Based on a talk prepared for an event in parliament, hosted by Connected By Data and chaired by Lord Tim Clement-Jones, focusing on the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill, on Monday 5th December 17:00-19:00. “Ensuring people have a say in future data governance”.

Some reflections on Data in Schools (a) general issues; (b) the direction of travel the Government going in and; (c) what should happen, in the Bill or more widely.

Following Professor Sonia Livingstone who focussed primarily on the issues connected with edTech, I focussed on the historical and political context of where we are today, on ‘having a say’ in education data and its processing in, across, and out of, the public sector.

What should be different with or without this Bill?

Since I ran out of time yesterday I’m going to put first what I didn’t get around to: the key conclusions that point to what is possible with or without new Data Protection law. We should be better at enabling the realisation of existing data rights in the education sector today. The state and extended services could build tools for schools to help them act as controllers and for children to realise rights like a PEGE (a personalized exam grade explainer to show exam candidates what data was used to calculate their grade and how), Data usage reports should be made available at least annually from schools to help families understand what data about their children has gone where; and methods that enable the child or family to correct errors or express a Right to Object should be mandatory in schools’ information management systems. Supplier standards on accuracy and error notifications should be made explicit and statutory, and supplier service level agreements affected by repeated failures.

Where is the change needed to create the social license for today’s practice, even before we look to the future?

“Ensuring people have a say in future data governance”. There has been a lot of asking lots of people for a say in the last decade. When asked, the majority of people generally want the same things—both those who are willing and less willing to have personal data about them re-used that was collected for administrative purposes in the public sector—to be told what data is collected for and how it is used, opt-in to re-use, to be able to control distribution, and protections for redress and against misuse strengthened in legislation.

Read Doteveryone’s public attitudes work. Or the Ipsos MORI polls or work by Wellcome. (see below). Or even the care.data summaries.

The red lines in the “Dialogues on Data” report from workshops carried out across different devolved regions of the UK for the 2013 ADRN remain valid today (about the reuse of deidentified linked public admin datasets by qualified researchers in safe settings not even raw identifying data), in particular with relation to:

- Creating large databases containing many variables/data from a large number of public sector sources

- Allowing administrative data to be linked with business data

- Linking of passively collected administrative data, in particular geo-location data

“All of the above were seen as having potential privacy implications or allowing the possibility of reidentification of individuals within datasets. The other ‘red-line’ for some participants was allowing researchers for private companies to access data, either to deliver a public service or in order to make profit. Trust in private companies’ motivations were low.”

Much of this reflects what children and young people say as well. RAENG (2010) carried out engagement work with children on health data Privacy and Prejudice: young people’s views on the development and use of Electronic Patient Records (911.18 KB). They are very clear about wanting to keep their medical details under their own control and away from the ‘wrong hands’ which includes potential employers, commercial companies and parents.

Our own engagement work with a youth group aged 14-25 at a small scale was published in 2020 in our work, The Words We Use in Data Policy: Putting People Back in the Picture, and reflected what the Office for the Regulation of National Statistics went to publish in their own 2022 report, Visibility, Vulnerability and Voice (as a framework to explore whether the current statistics are helping society to understand the experiences of children and young people in all aspects of their lives). Young people worry about misrepresentation, about the data being used in place of conversations about them to take decisions that affect their lives, and about the power imbalance it creates without practical routes for complaint or redress. We all agree children’s voice is left out of the debate on data about them.

Parents are left out too. Defenddigitalme commissioned a parental survey via Survation (2018) under 50% felt they had sufficient control of their child’s digital footprint, and 2/3rds had not heard of the National Pupil Database or its commercial reuse.

So why is it that the public voice, loud and clear, is ignored in public policy and ignored in the drafting of the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill?

When it comes to education, debate should start with children’s and family rights in education, and education policy, not about data produced as its by-product.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights Article 26 grafts a parent’s right onto child’s right to education, to choose the type of that education and it defines the purposes of education.

Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace. Becoming a set of data points for product development or research is not the reason children go to school and hand over their personal details in the admissions process at all.

The State of the current landscape

To realise change, we must accept the current state of play and current practice. This includes a backdrop of trying to manage data well in the perilous state of public infrastructure, shrinking legal services and legal aid for children, ever-shrinking educational services in and beyond mainstream education, staff shortages and retention issues, and the lack of ongoing training or suitable and sustainable IT infrastructure for staff and learners.

Current institutional guidance and national data policy in the field is poor and takes the perspective of the educational setting but not the person.

- Department for Education (DfE) 2018 guidance on data protection and edTech is wrong on consent and an online services ‘age of consent’

- Statutory Guidance is woeful on safety tech (pp36-37) and its rights infringements but also from a practical perspective as highlighted in the case of Frankie Thomas where it wasn’t working; which is why our lawyers have written to the Department and we are considering challenging the statutory guidance more formally

Three key issues are problems from top-down and across systems:

- Data repurposing i.e. SATS Key Stage 2 tests which are supposed to be measures of school performance not individual attainment are re-used as risk indicators in Local Authority datasets used to identify families for intervention, which it’s not designed for.

