Demonstrable value of public research to the public good, while abstract, is a concept quite clearly understood.

Demonstrating the economic value of data for private consumer companies like major supermarkets is even easier to understand.

What is less obvious is the harm that the commercial misuse of data can do to the public’s perception of all research for the public good.[6]

The personal cost of consumer data exploitation, whether through the loss of, or through paid-for privacy, must be limited to reduce the perceived personal cost of the public good.

By reducing the personal cost, we increase the value of the perceived public benefit of sharing and overall public good.

The public good may mean many things: benefits from public health research like understanding how disease travels, or good financial planning, derived from knowing what needs communities have and what services to provide.

By reducing the private cost to individuals of the loss of control and privacy of our data, citizens will be more willing to share.

It will create more opportunity for data to be used in the public interest, for both economic and social gain.

As I outlined in the previous linked blog posts, consent [part 1] and privacy [part 2] would be wise investments for its growth.

So how are consumer businesses and the state taking this into account?

Where is the dialogue we need to keep expectations and practices aligned in a changing environment and legal framework?

Personalisation: the economic value of data for companies

Any projects under discussion or in progress without adequate public consultation and real involvement, that ignore public voice, risk their own success and with it the public good they should create.

The same is true for commercial projects. For example, back to Tesco.

Whether the clubcard data management and processing [8] is directly or indirectly connected to Tesco, its customer data are important to the supermarket chain and are valuable.

Former Tesco executive, spoke about that value in a 2013 interview:

“These are slow-growing industries,” Leahy said. “The difference was in the use of data, in the way Tesco learned about its customers. And from that, everything flowed.”[9]

By knowing who, how and when citizens shop, it allows them to target the sales offering to make people buy more or differently. The so-called ‘nudge’ moving citizens in the direction the company wants.

He explained how, through the Clubcard loyalty program, the supermarket was able to transition from mass marketing to personalized marketing and that it works in other areas too:

“You can already see in some areas where customers are content to be priced as customers: risk pricing with insurance and so on.

“It makes a lot of sense in health pricing, but there will be certain social policy restriction in terms of fair access and so on.”

NHS patient data and commercial supermarket data may be coming closer in their use than we might think.

Not only closer in their similar desire to move towards personalisation [10] but for similar reasons, in the desire to use all the data to know all about people as health consumers and from that, to plan and purchase, best and cheapest…”in reducing overall cost.”

It is worth thinking about in an economy driven by ideological austerity, how reducing overall cost will be applied, by cutting services or reducing to whom services are offered.

What ‘nudge’ may be applied through NHS policies, to move citizens in the direction the drivers in government or civil service want to see?

What will push those who can afford it, into private care and out of those who the state has to spend money on, if they are prepared to spend their own, for example.

