Parliament’s talking about Talk Talk and Big Data, like some parents talk about sex ed. They should be discussing prevention and personal data protection for all our personal data, not just one company, after the event.

Everyone’s been talking about TalkTalk and for all the wrong reasons. Data loss and a 15-year-old combined with a reportedly reckless response to data protection, compounded by lack of care.

As Rory Cellan-Jones wrote [1] rebuilding its reputation with customers and security analysts is going to be a lengthy job.

In Parliament Chi Onwarah, Shadow Minister for Culture & the Digital Economy, summed up in her question, asking the Minister to acknowledge “that all the innovation has come from the criminals while the Government sit on their hands, leaving it to businesses and consumers to suffer the consequences?” [Hansard 2]

MPs were concerned for the 4 million* customers’ loss of name, date of birth, email, and other sensitive data, and called for an inquiry. [It may now be fewer*.] [3] The SciTech committee got involved too.

I hope this means Parliament will talk about TalkTalk not as the problem to be solved, but as one case study in a review of contemporary policy and practices in personal data handling.

Government spends money in data protection work in the [4] “National Cyber Security Programme”. [NCSP] What is the measurable outcome – particularly for TalkTalk customers and public confidence – from its £860M budget? If you look at the breakdown of those sums, with little going towards data protection and security compared with the Home Office and Defence, we should ask if government is spending our money in an appropriately balanced way on the different threats it perceives. Keith Vaz suggested British companies that lose £34 billion every year to cybercrime. Perhaps this question will come into the inquiry.

This all comes after things have gone wrong. Again [5]. An organisation we trusted has abused that trust by not looking after data with the stringency that customers should be able to expect in the 21st century, and reportedly not making preventative changes, apparent a year ago. Will there be consequences this time?

The government now saying it is talking about data protection and consequences, is like saying they’re talking sex education with teens, but only giving out condoms to the boys.

It could be too little too late. And they want above all to avoid talking about their own practices. Let’s change that.

Will this mean a review to end risky behaviour, bring in change, and be wiser in future?

If MPs explore what the NCSP does, then we the public, should learn more about what government’s expectations of commercial companies is in regards modern practices.

In addition, any MPs’ inquiry should address government’s own role in its own handling of the public’s personal data. Will members of government act in a responsible manner or simply tell others how to do so?

Public discussion around both commercial and state use of our personal data, should mean genuine public engagement. It should involve a discussion of consent where necessary for purposes beyond those we expect or have explained when we submit our data, and there needs to be a change in risky behaviour in terms of physical storage and release practices, or all the talk, is wasted.

Some say TalkTalk’s practices mean they have broken their contract along with consumer trust. Government departments should also be asking whether their data handling would constitute a breach of the public’s trust and reasonable expectations.

Mr Vaizey should apply his same logic to government handling data as he does to commercial handling. He said he is open to suggestions for improvement. [6]

Let’s not just talk about TalkTalk.

- Let’s Talk Consequences: organisations taking risk seriously and meaningful consequences if not [7]

- Let’s Talk Education: the education of the public on personal data use by others and rights and responsibilities we have [8]

- Let’s Talk Parliament’s Policies and Practices: about its own complementary lack of data understanding in government and understand what good practice is in physical storage, good governance and transparent oversight

- Let’s Talk Public Trust: and the question whether government can be trusted with public data it already has and whether its current handling makes it trustworthy to take more [9]

Vaizey said of the ICO now in his own department: “The Government take the UK’s cyber-security extremely seriously and we will continue to do everything in our power to protect organisations and individuals from attacks.”

“I will certainly meet the Information Commissioner to look at what further changes may be needed in the light of this data breach. [..] It has extensive powers to take action and, indeed, to levy significant fines. “

So what about consequences when data are used in ways the public would consider a loss, and not through an attack or a breach, but government policy? [10]

Let’s Talk Parliament’s Policies and Practices

Commercial companies are not alone in screwing up the use and processing [11] management of our personal data. The civil service under current policy seems perfectly capable of doing by itself. [12]

Government data policy has not kept up with 21st century practices and to me seems to work in the dark, as Chi Onwarah said,

‘illuminated by occasional flashes of incompetence.’

This incompetence can risk harm to people’s lives, to business and to public confidence.

