Lords have voiced criticism and concern at plans for ‘free market’ universities, that will prioritise competition over collaboration and private interests over social good. But while both Houses have identified the institutional effects, they are yet to discuss the effects on the individuals of a bill in which “too much power is concentrated in the centre”.

The Higher Education and Research Bill sucks in personal data to the centre, as well as power. It creates an authoritarian panopticon of the people within the higher education and further education systems. Section 1, parts 72-74 creates risks but offers no safeguards.

Applicants and students’ personal data is being shifted into a top-down management model, at the same time as the horizontal safeguards for its distribution are to be scrapped.

Through deregulation and the building of a centralised framework, these bills will weaken the purposes for which personal data are collected, and weaken existing requirements on consent to which the data may be used at national level. Without amendments, every student who enters this system will find their personal data used at the discretion of any future Secretary of State for Education without safeguards or oversight, and forever. Goodbye privacy.

Part of the data extraction plans are for use in public interest research in safe settings with published purpose, governance, and benefit. These are well intentioned and this year’s intake of students will have had to accept that use as part of the service in the privacy policy.

But in addition and separately, the Bill will permit data to be used at the discretion of the Secretary of State, which waters down and removes nuances of consent for what data may or may not be used today when applicants sign up to UCAS.

Applicants today are told in the privacy policy they can consent separately to sharing their data with the Student Loans company for example. This Bill will remove that right when it permits all Applicant data to be used by the State.

This removal of today’s consent process denies all students their rights to decide who may use their personal data beyond the purposes for which they permit its sharing.

And it explicitly overrides the express wishes registered by the 28,000 applicants, 66% of respondents to a 2015 UCAS survey, who said as an example, that they should be asked before any data was provided to third parties for student loan applications (or even that their data should never be provided for this).

Not only can the future purposes be changed without limitation, by definition, when combined with other legislation, namely the Digital Economy Bill that is in the Lords at the same time right now, this shift will pass personal data together with DWP and in connection with HMRC data expressly to the Student Loans Company.

In just this one example, the Higher Education and Research Bill is being used as a man in the middle. But it will enable all data for broad purposes, and if those expand in future, we’ll never know.

This change, far from making more data available to public interest research, shifts the balance of power between state and citizen and undermines the very fabric of its source of knowledge; the creation and collection of personal data.

Further, a number of amendments have been proposed in the Lords to clause 9 (the transparency duty) which raise more detailed privacy issues for all prospective students, concerns UCAS share.

Why this lack of privacy by design is damaging

This shift takes away our control, and gives it to the State at the very time when ‘take back control’ is in vogue. These bills are building a foundation for a data Brexit.

If the public does not trust who will use it and why or are told that when they provide data they must waive any rights to its future control, they will withhold or fake data. 8% of applicants even said it would put them off applying through UCAS at all.

And without future limitation, what might be imposed is unknown.

This shortsightedness will ultimately cause damage to data integrity and the damage won’t come in education data from the Higher Education Bill alone. The Higher Education and Research Bill is just one of three bills sweeping through Parliament right now which build a cumulative anti-privacy storm together, in what is labelled overtly as data sharing legislation or is hidden in tucked away clauses.

The Technical and Further Education Bill – Part 3

In addition to entirely new Applicant datasets moving from UCAS to the DfE in clauses 73 and 74 of the Higher Education and Research Bill, Apprentice and FE student data already under the Secretary of State for Education will see potentially broader use under changed purposes of Part 3 of the Technical and Further Education Bill.

Unlike the Higher Education and Research Bill, it may not fundamentally changing how the State gathers information on further education, but it has the potential to do so on use.

The change is a generalisation of purposes. Currently, subsection 1 of section 54 refers to “purposes of the exercise of any of the functions of the Secretary of State under Part 4 of the Apprenticeships, Skills, Children and Learning Act 2009”.

Therefore, the government argues, “it would not hold good in circumstances where certain further education functions were transferred from the Secretary of State to some combined authorities in England, which is due to happen in 2018.”<

This is why clause 38 will amend that wording to “purposes connected with further education”.

Whatever the details of the reason, the purposes are broader.

Again, combined with the Digital Economy Bill’s open ended purposes, it means the Secretary of State could agree to pass these data on to every other government department, a range of public bodies, and some private organisations.

The TFE BIll is at Report stage in the House of Commons on January 9, 2017.

What could go possibly go wrong?

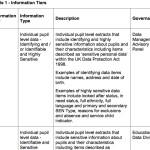

These loose purposes, without future restrictions, definitions of third parties it could be given to or why, or clear need to consult the public or parliament on future scope changes, is a repeat of similar legislative changes which have resulted in poor data practices using school pupil data in England age 2-19 since 2000.

Policy makers should consider whether the intent of these three bills is to give out identifiable, individual level, confidential data of young people under 18, for commercial use without their consent? Or to journalists and charities access? Should it mean unfettered access by government departments and agencies such as police and Home Office Removals Casework teams without any transparent register of access, any oversight, or accountability?