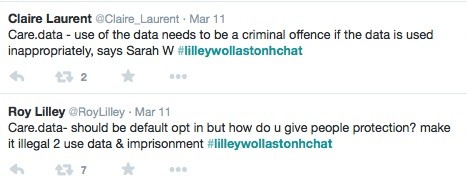

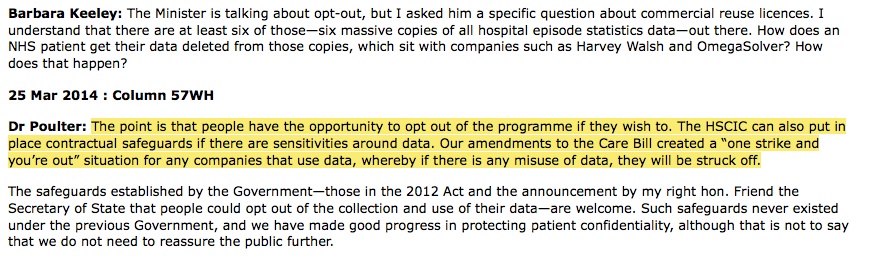

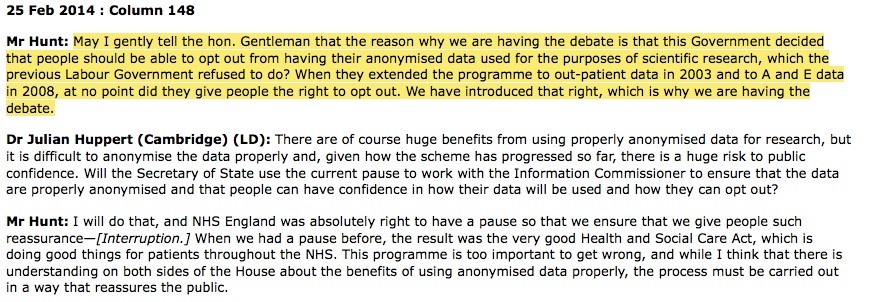

What is the data that citizens provide through schemes like care.data designed to achieve?

“Demonstrating The Actual Economic Value of Data”

Tim Kelsey, speaking at Strata in 2013 [11] talked about: “Demonstrating The Actual Economic Value of Data”. Our NHS data are valuable in both economic and social terms.

[From 12:17] “It will help put the UK on the map in terms of genomic research. The PM has already committed to the UK developing 100K gene sequences very rapidly. But those sequences on their own will have very limited value without the reference data that lies out there in the real world of the NHS, the data we’ll start making available form next June […]. The name of the programme by the way is care dot data.”

The long since delayed care.data programme plans to provide medical records for secondary use, as reference data for the 100K genomics programme. The programme has the intent to “create a lasting legacy for patients, the NHS and the UK economy.”

With consent.

When the CEO of Illumina talks about winning a US $20bn market [12] perhaps it also sounds economically appealing for the UK plc and the austerity-lean NHS. Illumina is the company which won the contract for the Genomics England project sequencing of course.

“The notion here is that it’s really a precursor to understand the health economics of why sequencing helps improve healthcare, both in quality of outcome, and in reducing overall cost. Presuming we meet the objectives of this three-year study–and it’s truly a pilot–then the program will expand substantially and sequence many more people in the U.K.” [Jay Flatley, CEO]

The idea of it being a precursor leaves me asking, to what?

“Will expand substantially” to whom?

As more and more becomes possible in science, there will be an ever greater need for understanding between how and why we should advance medicine, and how to protect human dignity. Because it becomes possible may not always mean it should be done.

Article 21 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the application of biology and medicine, also says: “The human body and its parts shall not, as such, give rise to financial gain.”

How close is profit making from DNA sequencing getting to that line?

These are questions that raise ethical questions and questions of social and economic value. The social legitimacy of these programmes will depend on trust. Trust based on no surprises.

Commercial market research or real research for the public good?

Meanwhile all consenting patients can in theory now choose to access their own record [GP online]. Mr Kelsey expressed hopes in 2013 that developers would use that to help patients:

“to mash it up with other data sources to get their local retailers to tell them about their purchasing habits [16:05] so they can mash it up with their health data.”

This despite the 67% of the public concerned around health data use by commercial companies.

So what were the commercially sensitive projects discussed by NHS England and Tesco throughout 2014? It would be interesting to know whether loyalty cards and mashing up our data was part of it – or did they discuss market segmentation, personalisation and health pricing? Will we hear the ‘Transparency Tsar‘ tell NHS citizens their engagement is valued, but in reality find the public is not involved?

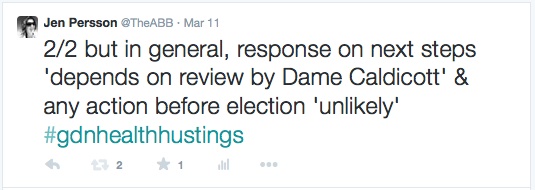

To do so would risk another care.data style fiasco in other fields.

Who might any plans offer most value to – the customer, the company or the country plc? Will the Goliaths focus on short term profit or fair processing and future benefits?

In the long run, ignoring public voice won’t help the UK plc or the public interest.