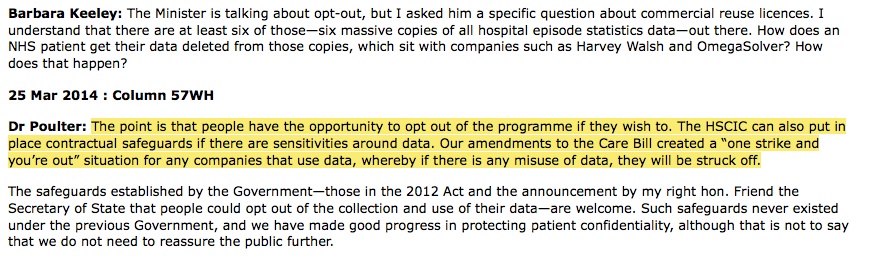

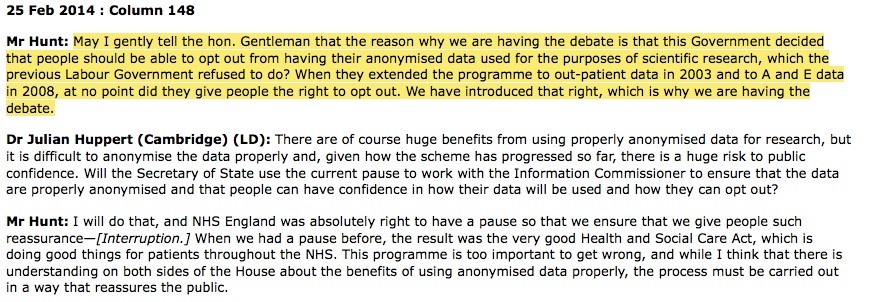

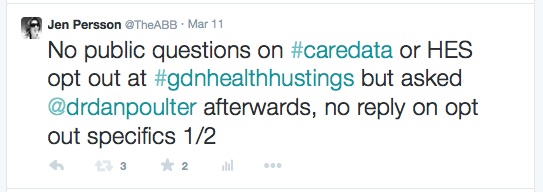

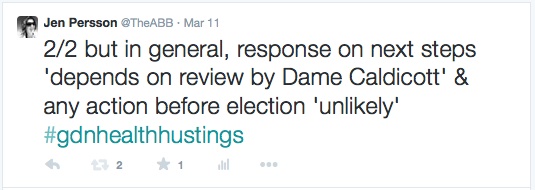

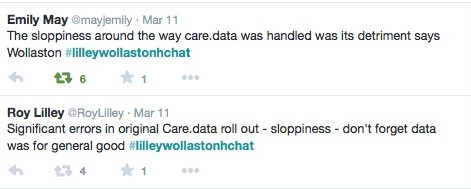

And once given, trust would be undermined by changing the purposes or scope of use for which it was given, for example as care.data plans to do after the pilot. A most risky idea.

Trust in these systems, whether commercial or state, is crucial. Yet reviews which highlight this, and make suggestions to support trust such as ‘data should never be (and currently is never) released with personal identifiers‘ in The Shakespeare Review have been ignored by government.

Where our personal data are not used well in government departments by the department themselves, they seem content to date to rely on public ignorance to get away with current shoddy practices.

Practices such as not knowing who all your customers are, because they pass data on to others. Practices, such as giving individual level identifiable personal data to third parties without informing the public, or asking for consent. Practices, such as never auditing or measuring any benefit of giving away others personal data.

“It is very important that all businesses, particularly those handling significant amounts of sensitive customer data, have robust procedures in place to protect those data and to inform customers when there may have been a data breach.” Ed Vaizey, Oct 26th, HOC

If government departments prove to be unfit to handle the personal data we submit in trust to the state today, would we be right to trust them with even more?

While the government is busy wagging fingers at commercial data use poor practices, the care.data debacle is evidence that not all its MPs or civil service understand how data are used in commercial business or through government departments.

MPs calling for commercial companies to sharpen up their data protection must understand how commercial use of data often piggy-backs the public use of our personal data, or others getting access to it via government for purposes that were unintended.

Let’s Talk Education

If the public is to understand how personal data are to be kept securely with commercial organisations, why should they not equally ask to understand how the state secures their personal data? Educating the public could lead to better engagement with research, better understanding of how we can use digital services and a better educated society as a whole. It seems common sense.

At a recent public event [13], I asked civil servants talking about big upcoming data plans they announced, linking school data with more further education and employment data, I asked how they planned to involve the people whose data they would use. There was no public engagement to mention. Why not? Inexcusable in this climate.

Public engagement is a matter of trust and developing understanding in a relationship. Organisations must get this right.[14]

If government is discussing risky practices by commercial companies, they also need to look closer to home and fix what is broken in government data handling where it exposes us to risk through loss of control of our personal data.

The National Pupil Database for example, stores and onwardly shares identifiable individual sensitive data of at least 8m children’s records from age 2 -19. That’s twice as big as the TalkTalk loss was first thought to be.

Prevention not protection is what we should champion. Rather than protection after the events, MPs and public must demand emphasis on prevention measures in our personal data use.

This week sees more debate on how and why the government will legislate to have more powers to capture more data about all the people in the country. But are government policy, process and practices fit to handle our personal data, what they do with it and who they give it to?

