A duty of confidentiality and the regulation of medical records are as old as the hills. Public engagement on attitudes in this in context of the NHS has been done and published by established social science and health organisations in the last three years. So why is Google DeepMind (GDM) talking about it as if it’s something new? What might assumed consent NHS-wide mean in this new context of engagement? Given the side effects for public health and medical ethics of a step-change towards assumed consent in a commercial product environment, is this ‘don’t be evil’ shift to ‘do no harm’ good enough? Has Regulation failed patients?

My view from the GDM patient and public event, September 20.

Involving public and patients

Around a hundred participants joined the Google DeepMind public and patient event, in September after which Paul Wicks gave his view in the BMJ afterwards, and rightly started with the fact the event was held in the aftermath of some difficult questions.

Surprisingly, none were addressed in the event presentations. No one mentioned data processing failings, the hospital Trust’s duty of confidentiality, or criticisms in the press earlier this year. No one talked about the 5 years of past data from across the whole hospital or monthly extracts that were being shared and had first been extracted for GDM use without consent.

I was truly taken aback by the sense of entitlement that came across. The decision by the Trust to give away confidential patient records without consent earlier in 2015/16 was either forgotten or ignored and until the opportunity for questions, the future model was presented unquestioningly. The model for an NHS-wide hand held gateway to your records that the announcement this week embeds.

What matters on reflection is that the overall reaction to this ‘engagement’ is bigger than the one event, bigger than the concepts of tools they could hypothetically consider designing, or lack of consent for the data already used.

It’s a massive question of principle, a litmus test for future commercial users of big, even national population-wide public datasets.

Who gets a say in how our public data are used? Will the autonomy of the individual be ignored as standard, assumed unless you opt out, and asked for forgiveness with a post-haste opt out tacked on?

Should patients just expect any hospital can now hand over all our medical histories in a free-for-all to commercial companies and their product development without asking us first?

Public and patient questions

Where data may have been used in the algorithms of the DeepMind black box, there was a black hole in addressing patient consent.

Public engagement with those who are keen to be involved, is not a replacement for individual permission from those who don’t want to be, and who expected a duty of patient-clinician confidentiality.

Tellingly, the final part of the event tried to be a capture our opinions on how to involve the public. Right off the bat the first question was one of privacy. Most asked questions about issues raised to date, rather than looking to design the future. Ignoring those and retrofitting a one-size fits all model under the banner of ‘engagement’ won’t work until they address concerns of those people they have already used and the breach of trust that now jeopardises people’s future willingness to be involved, not only in this project, but potentially other research.

This event should have been a learning event for Google which is good at learning and uses people to do it both by man and machine.

But from their post-media reaction after this week’s announcement it seems not all feedback or lessons learned are welcome.

Google DeepMind executives were keen to use patient case studies and had patients themselves do the most talking, saying how important data is to treat kidney and eyecare, which I respect greatly. But there was very little apparent link why their experience was related to Google DeepMind at all or products created to date.

Google DeepMind has the data from every patient in the hospital in recent years, not only patients affected by this condition and not data from the people who will be supported directly by this app.

Yet GoogleDeepMind say this is “direct care” not research. Hard to be for direct care when you are no longer under the hospital’s care. Implied consent for use of sensitive health data, needs to be used in alignment with the purposes for which it was given. It must be fair and lawful.

If data users don’t get that, or won’t accept it, they should get out of healthcare and our public data right now. Or heed advice of critical friends and get it right to be trustworthy in future. .

What’s the plan ahead?

Beneath the packaging, this came across as a pitch on why Google DeepMind should get access to paid-for-by-the-taxpayer NHS patient data. They have no clinical background or duty of care. They say they want people to be part of a rigorous process, including a public/patient panel, but it’s a process they clearly want to shape and control, and for a future commercial model. Can a public panel be truly independent, and ethical, if profit plays a role?

Of course it’s rightly exciting for healthcare to see innovation and drives towards better clinical care, but not only the intent but how it gets done matters. This matters because it’s not a one-off.

The anticipation in the room of ‘if only we could access the whole NHS data cohort’ was tangible in the room, and what a gift it would be to commercial companies and product makers. Wrapped in heart wrenching stories. Stories of real-patients, with real-lives who genuinely want improvement for all. Who doesn’t want that? But hanging on the coat tails of Mr Suleyman were a range of commmercial companies and third party orgs asking for the same.