A balanced and sustainable research future will not centre on a consumer pay-for-privacy basis, or commercial alliances, but on a robust ethical framework for the public good.

A public good which takes profit into account for private companies and the state, but not at the expense of public feeling and ethical good practice.

A public good which we can understand in terms of social, direct and indirect economic value.

While we strive for the economic and public good in scientific and medical advances we must also champion human dignity and values.

This dialogue needs to be continued.

“The commitment must be an ongoing one to continue to consult with people, to continue to work to optimally protect both privacy and the public interest in the uses of health data. We need to use data but we need to use it in ways that people have reason to accept. Use ‘in the public interest’ must respect individual privacy. The current law of data protection, with its opposed concepts of ‘privacy’ and ‘public interest’, does not do enough to recognise the dependencies or promote the synergies between these concepts.”

[M Taylor, “Information Governance as a Force for Good? Lessons to be Learnt from Care.data”, (2014) 11:1 SCRIPTed 1]

The public voice from care.data listening and beyond, could positively help shape the developing consensual model if given genuine adequate opportunity to do so in much needed dialogue.

As they say, every little helps.

****

Part one: The Economic Value of Data vs the Public Good? [1] Concerns and the cost of Consent

Part two: The Economic Value of Data vs the Public Good? [2] Pay-for-privacy and Defining Purposes.

Part three: The Economic Value of Data vs the Public Good? [3] The value of public voice.

****

[1] care.data listening event questions: https://jenpersson.com/pathfinder/

[2] Private Eye – on Tesco / NHS England commercial meetings https://twitter.com/medConfidential/status/593819474807148546

[3] HSCIC audit and programme for change www.hscic.gov.uk/article/4780/HSCIC-learns-lessons-of-the-past-with-immediate-programme-for-change

[4] EU data protection discussion http://www.digitalhealth.net/news/EHI/9934/eu-ministers-back-data-privacy-changes

[5] Joint statement on EU Data Protection proposals http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/stellent/groups/corporatesite/@policy_communications/documents/web_document/WTP055584.pdf

[6] Ipsos MORI research with the Royal Statistical Society into the Trust deficit with lessons for policy makers https://www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/3422/New-research-finds-data-trust-deficit-with-lessons-for-policymakers.aspx

[7] AdExchanger Janaury 2015 http://adexchanger.com/data-driven-thinking/the-newest-asset-class-data/

[8] Tesco clubcard data sale https://jenpersson.com/public_data_in_private_hands/ / Computing 14.01.2015 – article by Sooraj Shah: http://www.computing.co.uk/ctg/feature/2390197/what-does-tescos-sale-of-dunnhumby-mean-for-its-data-strategy

[9] Direct Marketing 2013 http://www.dmnews.com/tesco-every-little-bit-of-customer-data-helps/article/317823/

[10] Personalisation in health data plans http://www.england.nhs.uk/iscg/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2014/01/ISCG-Paper-Ref-ISCG-009-002-Adult-Social-Care-Informatics.pdf

[11] Tim Kelsey Keynote speech at Strata November 2013 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s8HCbXsC4z8

[12] Forbes: Illumina CEO on the US$20bn DNA market http://www.forbes.com/sites/luketimmerman/2015/04/29/qa-with-jay-flatley-ceo-of-illumina-the-genomics-company-pursuing-a-20b-market/

![The Economic Value of Data vs the Public Good? [3] The value of public voice.](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Trust-e1426443553441-672x372.jpg)

![Wearables: patients will ‘essentially manage their data as they wish’. What will this mean for diagnostics, treatment and research and why should we care? [#NHSWDP 3]](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/FullSizeRender1-672x372.jpg)

![smartphones: the single most important health treatment & diagnostic tool at our disposal [#NHSWDP 2]](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/IMG_4563-e1427130930127-672x372.jpg)

![Thoughts on Digital Participation and Health Literacy: Opportunities for engaging citizens in the NHS [#NHSWDP 1]](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/FullSizeRender-640x372.jpg)