The Joint Committee on Human Rights report, The Right to Privacy (Article 8) and the Digital Revolution, calls for robust regulation to govern how personal data is used and stringent enforcement of the rules.

“The consent model is broken” was among its key conclusions.

Similarly, this summer, the Swedish DPA found, in accordance with GDPR, that consent was not a valid legal basis for a school pilot using facial recognition to keep track of students’ attendance given the clear imbalance between the data subject and the controller.

This power imbalance is at the heart of the failure of consent as a lawful basis under Art. 6, for data processing from schools.

Schools, children and their families across England and Wales currently have no mechanisms to understand which companies and third parties will process their personal data in the course of a child’s compulsory education.

Children have rights to privacy and to data protection that are currently disregarded.

- Fair processing is a joke.

- Unclear boundaries between the processing in-school and by third parties are the norm.

- Companies and third parties reach far beyond the boundaries of processor, necessity and proportionality, when they determine the nature of the processing: extensive data analytics, product enhancements and development going beyond necessary for the existing relationship, or product trials.

- Data retention rules are as unrespected as the boundaries of lawful processing. and ‘we make the data pseudonymous / anonymous and then archive / process / keep forever’ is common.

- Rights are as yet almost completely unheard of for schools to explain, offer and respect, except for Subject Access. Portability for example, a requirement for consent, simply does not exist.

In paragraph 8 of its general comment No. 1, on the aims of education, the UN Convention Committee on the Rights of the Child stated in 2001:

“Children do not lose their human rights by virtue of passing through the school gates. Thus, for example, education must be provided in a way that respects the inherent dignity of the child and enables the child to express his or her views freely in accordance with article 12, para (1), and to participate in school life.”

Those rights currently unfairly compete with commercial interests. And that power balance in education is as enormous, as the data mining in the sector. The then CEO of Knewton, Jose Ferreira said in 2012,

“the human race is about to enter a totally data mined existence…education happens to be today, the world’s most data mineable industry– by far.”

At the moment, these competing interests and the enormous power imbalance between companies and schools, and schools and families, means children’s rights are last on the list and oft ignored.

In addition, there are serious implications for the State, schools and families due to the routine dependence on key systems at scale:

- Infrastructure dependence ie Google Education

- Hidden risks [tangible and intangible] of freeware

- Data distribution at scale and dependence on third party intermediaries

- and not least, the implications for families’ mental health and stress thanks to the shift of the burden of school back office admin from schools, to the family.

It’s not a contract between children and companies either

Contract GDPR Article 6 (b) does not work either, as a basis of processing between the data processing and the data subject, because again, it’s the school that determines the need for and nature of the processing in education, and doesn’t work for children.

The European Data Protection Board published Guidelines 2/2019 on the processing of personal data under Article 6(1)(b) GDPR in the context of the provision of online services to data subjects, on October 16, 2019.

Controllers must, inter alia, take into account the impact on data subjects’ rights when identifying the appropriate lawful basis in order to respect the principle of fairness.

They also concluded that, on the capacity of children to enter into contracts, (footnote 10, page 6)

“A contractual term that has not been individually negotiated is unfair under the Unfair Contract Terms Directive “if, contrary to the requirement of good faith, it causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract, to the detriment of the consumer”.

Like the transparency obligation in the GDPR, the Unfair Contract Terms Directive mandates the use of plain, intelligible language.

Processing of personal data that is based on what is deemed to be an unfair term under the Unfair Contract Terms Directive, will generally not be consistent with the requirement under Article5(1)(a) GDPR that processing is lawful and fair.’

In relation to the processing of special categories of personal data, in the guidelines on consent, WP29 has also observed that Article 9(2) does not recognize ‘necessary for the performance of a contract’ as an exception to the general prohibition to process special categories of data.