In order to deliver those benefits and avoid its risks there is well-established framework of regulation and oversight of UK practitioners and use of medical records and in medical devices and tools: the General Medical Council, the Health and Social Care Information Centre (Now called ‘NHS Digital’), Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG)and more, all have roles to play.

Google DeepMind and the Trusts have stepped outwith that framework and been playing catch up not only with public involvement, but also with MHRA regulatory approval.

One of the major questions is around the invisibility of data science decisions that have direct interventions in people’s life and death.

The ethics of data sciences in which decisions are automated, requires us to “guard against dangerous assumptions that algorithms are near-perfect, or more perfect than human judgement.” (The Opportunities and Ethics of Big Data. [1])

If Google DeepMind now plans to share their API widely who will proof their tech? Who else gets to develop something similar?

Don’t be evil 2.0

Google DeepMind appropriated ‘do no harm’ as the health event motto, echoing the once favored Google motto ‘don’t be evil’.

However, they really needed to address that the fragility of some patients’ trust in their clinicians has been harmed already, before DeepMind has even run an algorithm on the data, simply because patient data was given away without patients’ permission.

A former Royal Free patient spoke to me at the event and said they were shocked to have to have first read in the papers that their confidential medical records had been given to Google without their knowledge. Another said his mother had been part of the cohort and has concerns. Why weren’t they properly informed? The public engagement work they should to my mind be doing, is with the London hospital individual patients whose data they have already been using without their consent, explaining why they got their confidential medical records without telling them, and addressing their questions and real concerns. Not at a flash public event.

I often think in the name, they just left off the ‘e’. They are Google. We are the deep mined. That may sound flippant but it’s not the intent. It’s entirely serious. Past patient data was handed over to mine, in order to think about building a potential future tool.

There was a lot of if, future, ambition, and sweeping generalisations and ‘high-level sketches’ of what might be one day. You need moonshots to boost discovery, but losing patient trust even of a few people, cannot be a casualty we should casually accept. For the company there is no side effect. For patients, it could last a lifetime.

If you go back to the roots of health care, you could take the since misappropriated Hippocratic Oath and quote not only, as Suleyman did, “do no harm” , but the next part. “I will not play God.”