Population-wide gathering of data surveillance in any of its many forms is not any less real just because you don’t see it. Children’s health, schools, increases in volume of tax data collection. We don’t discuss enough how these policies can be used every day without the right oversight. MPs are like the conservative parents not comfortable talking to their teens about sleeping with someone. Just because you don’t know, it doesn’t mean they’re not doing it. [15] It just means you don’t want to know because if you find out they’re not doing it safely, you’ll have to do something about it.

And it might be awkward. (Meanwhile in schools real, meaningful PHSE has been left off the curriculum.)

Mr. Vaizey asked in the Commons for suggestions for improvement.

My suggestion is this. How government manages data has many options. But the principle should be simple. Our personal data needs not only protected, but not exposed to unnecessary risk in the first place, by commercial or state bodies. Doing nothing, is not an option.

Let’s Talk about more than TalkTalk

Teens will be teens. If commercial companies can’t manage their systems better to prevent a child successfully hacking it, then it’s not enough to point at criminal behaviour. There is fault to learn from on all sides. In commercial and state uses of personal data.

There is talk of new, and bigger, data sharing plans. [16]

Will the government wait to see and keep its fingers crossed each month to see if our data are used safely at unsecured settings with some of these unknown partners data might be onwardly shared with, hoping we won’t find out and they won’t need to talk about it, or have a grown up public debate based on public education?

Will it put preventative measures in place appropriate to the sensitivity and volume of the data it is itself responsible for?

Will moving forward with new plans mean safer practices?

If government genuinely wants our administrative data at the heart of digital government fit for the 21st century, it must first understand how all government departments collect and use public data. And it must educate the public in this and commercial data use.

We need a fundamental shift in the way the government respects public opinion and shift towards legal and privacy compliance – both of which are lacking.

Let’s not talk about TalkTalk. Let’s have meaningful grown up debate with genuine engagement. Let’s talk about prevention measures in our data protection. Let’s talk about consent. It’s personal.

******

[1] Questions for TalkTalk: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-34636308

[2] Hansard: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmhansrd/cm151026/debtext/151026-0001.htm#15102612000004

[3] TalkTalk update: http://www.talktalkgroup.com/press/press-releases/2015/cyber-attack-update-tuesday-october-30-2015.aspx

[4] The Cyber Security Programme: http://www.civilserviceworld.com/articles/feature/depth-look-national-cyber-security-programme

[5] Paul reviews TalkTalk; https://paul.reviews/value-security-avoid-talktalk/

[6] https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-data-protection/conditions-for-processing/

[7] Let’s talk Consequences: the consequences of current failures to meet customers’ reasonable expectations of acceptable risk, are low compared with elsewhere. As John Nicolson (East Dunbartonshire) SNP pointed out in the debate, “In the United States, AT&T was fined £17 million for failing to protect customer data. In the United Kingdom, the ICO can only place fines of up to £500,000. For a company that received an annual revenue of nearly £1.8 billion, a fine that small will clearly not be terrifying. The regulation of telecoms must be strengthened to protect consumers.”

[8] Let’s talk education: FOI request revealing a samples of some individual level data released to members of the press: http://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2015-10-26b.32.0

The CMA brought out a report in June, on the use of consumer data, the topic should be familiar in parliament, but little engagement has come about as a result. It suggested the benefit:

“will only be realised if consumers continue to provide data and this relies on them being able to trust the firms that collect and use it”, and that “consumers should know when and how their data is being collected and used and be able to decide whether and how to participate. They should have access to information from firms about how they are collecting, storing and using data.”

[9] Let’s Talk Public Trust – are the bodies involved Trustworthy? Government lacks an effective data policy and is resistant to change. Yet it wants to collect ever more personal and individual level for unknown purposes from the majority of 60m people, with an unprecedented PR campaign. When I heard the words ‘we want a mature debate’ it was reminiscent of HSCIC’s ‘intelligent grown up debate’ requested by Kinglsey Manning, in a speech when he admitted lack of public knowledge was akin to a measure of past success, and effectively they would rather have kept the use of population wide health data ‘below the radar’.

Change: We need change, the old way after all, didn’t work, according to Minister Matt Hancock: “The old model of government has failed, so we will build a new one.” I’d like to see what that new one will look like. Does he mean to expand only data sharing policy, or the powers of the civil service?

[10] National Pupil Database detailed data releases to third parties https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/pupil_data_national_pupil_databa

[11] http://adrn.ac.uk/news-events/latest-news/adrn-rssevent

[12] https://jenpersson.com/public-trust-datasharing-nib-caredata-change/

[13] https://www.liberty-human-rights.org.uk/human-rights/privacy/state-surveillance