfzth

— Angel Giuffria (@aannggeellll) February 27, 2016

While the technology in this case is literally hands-on in its application, increasingly it is not the technology itself but the data that it creates or captures which enables action through data-based decision making.

Robots that are tiny may be given big responsibilities to monitor and report massive amounts of data. What if we could swallow them?

Data if analysed and understood, become knowledge.

Knowledge can be used to inform decisions and take action.

So where are the boundaries of what data may be extracted, information collated, and applied as individual interventions?

Defining the Boundaries of “in the Public Interest”

Where are boundaries of what data may be created, stored, and linked to create a detailed picture about us as individuals, if the purpose is determined to be in the public interest?

Who decides which purposes are in the public interest? What qualifies as research purposes? Who qualifies as meeting the criteria of ‘researcher’?

How far can research and interventions go without consent?

Should security services and law enforcement agencies always be entitled to get access to individuals’ data ‘in the public interest’?

That’s something Apple is currently testing in the US.

Should research bodies always be entitled to get access to individuals’ data ‘in the public interest’?

That’s something care.data tried and failed to assume the public supported and has yet to re-test. Impossible before respecting the opt out that was promised over two years ago in March 2014.

The question how much data research bodies may be ‘entitled to’ will be tested again in the datasharing consultation in the UK.

How data already gathered are used in research may be used differently from it is when we consent to its use at colllection. How this changes over time and its potential for scope creep is seen in Education. Pupil data has gone from passive collection of name to giving it out to third parties, to use in national surveys, so far.

And what of the future?

Where is the boundary between access and use of data not in enforcement of acts already committed but in their prediction and prevention?

If you believe there should be an assumption of law enforcement access to data when data are used for prediction and prevention, what about health?

Should there be any difference between researchers’ access to data when data are used for past analysis and for use in prediction?

If ethics define the boundary between what is acceptable and where actions by one person may impose something on another that “diminishes or stifles our capacity to think” – that takes away our decision making capacity – that nudges behaviour, or acts on behaviour that has not yet happened, who decides what is ethical?

How does a public that is poorly informed about current data practices, become well enough informed to participate in the debate of how data management should be designed today for their future?

How Deeply Mined should our Personal Data be?

The application of technology, non-specific but not yet AI, was also announced this week in the Google DeepMind work in the NHS.

Its first key launch app co-founder provided a report that established the operating framework for the Behavioural Insights Team established by Prime Minister David Cameron.

A number of highly respected public figures have been engaged to act in the public interest as unpaid Independent Reviewers of Google DeepMind Health. It will be interesting to see what their role is and how transparent its workings and public engagement will be.

The recent consultation on the NHS gave overwhelming feedback that the public does not support the direction of current NHS change. Even having removed all responses associated with ‘lefty’ campaigns, concerns listed on page 11, are consistent including a request the Government “should end further involvement of the private sector in healthcare”. It appears from the response that this engagement exercise will feed little into practice.

The strength of feeling should however be a clear message to new projects that people are passionate that equal access to healthcare for all matters and that the public wants to be informed and have their voices heard.

How will public involvement be ensured as complexity increases in these healthcare add-ons and changing technology?

Will Google DeepMind pave the way to a new approach to health research? A combination of ‘nudge’ behavioural insights, advanced neural networks, Big Data and technology is powerful. How will that power be used?

I was recently told that if new research is not pushing the boundaries of what is possible and permissible then it may not be worth doing, as it’s probably been done before.

Should anything that is new that becomes possible be realised?

I wonder how the balance will be weighted in requests for patient data and their application, in such a high profile project.

Will NHS Research Ethics Committees turn down research proposals in-house in hospitals that benefit the institution or advance their reputation, or the HSCIC, ever feel able to say no to data use by Google DeepMind?

Ethics committees safeguard the rights, safety, dignity and well-being of research participants, independently of research sponsors whereas these representatives are not all independent of commercial supporters. And it has not claimed it’s trying to be an ethics panel. But oversight is certainly needed.

The boundaries of ownership between what is seen to benefit commercial and state in modern health investment is perhaps more than blurred to an untrained eye. Genomics England – the government’s flagship programme giving commercial access to the genome of 100K people – stockholding companies, data analytics companies, genome analytic companies, genome collection, and human tissue research, commercial and academic research, often share directors, working partnerships and funders. That’s perhaps unsurprising given such a specialist small world.