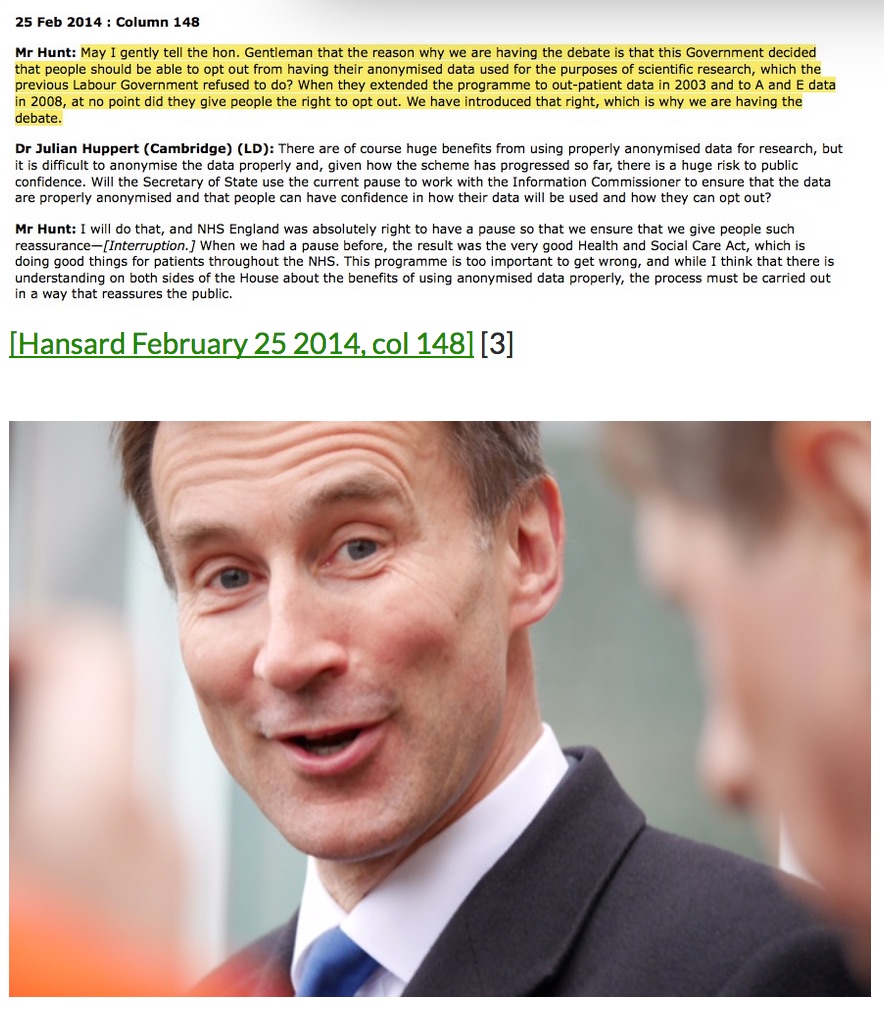

Patriarchal top down Care.data was a disastrous model of engagement that confused communication with ‘tell the public loudly and often what we want to happen, what we think best, and then disregard public opinion.’ A model that doesn’t work.

The recent public engagement event on the National Data Guardian work consent models certainly appear from the talks to be learning those lessons. To get it wrong in commercial use, will be disastrous.

The far greater risk from this misadventure is not company reputation, which seems to be top among Google DeepMind’s greatest concern. The risk that Google DeepMind seems prepared to take is one that is not at its cost, but that of public trust in the hospitals and NHS brand, public health, and its research.