- Vast amount of data distribution and linkage with other data: policing, economic drivers (LEO) and Local Authority broad data linkage without consent for purposes that exceed the original data collection purpose parents are told and use it like Kent, or Camden, “for profiling the needs of the 38,000 families across the borough” plus further automated decision-making.

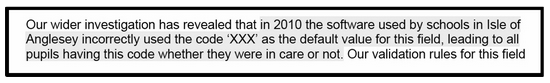

- Accuracy in education data is a big issue, in part because families never get to see the majority of data created about a child much of which is opinion, and not submitted by them: ie the Welsh government fulfilled a Subject Access Request to one parent concerned with their own child’s record, and ended up revealing that every child in 2010 had been wrongly recorded thanks to a Capita SIMS coding error, as having been in-care at some point in the past. Procurement processes should build penalties for systemic mistakes and lessons learned like this, into service level agreements, but instead we seem to allow the same issues to repeat over and over again.

What the DfE Does today

Government needs to embrace the fact it can only get data right, if it does the right thing. That includes policy that upholds the law by design. This needs change in its own purposes and practice.

National Pupil Data is a bad example from the top down. The ICO 2019-20 audit of the Department for Education — it is not yet published in full but findings included failings such as no Record of Processing Activity (ROPA), Not able to demonstrate compliance, and no fair processing. All of which will be undermined further by the Bill.

The Department for Education has been giving away 15 million people’s personal confidential data since 2012 and never told them. They know this. They choose to ignore it. And on top of that, didn’t inform people who were in school since then, that Mr Gove changed the law. So now over 21 million people’s pupil records are being given away to companies and other third parties, for use in ways we do not expect, and it is misused too. In 2015, more secret data sharing began, with the Home Office. And another pilot in 2018 with the DWP.

Government wanted to and changed the law on education admin data in 2012 and got it wrong. Education data alone is a sin bin of bad habits and complete lack of public and professional engagement, before even starting to address data quality and accuracy and backwards looking policy built on bad historic data.

“The Commercial department do not have appropriate controls in place to protect personal data being processed on behalf of the DfE by data processors.” (ICO audit of the DfE , 2020)

Gambling companies ended up misusing access to learner records for over two years exposed in 2020 by journalists at the Sunday Times.

The government wanted nationality data from the Department for Education to be collected for the purposes of another (the Home Office) and got it very wrong. People boycotted the collection until it was killed off and data later destroyed.

Government changed the law on Higher Education in 2017 and got it wrong. Now third parties pass around named equality monitoring records like religion, sexual orientation, and disability and it is stored forever on named national pupil records. The Department for Education (DfE) now holds sexual orientation data on almost 3.2 million, and religious belief data on 3.7 million people.

After the summary findings published by the ICO of their compulsory audit of the Department for Education, the question now is what will the Department and government do to address the 139 recommendations for improvement, with over 60% classified as urgent or high priority. Is the government intentional about change? We don’t think so at defend digital me, so we are, and welcome any support of our legal challenge.

Before we write new national law we must recognise and consider UK inconsistency and differences across education

Existing frameworks law and statutory guidance and recommendations need understood in the round (eg devolved education, including the age of a child and their capacity to undertake a contract in Scotland (at 16), the geographical applications of the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012, also the Prevent Duty since 2015 and its wider effects as a result of profiling children in counter-terrorism that reach beyond poor data protection and impacts on privacy (see The UN Special Rapporteur 2014 report on children’s rights and freedom of expression) – a plethora of Council of Europe work is applicable here in education that applies to UK as a member state: guidelines on data protection, AI, human rights, rule of law and the role of education in the promotion of democratic citizenship and a protection against authoritarian regimes and extreme nationalism.

The Bill itself

The fundamental principles of the GDPR and Data Protection law are undermined further from an already weak starting point since the 2018 Bill adopted exemptions that were not introduced by other countries in immigration and law enforcement.

- The very definitions of personal and biometric data need close scrutiny.

- Accountability is weakened (DPO, DPIA and prior consultation for high risk no longer necessary, ROPA)

- Purpose limitation is weakened (legitimate interests and additional conditions for LI)

- Redress is missing (Children and routes for child justice)

- Henry VIII powers on customer data and business data must go.

- And of course it only covers the living. What about children’s data misuse that causes distress and harms to human dignity but that is not covered strictly by UK Data Protection law, such as the children whose identities were used for undercover police in the SpyCops scandal. Recital 27 under the GDPR permits a possible change here.

Where are the Lessons Learned reflected in the Bill?

This Bill should be able to look at recent ICO enforcement action or judicial reviews to learn where and what is working and not working in data protection law. Lessons learned should be plentiful on public communications and fair processing, on the definitions of research, on discrimination, accuracy and bad data policy decisions. But where are those lessons in the Bill learned from health data sharing, why the care.data programme ran into trouble and similar failures repeated in the most recent GP patient data grab, or Google DeepMind and the RoyalFree? In policing from the Met Police Gangs Matrix? In Home Affairs from the judicial review launched to challenge the lawfulness of an algorithm used by the Home Office to process visa applications? Or in education from the summer of 2020 exams fiasco?

