A reflection for World Children’s Day 2021. In ten years’ time my three children will be in their twenties. What will they and the world around them have become? What will shape them in the years in between?

Today when people talk about AI, we hear fears of consciousness in AI. We see, I, Robot. The reality of any AI that will touch their lives in the next ten years is very different. The definition may be contested but artificial intelligence in schools already involves automated decision making at speed and scale, without compassion or conscience, but with outcomes that affect children’s lives for a long time.

The guidance of today—in policy documents, and well intentioned toolkits and guidelines and oh yes yet another ‘ethics’ framework— is all fairly same-y in terms of the issues identified.

Bias in training data. Discrimination in outcomes. Inequitable access or treatment. Lack of understandability or transparency of decision-making. Lack of routes for redress. More rarely thoughts on exclusion, disability and accessible design, and the digital divide. In seeking to fill it, the call can conclude with a cry to ensure ‘AI for all’.

Most of these issues fail to address the key questions in my mind, with regards to AI in education.

Who gets to shape a child’s life and the environment they grow up in? The special case of children is often used for special pleading in government tech issues. Despite this, in policy discussion and documents, govt. fails over and over again to address children as human beings.

Children are still developing. Physically, emotionally, their sense of fairness and justice, of humor, of politics and who they are.

AI is shaping children in ways that schools and parents cannot see. And the issues go beyond limited agency and autonomy. Beyond the UNCRC articles 8 and 18, the role of the parent and lost boundaries between schools and home, and 23 and 29. (See at the end in detail).

Concerns about accessibility published on AI are often about the individual and inclusion, in terms of design to be able to participate. But once they can participate, where is the independent measurement and evaluation of impact on their educational progress, or physical and mental development? What is their effect?

From overhyped like Edgenuity, to the oversold like ClassCharts (that didn’t actually have any AI in it but it still won Bett Show Awards), frameworks often mention but still have no meaningful solutions for the products that don’t work and fail.

But what about the harms from products that work as intended? These can fail human dignity or create a chilling effect, like exam proctoring tech. Those safety tech that infer things and cause staff to intervene even if the child was only chatting about ‘a terraced house.’ Punitive systems that keep profiles of behaviour points long after a teacher would have let it go. What about those shaping the developing child’s emotions and state of mind by design and claim to operate within data protection law? Those who measure and track mental health or make predictions for interventions by school staff?

Brain headbands to transfer neurosignals aren’t biometric data in data protection terms if not used to or able to uniquely identify a child.

“Wellbeing” apps are not being regulated as medical devices and yet are designed to profile and influence mental health and mood and schools adopt them at scale.

If AI is being used to deliver a child’s education, but only in the English language, what risk does this tech-colonialism create in evangelising children in non-native English speaking families through AI, not only in access to teaching, but on reshaping culture and identity?

At the institutional level, concerns are only addressed after the fact. But how should they be assessed as part of procurement when many AI are marketed as , it never stops “learning about your child”? Tech needs full life-cycle oversight, but what companies claim their products do is often only assessed to pass accreditation at a single point in time.

But the biggest gap in governance is not going to be fixed by audits or accreditation of algorithmic fairness. It is the failure to recognize the redistribution of not only agency but authority; from individuals to companies (teacher doesn’t decide what you do next, the computer does). From public interest institutions to companies (company X determines the curriculum content, not the school). And from State to companies (accountability for outcomes has fallen through the gap in outsourcing activity to the AI company). We are automating authority, and with it the shirking of responsibility, the liability for the machine’s flaws, and accepting it is the only way, thanks to our automation bias. Accountability must be human, but whose?

Around the world the rush to regulate AI, or related tech in Online Harms, or Digital Services, or Biometrics law, is going to embed, not redistribute power, through regulatory capitalism.

We have regulatory capture including on government boards and bodies that shape the agenda; unrealistic expectations of competition shaping the market; and we’re ignoring transnational colonialisation of whole schools or even regions and countries shaping the delivery of education at scale.

We’re not regulating the questions: Who does the AI serve and how do we deal with conflicts of interest between child’s rights, family, school staff, the institution or State, and the company’s wants? Where do we draw the line between public interest, private interests, and who decides what are the best interests of each child?

