Call the midwife [if you can find one free, the underpaid overworked miracle workers that they are], the care.data ‘pathfinder’ pilots are on their way! [This is under a five minute read, so there should be time to get the hot water on – and make a cup of tea.]

I’d like to be able to say I’m looking forward to a happy new arrival, but I worry care.data is set for a breech birth. Is there still time to have it turned around? I’d like to say yes, but it might need help.

The pause appears to be over as the NHS England board delegated the final approval of directions to their Chair, Sir Malcolm Grant and Chief Executive, Simon Stevens, on Thursday May 28.

Directions from NHS England which will enable the HSCIC to proceed with their pathfinder pilots’ next stage of delivery.

“this is a programme in which we have invested a great deal, of time and thought in its development.” [Sir Malcolm Grant, May 28, 2015, NHS England Board meeting]

And yet. After years of work and planning, and a 16 month pause, as long as it takes for the gestation of a walrus, it appears the directions had flaws. Technical fixes are also needed before the plan could proceed to extract GP care.data and merge it with our hospital data at HSCIC.

And there’s lots of unknowns what this will deliver.**

Groundhog Day?

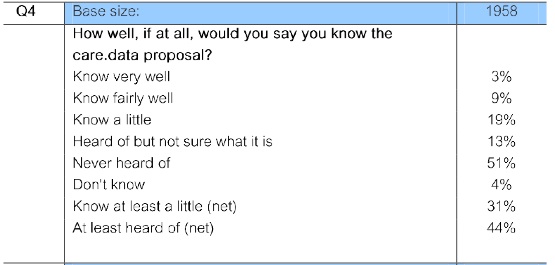

The public and MPs were surprised in 2014. They may be even more surprised if 2015 sees a repeat of the same again.

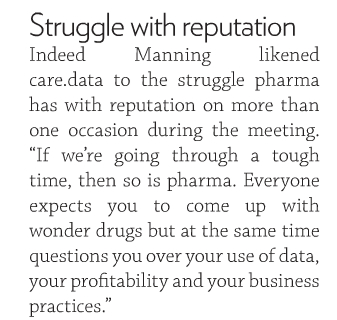

We have yet to hear case studies of who received data in the past and would now be no longer eligible. Commercial data intermediaries? Can still get data, the NHS Open Day was told. And they do, as the HSCIC DARS meeting minutes in 2015 confirm.

By the time the pilots launch, the objection must actually work, communications must include an opt out form and must clearly give the programme a name.

I hope that those lessons have been learned, but I fear they have not been. There is still lack of transparency. NHS England’s communications materials and May-Oct 2014 and any 2015 programme board minutes have not been published.

We have been here before.

Back to September 2013: the GPES Advisory Committee, the ICO and Dame Fiona Caldicott, as well as campaigners and individuals could see the issues in the patient leaflet and asked for fixes.The programme went ahead anyway in February 2014 and although foreseen, failed to deliver. [For some, quite literally.]

These voices aren’t critical for fun, they call for fixes to get it right.

I would suggest that all of the issues raised since April 2014, were broadly known in February 2014 before the pause began. From the public listening exercise, the high level summary captures some issues raised by patients, but doesn’t address their range or depth.

Some of the difficult and unwanted issues, are still there, still the same and still being ignored, at least in the public domain. [4]

A Healthy New Arrival?

How is the approach better now and what happens next to proceed?

“It seems a shame,” the Walrus said, “To play them such a trick, After we’ve brought them out so far, And made them trot so quick!” [Lewis Carroll]

When asked by a board member: What is it we seek to learn from the pathfinder approach that will guide us in the decision later if this will become a national approach? it wasn’t very clear. [full detail end of post]

First they must pass the tests asked of them by Dame Fiona [her criteria and 27 questions from before Christmas.] At least that was what the verbal background given at the board meeting explained.

If the pilots should be a dip in the water of how national rollouts will proceed, then they need to test not just for today, but at least for the known future of changing content scope and expanding users – who will pay for the communication materials’ costs each time?

If policy keeps pressing forward, will it not make these complications worse under pressure? There may be external pressure ahead as potential changes to EU data protection are expected this year as well, for which the pilot must be prepared and design in advance for the expectations of best practice.

Pushing out the pathfinder directions, before knowing the answers to these practical things and patient questions open for over 16 months, is surely backwards. A breech birth, with predictable complications.

If in Sir Malcolm Grant’s words:

“we would only do this if we believed it was absolutely critical in the interests of patients.” [Malcom Grant, May 28, 2015, NHS England Board meeting]

then I’d like to see the critical interest of patients put first. Address the full range of patient questions from the ‘listening pause’.

In the rush to just fix the best of a bad job, we’ve not even asked are we even doing the right thing? Is the system designed to best support doctor patient needs especially with the integration “blurring the lines” that Simon Stevens seems set on.

If focus is on the success of the programme and not the patient, consider this: there’s a real risk too many opt out due to these unknowns. And lack of real choice on how their data gets used. It could be done better to reduce that risk.

What’s the percentage of opt out that the programme deems a success to make it worthwhile?

In March 2014, at a London event, a GP told me all her patients who were opting out were the newspaper reading informed, white, middle class. She was worried that the data that would be included, would be misleading and unrepresentative of her practice in CCG decision making.

medConfidential has written a current status for pathfinder areas that make great sense to focus first on fixing care.data’s big post-election question the opt out that hasn’t been put into effect. Of course in February 2014 we had to choose between two opt outs -so how will that work for pathfinders?

In the public interest we need collectively to see this done well. Another mis-delivery will be fatal. “No artificial timelines?”