The major data challenges as a result of government policy are not about data at all, but bad policy decisions which invariably mean data is involved because of ubiquitous digital first policy, public administration, and the nature of digital record keeping. In education examples include:

- Partisan political agendas: i.e. the narrative of absence numbers makes no attempt to disaggregate the “expected” absence rate from anything on top, and presenting the idea as fact, that 100,000 children have not returned to school, “as a result of all of this”, is badly misleading to the point of being a lie.

- Policy that ignores the law. The biggest driver of profiling children in the state education sector, despite the law that profiling children should not be routine, is the Progress 8 measure: about which Leckie & late Harvey Goldstein (2017) concluded in their work on the evolution of school league tables in England 1992-2016: ‘Contextual value-added’, ‘expected progress’ and ‘progress 8’ that, “all these progress measures and school league tables more generally should be viewed with far more scepticism and interpreted far more cautiously than have often been to date.”

The Direction of Travel

Can any new consultation or debate on the changes promised in data protection reform, ensure people have a say in future data governance, the topic for today, and what if any difference would it make?

Children’s voice and framing of children in National Data Strategy is woeful, either projected as victims or potential criminals. That must change.

Data protection law has existed in much similar form to today since 1984. Yet we have scant attention paid to it in ways that meet public expectations, fulfil parental and children’s expectations, or respect the basic principles of the law today. We have enabled technologies to enter into classrooms without any grasp of scale or risks in England that even Scotland has not with their Local Authority oversight and controls over procurement standards. Emerging technologies: tools that claim to be able to identify emotion and mood and use brain scanning, the adoption of e-proctoring, and mental health prediction apps which are treated very differently from they would be in the NHS Digital environment with ethical oversight and quality standards to meet — these are all in classrooms interfering with real children’s lives and development now, not some far-off imagined future.

This goes beyond data protection into procurement, standards, safety, understanding pedagogy, behavioural influence, and policy design and digital strategy. It is furthermore, naive to think this legislation, if it happens at all, is going to be the piece of law that promotes children’s rights when the others in play from the current government do not: the revision of the Human Rights Act, the recent PCSC Bill clauses on data sharing, and the widespread use of exemptions and excuses around data for immigration enforcement.

Conclusion

If policymakers who want more data usage treat people as producers of a commodity, and continue to ignore the publics’ “say in future data governance” then we’ll keep seeing the boycotts and the opt-outs and create mistrust in government as well as data conveners and controllers widening the data trust deficit**. The culture must change in education and other departments.

Overall, we must reconcile the focus of the UK national data strategy, with a rights-based governance framework to move forward the conversation in ways that work for the economy and research, and with the human flourishing of our future generations at its heart. Education data plays a critical role in social, economic, democratic and even security policy today and should be recognised as needing urgent and critical attention.

References:

- RAENG (2010) On children and health data Privacy and Prejudice: young people’s views on the development and use of Electronic Patient Records (911.18 KB). They are very clear about wanting to keep their medical details under their own control and away from the ‘wrong hands’ which includes potential employers, commercial companies and parents.

- ADRN (2013) on *deidentified* personal data including “Dialogues on Data” report on creating mega databases and commercial re-use

- **The Royal Statistical Society (RSS) (2014) https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/new-research-finds-data-trust-deficit-lessons-policymakers The data trust deficit with lessons for policymakers

- UCAS applicant survey with 37,000 respondents (2015) https://www.ucas.com/corporate/news-and-key-documents/news/37000-students-respond-ucas%E2%80%99-applicant-data-survey A majority of UCAS applicants (64%) agree that sharing personal data can benefit them and support research into university admissions, but they want to stay firmly in control, with nine out of ten saying they should be asked first.

- Wellcome Trust/ Ipsos MORI (2017) The One-Way Mirror: Public attitudes to commercial access to health data https://wellcome.figshare.com/articles/journal%20contribution/The_One-Way_Mirror_Public_attitudes_to_commercial_access_to_health_data/5616448/1

- defenddigitalme (2018) Parents’ poll ‘Only half of parents think they have enough control of children’s digital footprint’. defenddigitalme.org/2018/03/only-h

- DotEveryone(2018-20) doteveryone.org.uk/project/people Their public attitudes report found that although people’s digital understanding has grown, that’s not helping them to shape their online experiences in line with their own wishes.

- LSE (2019-20) Children’s privacy online lse.ac.uk/my-privacy-uk

Local Authority algorithms

The Data Justice Lab has researched how public services are increasingly automated and government institutions at different levels are using data systems and AI. However, our latest report, Automating Public Services: Learning from Cancelled Systems, looks at another current development: The cancellation of automated decision-making systems (ADS) that did not fulfil their goals, led to serious harm, or met caused significant opposition through community mobilization, investigative reporting, or legal action. The report provides the first comprehensive overview of systems being cancelled across western democracies.