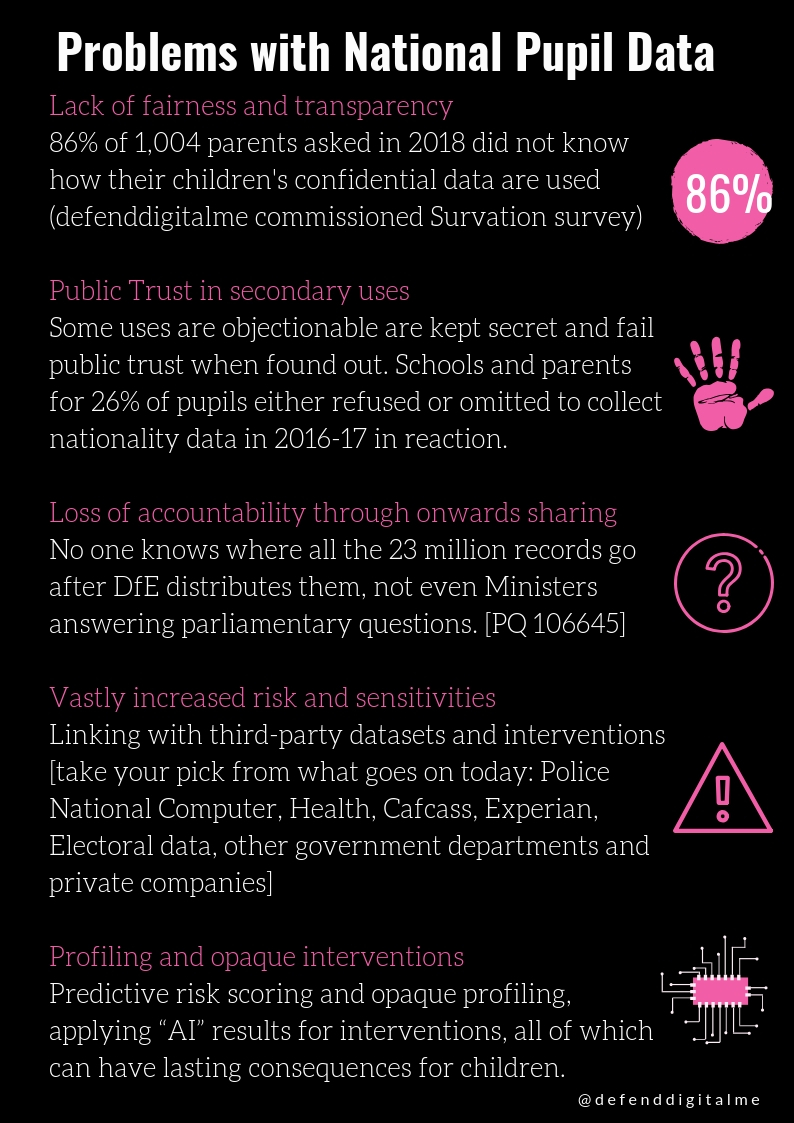

We’re not managing what the implications are of the datafied child being mined and analysed in order to train companies’ AI. Is it ethical or desirable to use children’s behaviour as sources of business intelligence, to donate free labour in school systems performed for companies to profit from, without any choice (see UNCRC Art 32)?

We’re barely aware as parents, if a company will decide how a child is tested in a certain way, asked certain questions about their mental health, given nudges to ‘improve’ their performance or mood. It’s not a question of ‘is it in the best interests of a child’, but rather, who designs it and can schools assess compatibility with a child’s fundamental rights and freedoms to develop free from interference?

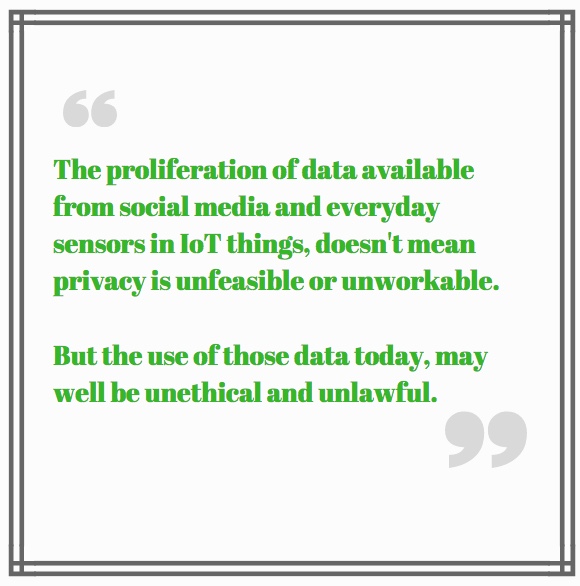

It’s not about protection of ‘the data’ although data protection should be about the protection of the person, not only enabling data flows for business.

It’s about protection from strangers engineering a child’s development in closed systems.

It is about child protection from unknown and unlimited number of persons interfering with who they will become.

Today’s laws and debate are too often about regulating someone else’s opinion; how it should be done, not if it should be done at all.

It is rare we read any challenge of the ‘inevitability’ of AI [in education] narrative.

Who do I ask my top two questions on AI in education:

(a) who gets and grants permission to shape my developing child, and

(b) what happens to the duty of care in loco parentis as schools outsource authority to an algorithm?

UNCRC

Article 8

1. States Parties undertake to respect the right of the child to preserve his or her identity, including nationality, name and family relations as recognised by law without unlawful interference.

Article 18

1. States Parties shall use their best efforts to ensure recognition of the principle that both parents have common responsibilities for the upbringing and development of the child. Parents or, as the case may be, legal guardians, have the primary responsibility for the upbringing and development of the child. The best interests of the child will be their basic concern.

Article 29

1. States Parties agree that the education of the child shall be directed to:

(a) The development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential;

(c) The development of respect for the child’s parents, his or her own cultural identity, language and values, for the national values of the country in which the child is living, the country from which he or she may originate, and for civilizations different from his or her own;

Article 30

In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities or persons of indigenous origin exist, a child belonging to such a minority or who is indigenous shall not be denied the right, in community with other members of his or her group, to enjoy his or her own culture