Right now, my expectations are that the result won’t be as cute as a baby walrus.

******

Notes from the NHS England Board Meeting, May 28, 2015:

TK said: “These directions [1] relate only to the pathfinder programme and specify for the HSCIC what data we want to be extracted in the event that Dame Fiona, this board and the Secretary of State have given their approval for the extraction to proceed.

“We will be testing in this process a public opt out, a citizen’s right to opt out, which means that, and to be absolutely clear if someone does exercise their right to opt out, no clinical data will be extracted from their general practice, just to make that point absolutely clearly.

“We have limited access to the data, should it be extracted at the end of the pathfinder phase, in the pathfinder context to just four organisations: NHS England, Public Health England, the HSCIC and CQC.”

“Those four organisations will only be able to access it for analytic purposes in a safe, a secure environment developed by the Information Centre [HSCIC], so there will be no third party hosting of the data that flows from the extraction.

“In the event that Dame Fiona, this board, the Secretary of State, the board of the Information Centre, are persuaded that there is merit in the data analysis that proceeds from the extraction, and that we’ve achieved an appropriate standard of what’s called fair processing, essentially have explained to people their rights, it may well be that we proceed to a programme of national rollout, in that case this board will have to agree a separate set of directions.”

“This is not signing off anything other than a process to test communications, and for a conditional approval on extracting data subject to the conditions I’ve just described.”

CD said: “This is new territory, precedent, this is something we have to get right, not only for the pathfinders but generically as well.”

“One of the consequences of having a pathfinder approach, is as Tim was describing, is that directions will change in the future. So if we are going to have a truly fair process , one of the things we have to get right, is that for the pathfinders, people understand that the set of data that is extracted and who can use it in the pathfinders, will both be a subset of, the data that is extracted and who can use it in the future. If we are going to be true to this fair process, we have to make sure in the pathfinders that we do that.

“For example, at the advisory group last week, is that in the communication going forward we have to make sure that we flag the fact there will be further directions, and they will be changed, that we are overt in saying, subject to what Fiona Caldicott decides, that process itself will be transparent.”

Questions from Board members:

Q: What is it we seek to learn from the pathfinder approach that will guide us in the decision later if this will become a national approach?

What are the top three objectives we seek to achieve?

TK: So, Dame Fiona has set a series of standards she expects the pathfinders to demonstrate, in supporting GPs to be able to discharge this rather complex communication responsibility, that they have under the law in any case.

“On another level how we can demonstrate that people have adequately understood their right to opt out [..]

“and how do we make sure that populations who are relatively hard to reach, although listed with GPs, are also made aware of their opportunity to opt out.

Perhaps it may help if I forward this to the board, It is in the public domain. But I will forward the letter to the board.”

“So that lays out quite a number of specific tangible objectives that we then have to evaluate in light of the pathfinder experience. “

Chair: “this is a programme in which we have invested a great deal, of time and thought in its development, we would only do this if we believed it was absolutely critical in the interests of patients, it was something that would give us the information the intelligence that we need to more finely attune our commissioning practice, but also to get real time intelligence about how patients lives are lived, how treatments work and how we can better provide for their care.

“I don’t think this is any longer a matter of huge controversy, but how do we sensitively attune ourselves to patient confidentiality.”

“I propose that […] you will approve in principle the directions before you and also delegate to the Chief Executive and to myself to do final approval on behalf of the board, once we have taken into account the comments from medConfidential and any other issues, but the substance will remain unchanged.”

******

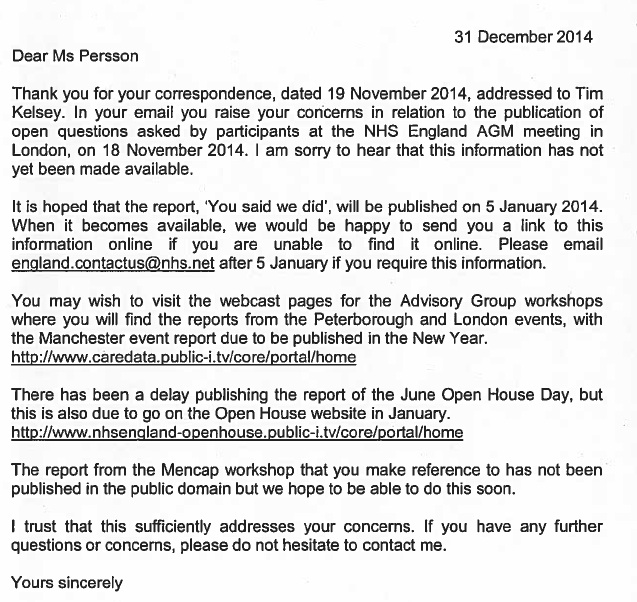

[4] request for the release of June 2014 Open House feedback still to be published in the hope that the range and depth of public questions can be addressed.

******

“The time has come,” the walrus said, “to talk of many things.”

[From ‘The Walrus* and the Carpenter’ in Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll]

*A walrus has a gestation period of about 16 months.

The same amount of time which the pause in the care.data programme has taken to give birth to the pathfinder sites.

references:

[1] NHS England Directions to HSCIC: May 28 2015 – http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/item6-board-280515.pdf

[2] Notes from care.data advisory group meeting on 27th February 2015

[3] Patient questions: https://jenpersson.com/pathfinder/

[4] Letter from NHS England in response to request from September, and November 2014 to request that public questions be released and addressed

15 Jan 2024: Image section in header replaced at the request of likely image tracing scammers who don’t own the rights and since it and this blog is non-commercial would fall under fair use anyway. However not worth the hassle. All other artwork on this site is mine.