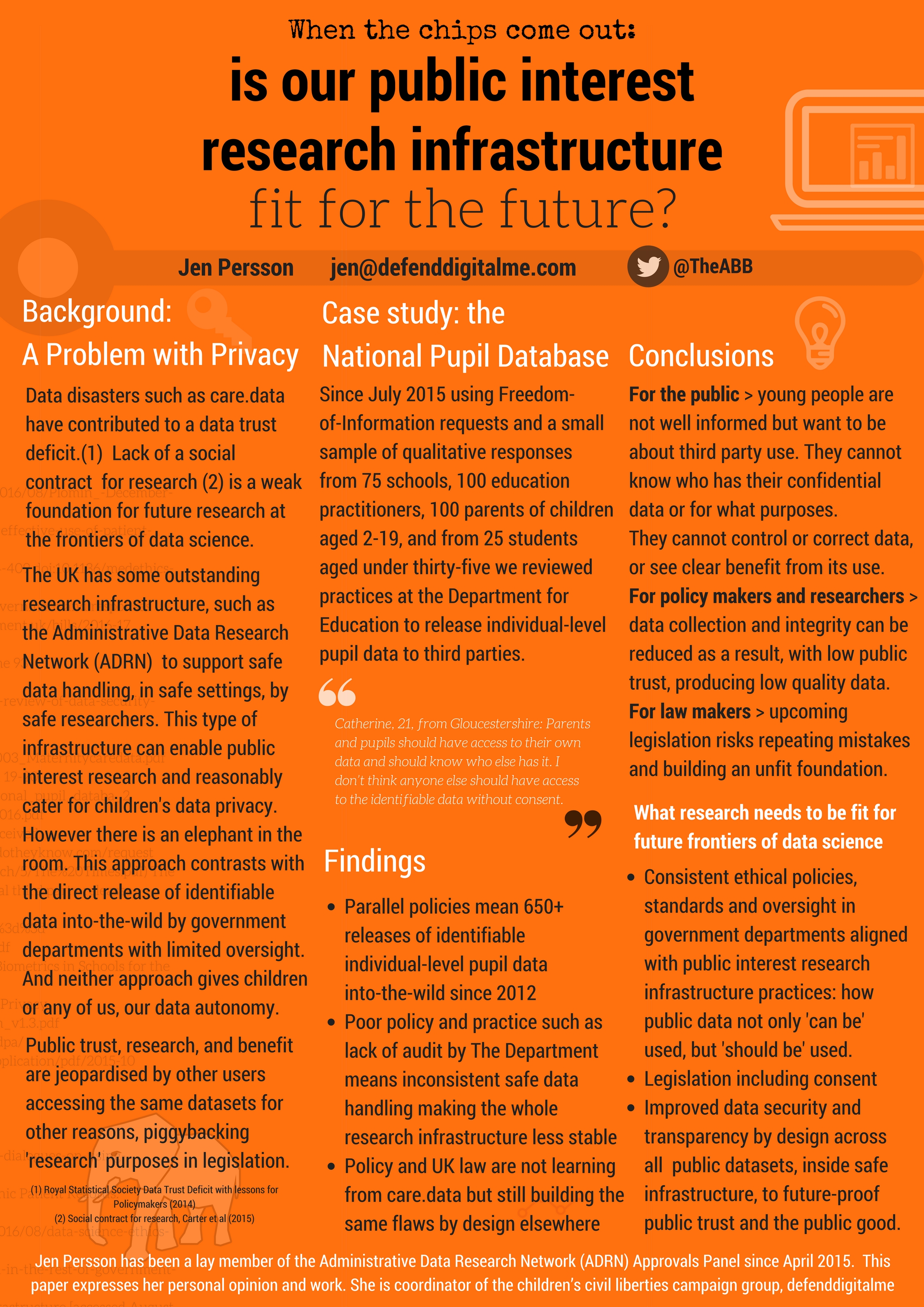

Commercial misappropriation of patient data without consent could set back restoration of public trust and work towards a better model that has been work-in-progress since care.data car crash of 2013.

You might be able to abdicate responsibility if you think you’re not the driver. But where does the buck stop for contributory failure?

All this, says Google DeepMind, is nothing new, but Google isn’t other companies and this is a massive pilot move by a corporate giant into first appropriating and then brokering access to NHS-wide data to make an as-yet opaque private profit. And being paid by the hospital trust to do so. Creating a data-sharing access infrastructure for the Royal Free is product development and one that had no permission to use 5 years worth of patient records to do so.

The care.data catastrophe may have damaged public trust and data access for public interest research for some time, but it did so doing commercial interests a massive favour. An assumption of ‘opt out’ rather than ‘opt in’ has become the NHS model. If the boundaries are changing of what is assumed under that, do the public still have no say in whether that is satisfactory? Because it’s not.

This example should highlight why an opt out model of NHS patient data is entirely unsatisfactory and cannot continue for these uses.

Should boundaries be in place?

So should boundaries in place in the NHS before this spreads. Hell yes. If as Mustafa said, it’s not just about developing technology but the process, regulatory and governance landscapes, then we should be told why their existing use of patient data intended for the Streams app development steam-rollered through those existing legal and ethical landscapes we have today. Those frameworks exist to preserve patients from quacks and skullduggery.

This then becomes about the duty of the controller and rights of the patient. It comes back to what we release, not only how it is used.

Can a panel of highly respected individuals intervene to embed good ethics if plans conflict with the purpose of making money from patients? Where are the boundaries between private and public good? Where they quash consent, where are its limitations and who decides? What boundaries do hospital trusts think they have on the duty of confidentiality?

It is for the hospitals as the data controllers from information received through their clinicians that responsibility lies.

What is next for Trusts? Giving an entire hospital patient database to supermarket pharmacies, because they too might make a useful tool? Mash up your health data with your loyalty card? All under assumed consent because product development is “direct care” because it’s clearly not research? Ethically it must be opt in.

App development is not using data for direct care. It is in product development. Post-truth packaging won’t fly. Dressing up the donkey by simply calling it by another name, won’t transform it into a unicorn, no matter how much you want to believe in it.

“In some sense I recognise that we’re an exceptional company, in other senses I think it’s important to put that in the wider context and focus on the patient benefit that we’re obviously trying to deliver.” [TechCrunch, November 22]

We’ve heard the cry, to focus on the benefit before. Right before care.data failed to communicate to 50m people what it was doing with their health records. Why does Google think they’re different? They don’t. They’re just another company normalising this they say.

The hospitals meanwhile, have been very quiet.

What do patients want?

This was what Google DeepMind wanted to hear in the final 30 minutes of the event, but didn’t get to hear as all the questions were about what have you done so far and why?