It’s exciting to think of the possibilities if, “through a focus on patient outcomes, effective oversight, and the highest ethical principles, we can achieve great results for the NHS and everyone who depends on it.”

Where will an ageing society go, if medics can successfully treat more cancer for example? What diseases will be prioritised and others left behind in what is economically most viable to prevent? How much investment will be made in diseases of the poor or in countries where governments cannot afford to fund programmes?

What will we die from instead? What happens when some causes of ‘preventative death’ are deemed more socially acceptable than others? Where might prevention become socially enforced through nudging behaviour into new socially acceptable or ethical norms?

Don’t be Evil

Given the leading edge of the company and its curiosity-by-design to see how far “can we” will reach, “don’t be evil” may be very important. But “be good” might be better. Where is that boundary?

The boundaries of what ‘being human’ means and how Big Data will decide and influence that, are unclear and changing. How will the law and regulation keep up and society be engaged in support?

Data principles such as fairness, keeping data accurate, complete and up-to-date and ensuring data are not excessive retained for no longer than necessary for the purpose are being widely ignored or exempted under the banner of ‘research’.

Can data use retain a principled approach despite this and if we accept commercial users, profit making based on public data, will those principles from academic research remain in practice?

Exempt from the obligation to give a copy of personal data to an individual on request if data are for ‘research’ purposes, data about us and our children, are extracted and stored ‘without us’. Forever. That means in a future that we cannot see, but Google DeepMind among others, is designing.

Lay understanding, and that of many climical professionals is likely to be left far behind if advanced technologies and use of big data decision-making algorithms are hidden in black boxes.

Public transparency of the use of our data and future planned purposes are needed to create trust that these purposes are wise.

Data are increasingly linked and more valuable when identifiable.

Any organisation that wants to future-proof its reputational risk will make sure data collection and use today is with consent, since future outcomes derived are likely to be in interventions for individuals or society. Catching up consent will be hard unless designed in now.

A Dialogue on the Boundaries of Being Human and Big Data

Where the commercial, personal, and public interests are blurred, the highest ethical principles are going to be needed to ensure ‘abuse avoidance’ in the use of new technology, in increased data linkage and resultant data use in research of many different kinds.

How we as a society achieve the benefits of tech and datasharing and where its boundaries lie in “the public interest” needs public debate to co-design the direction we collectively want to partake in.

Once that is over, change needs supported by a method of oversight that is responsive to new technology, data use, and its challenges.

What a channel for ongoing public dialogue, challenge and potentially recourse might look like, should be part of that debate.

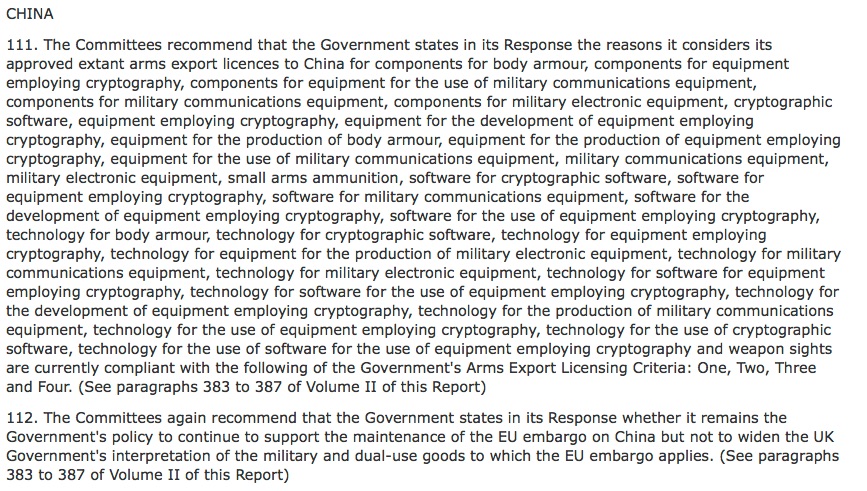

![Wearables: patients will ‘essentially manage their data as they wish’. What will this mean for diagnostics, treatment and research and why should we care? [#NHSWDP 3]](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/FullSizeRender1-672x372.jpg)