These are today’s uses by third-parties of school children’s individual, identifiable and sensitive data from the National Pupil Database.

Uses of data not as statistics, but named individuals for interventions in individual lives.

If the Home Secretaries past and present have put international students at the centre of plans to cut migration to the tens of thousands and government refuses to take student numbers out of migration figures, despite them being seen as irrelevant in the substance of the numbers debate, this should be deeply worrying.

Will the MOU between the DfE and the Home Office Removals Casework team be a model for access to all student data held at the Department for Education, even all areas of public administrative data?

Hoping that the data transfers to the Home Office won’t result in the deportation of thousands we would not predict today, may be naive.

Under the new open wording, the Secretary of State for Education might even decide to sell the nation’s entire Technical and Further Education student data to Trump University for the purposes of their ‘research’ to target marketing at UK students or institutions that may be potential US post-grad applicants. The Secretary of State will have the data simply because she “may require [it] for purposes connected with further education.”

And to think US buyers or others would not be interested is too late.

In 2015 Stanford University made a request of the National Pupil Database for both academic staff and students’ data. It was rejected. We know this only from the third party release register. Without any duty to publish requests, approved users or purposes of data release, where is the oversight for use of these other datasets?

If these are not the intended purposes of these three bills, if there should be any limitation on purposes of use and future scope change, then safeguards and oversight need built into the face of the bills to ensure data privacy is protected and avoid repeating the same again.

Hoping that the decision is always going to be, ‘they wouldn’t approve a request like that’ is not enough to protect millions of students privacy.

The three bills are a perfect privacy storm

As other Europeans seek to strengthen the fundamental rights of their citizens to take back control of their personal data under the GDPR coming into force in May 2018, the UK government is pre-emptively undermining ours in these three bills.

Young people, and data dependent institutions, are asking for solutions to show what personal data is held where, and used by whom, for what purposes. That buys in the benefit message that builds trust showing what you said you’d do with my data, is what you did with my data. [1] [2]

Reality is that in post-truth politics it seems anything goes, on both sides of the Pond. So how will we trust what our data is used for?

2015-16 advice from the cross party Science and Technology Committee suggested data privacy is unsatisfactory, “to be left unaddressed by Government and without a clear public-policy position set out“. We hear the need for data privacy debated about use of consumer data, social media, and on using age verification. It’s necessary to secure the public trust needed for long term public benefit and for economic value derived from data to be achieved.

But the British government seems intent on shortsighted legislation which does entirely the opposite for its own use: in the Higher Education Bill, the Technical and Further Education Bill and in the Digital Economy Bill.

These bills share what Baroness Chakrabarti said of the Higher Education Bill in its Lords second reading on the 6th December, “quite an achievement for a policy to combine both unnecessary authoritarianism with dangerous degrees of deregulation.”

Unchecked these Bills create the conditions needed for catastrophic failure of public trust. They shift ever more personal data away from personal control, into the centralised control of the Secretary of State for unclear purposes and use by undefined third parties. They jeopardise the collection and integrity of public administrative data.

To future-proof the immediate integrity of student personal data collection and use, the DfE reputation, and public and professional trust in DfE political leadership, action must be taken on safeguards and oversight, and should consider:

- Transparency register: a public record of access, purposes, and benefits to be achieved from use

- Subject Access Requests: Providing the public ways to access copies of their own data

- Consent procedures should be strengthened for collection and cannot say one thing, and do another

- Ability to withdraw consent from secondary purposes should be built in by design, looking to GDPR from 2018

- Clarification of the legislative purpose of intended current use by the Secretary of State and its boundaries shoud be clear

- Future purpose and scope change limitations should require consultation – data collected today must not used quite differently tomorrow without scrutiny and ability to opt out (i.e. population wide registries of religion, ethnicity, disability)

- Review or sunset clause

If the legislation in these three bills pass without amendment, the potential damage to privacy will be lasting.

[1] http://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-question/Commons/2016-07-15/42942/ Parliamentary written question 42942 on the collection of pupil nationality data in the school census starting in September 2016: “what limitations will be placed by her Department on disclosure of such information to (a) other government departments?”

Schools Minister Nick Gibb responded on July 25th 2016: ”

“These new data items will provide valuable statistical information on the characteristics of these groups of children […] “The data will be collected solely for internal Departmental use for the analytical, statistical and research purposes described above. There are currently no plans to share the data with other government Departments”

[2] December 15, publication of MOU between the Home Office Casework Removals Team and the DfE, reveals “the previous agreement “did state that DfE would provide nationality information to the Home Office”, but that this was changed “following discussions” between the two departments.” http://schoolsweek.co.uk/dfe-had-agreement-to-share-pupil-nationality-data-with-home-office/

The agreement was changed on 7th October 2016 to not pass nationality data over. It makes no mention of not using the data within the DfE for the same purposes.