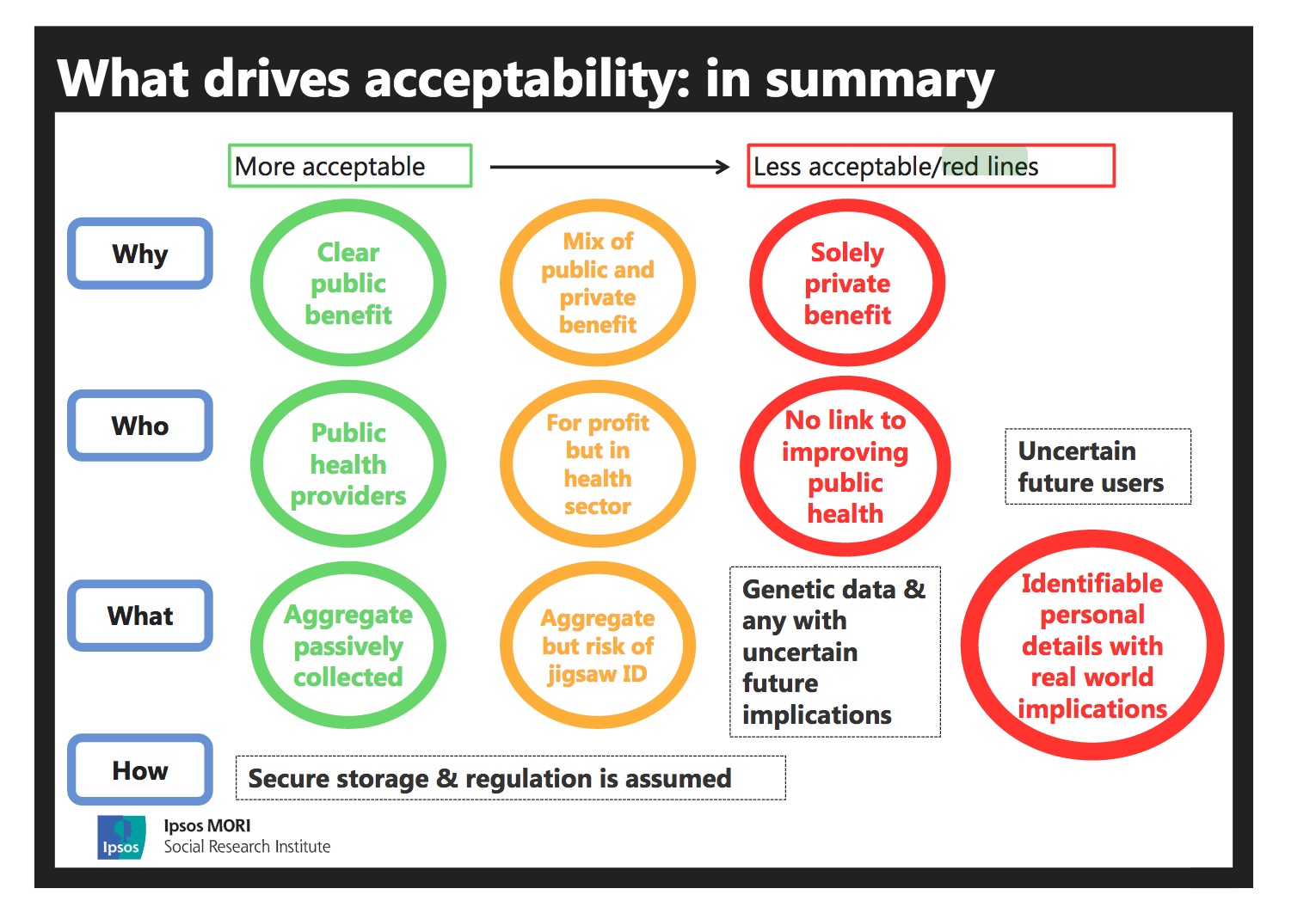

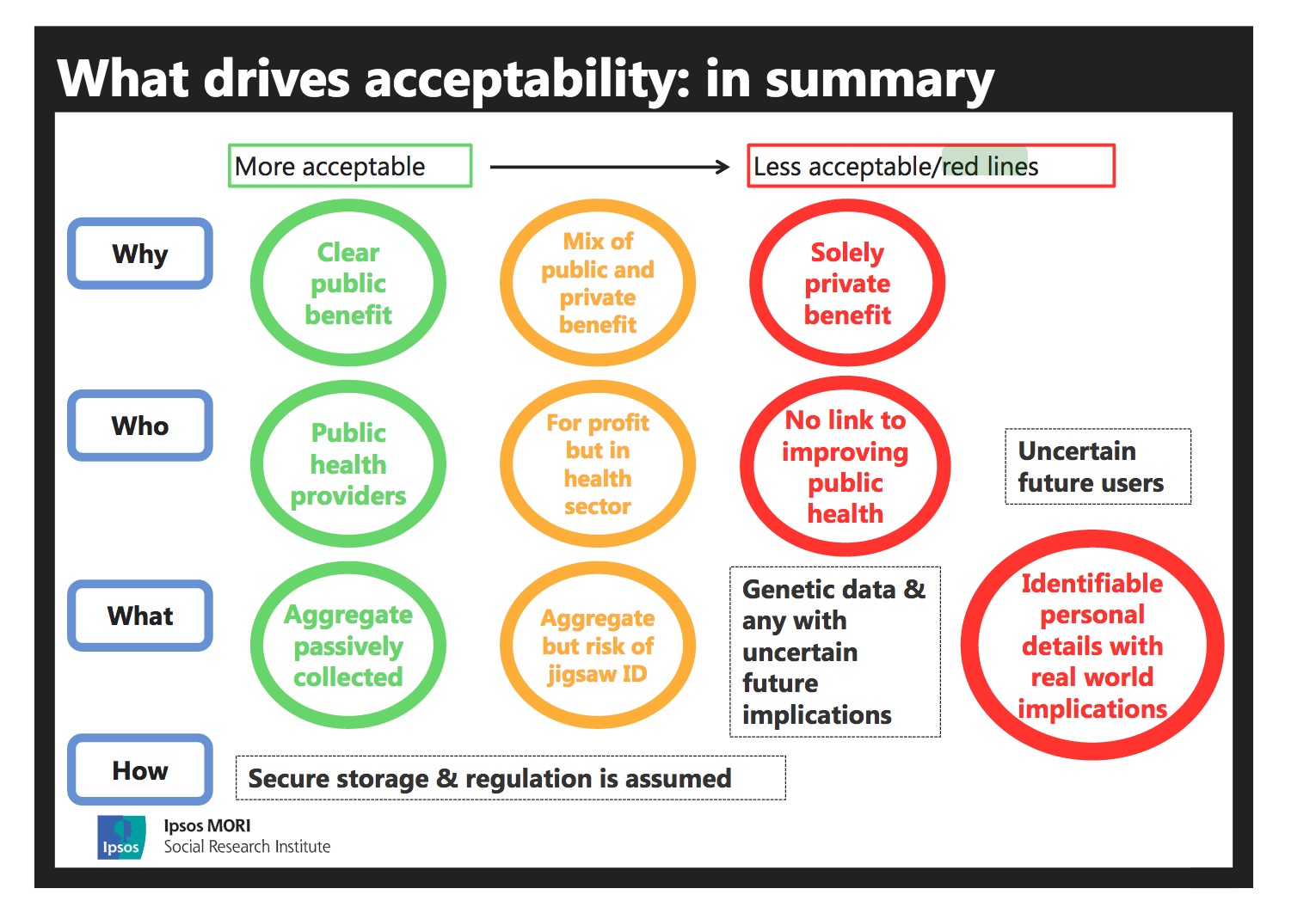

There is already plenty of evidence what the public wants on the use of their medical records, from public engagement work that has already been done around NHS health data use from workshops and surveys since 2013. Public opinion is pretty clear. Many say companies should not get NHS records for commercial exploitation without consent at all (in the ESRC public dialogues on data in 2013, the Royal Statistical Society’s data trust deficit with lessons for policy makers work with Ipsos MORI in 2014, and the Wellcome Trust one-way mirror work in 2016 as well of course as the NHS England care.data public engagement workshops in 2014).

All those surveys and workshops show the public have consistent levels of concern about having a lack of control over who has access to their NHS data for what purposes and unlimited scope or future, and commercial purposes of their data is a red-line for many people.

A red-line which this Royal Free Google DeepMind project appeared to want to wipe out as if it had never been drawn at all.

I am sceptical that Google DeepMind has not done their research into existing public opinion on health data uses and research.

Those studies in public engagement already done by leading health and social science bodies state clearly that commercial use is a red line for some.

So why did they cross it without consent? Tell me why I should trust the hospitals to get this right with this company but trust you not to get it wrong with others. Because Google’s the good guys?

If this event and thinking ‘let’s get patients to front our drive towards getting more data’ sought to legitimise what they and these London hospitals are already getting wrong, I’m not sure that just ‘because we’re Google’ being big, bold and famous for creative disruption, is enough. This is a different game afoot. It will be a game-changer for patient rights to privacy if this scale of commercial product exploitation of identifiable NHS data becomes the norm at a local level to decide at will. No matter how terrific the patient benefit should be, hospitals can’t override patient rights.

If this steamrollers over consent and regulations, what next?

Regulation revolutionised, reframed or overruled

The invited speaker from Patients4Data spoke in favour of commercial exploitation as a benefit for the NHS but as Paul Wicks noted, was ‘perplexed as to why “a doctor is worried about crossing the I’s and dotting the T’s for 12 months (of regulatory approval)”.’

Appropriating public engagement is one thing. Appropriating what is seen as acceptable governance and oversight is another. If a new accepted model of regulation comes from this, we can say goodbye to the old one. Goodbye to guaranteed patient confidentiality. Goodbye to assuming your health data are not open to commercial use. Hello to assuming opt out of that use is good enough instead.

Trusted public regulatory and oversight frameworks exist for a reason. But they lag behind the industry and what some are doing. And if big players can find no retribution in skipping around them and then being approved in hindsight there’s not much incentive to follow the rules from the start. As TechCrunch suggested after the event, this is all “pretty standard playbook for tech firms seeking to workaround business barriers created by regulation.”

Should patients just expect any hospital can now hand over all our medical histories in a free-for-all to commercial companies without asking us first? It is for the Information Commissioner to decide whether the purposes of product design were what patients expected their data to be used for, when treated 5 years ago.

The state needs to catch up fast. The next private appropriation of the regulation of AI collaboration oversight, has just begun. Until then, I believe civil society will not be ‘pedalling’ anything, but I hope will challenge companies cheek by jowl in any race to exploit personal confidential data and universal rights to privacy [2] by redesigning regulation on company terms.

Let’s be clear. It’s not direct care. It’s not research. It’s product development. For a product on which the commercial model is ‘I don’t know‘. How many companies enter a 5 year plan like that?

Benefit is great. But if you ignore the harm you are doing in real terms to real lives and only don’t see it because they’ve not talked to you, ask yourself why that is, not why you don’t believe it matters.

There should be no competition in what is right for patient care and data science and product development. The goals should be the same. Safe uses of personal data in ways the public expect, with no surprises. That means consent comes first in commercial markets.

[1] Olivia Varley-Winter, Hetan Shah, ‘The opportunities and ethics of big data: practical priorities for a national Council of Data Ethics.’ Theme issue ‘The ethical impact of data science’ compiled and edited by Mariarosaria Taddeo and Luciano Floridi. [The Royal Society, Volume 374, issue 2083]

[2] Universal rights to privacy: Upcoming Data Protection legislation (GDPR) already in place and enforceable from May 25, 2018 requires additional attention to fair processing, consent, the right to revoke it, to access one’s own and seek redress for inaccurate data. “The term “child” is not defined by the GDPR. Controllers should therefore be prepared to address these requirements in notices directed at teenagers and young adults.”

The Rights of the Child: Data policy and practice about children’s confidential data will impinge on principles set out in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 12, the right to express views and be heard in decisions about them and Article 16 a right to privacy and respect for a child’s family and home life if these data will be used without consent. Similar rights that are included in the common law of confidentiality.

Article 8 of the Human Rights Act 1998 incorporating the European Convention on Human Rights Article 8.1 and 8.2 that there shall be no interference by a public authority on the respect of private and family life that is neither necessary or proportionate.

Judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Bara case (C‑201/14) (October 2015) reiterated the need for public bodies to legally and fairly process personal data before transferring it between themselves. Trusts need to respect this also with contractors.

The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, Article 52 also protects the rights of individuals about data and privacy and Article 52 protects the essence of these freedoms.