They too also found:

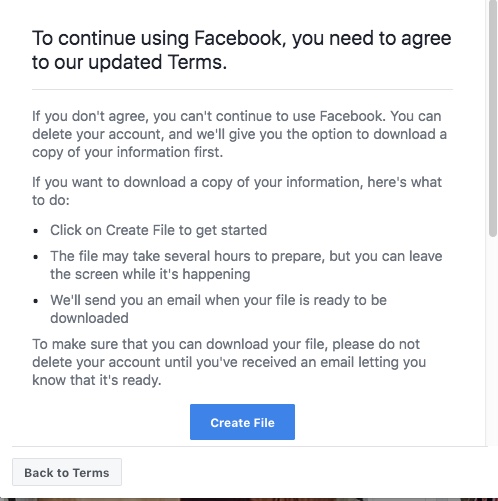

it is completely inappropriate to use consent when processing children’s data: children aged 13 and older are, under the current legal framework, considered old enough to consent to their data being used, even though many adults struggle to understand what they are consenting to.

Can we fix it?

Consent models fail school children. Contracts can’t be between children and companies. So what do we do instead?

Schools’ statutory tasks rely on having a legal basis under data protection law, the public task lawful basis Article 6(e) under GDPR, which implies accompanying lawful obligations and responsibilities of schools towards children. They cannot rely on (f) legitimate interests. This 6(e) does not extend directly to third parties.

Third parties should operate on the basis of contract with the school, as processors, but nothing more. That means third parties do not become data controllers. Schools stay the data controller.

Where that would differ with current practice, is that most processors today stray beyond necessary tasks and become de facto controllers. Sometimes because of the everyday processing and having too much of a determining role in the definition of purposes or not allowing changes to terms and conditions; using data to develop their own or new products, for extensive data analytics, the location of processing and data transfers, and very often because of excessive retention.

Although the freedom of the mish-mash of procurement models across UK schools on an individual basis, learning grids, MATs, Local Authorities and no-one-size-fits-all model may often be a good thing, the lack of consistency today means your child’s privacy and data protection are in a postcode lottery. Instead we need:

- a radical rethink the use of consent models, and home-school agreements to obtain manufactured ‘I agree’ consent.

- to radically articulate and regulate what good looks like, for interactions between children and companies facilitated by schools, and

- radically redesign a contract model which enables only that processing which is within the limitations of a processors remit and therefore does not need to rely on consent.

It would mean radical changes in retention as well. Processors can only process for only as long as the legal basis extends from the school. That should generally be only the time for which a child is in school, and using that product in the course of their education. And certainly data must not stay with an indefinite number of companies and their partners, once the child has left that class, year, or left school and using the tool. Schools will need to be able to bring in part of the data they outsource to third parties for learning, *if* they need it as evidence or part of the learning record, into the educational record.

Where schools close (or the legal entity shuts down and no one thinks of the school records [yes, it happens], change name, and reopen in the same walls as under academisation) there must be a designated controller communicated before the change occurs.

The school fence is then something that protects the purposes of the child’s data for education, for life, and is the go to for questions. The child has a visible and manageable digital footprint. Industry can be confident that they do indeed have a lawful basis for processing.

Schools need to be within a circle of competence

This would need an independent infrastructure we do not have today, but need to draw on.

- Due diligence,

- communication to families and children of agreed processors on an annual basis,

- an opt out mechanism that works,

- alternative lesson content on offer to meet a similar level of offering for those who do,

- and end-of-school-life data usage reports.

The due diligence in procurement, in data protection impact assessment, and accountability needs to be done up front, removed from the classroom teacher’s responsibility who is in an impossible position having had no basic teacher training in privacy law or data protection rights, and the documents need published in consultation with governors and parents, before beginning processing.

However, it would need to have a baseline of good standards that simply does not exist today.

That would also offer a public safeguard for processing at scale, where a company is not notifying the DPA due to small numbers of children at each school, but where overall group processing of special category (sensitive) data could be for millions of children.

Where some procurement structures might exist today, in left over learning grids, their independence is compromised by corporate partnerships and excessive freedoms.

While pre-approval of apps and platforms can fail where the onus is on the controller to accept a product at a point in time, the power shift would occur where products would not be permitted to continue processing without notifying of significant change in agreed activities, owner, storage of data abroad and so on.

We shift the power balance back to schools, where they can trust a procurement approval route, and children and families can trust schools to only be working with suppliers that are not overstepping the boundaries of lawful processing.

What might school standards look like?

The first principles of necessity, proportionality, data minimisation would need to be demonstrable — just as required under data protection law for many years, and is more explicit under GDPR’s accountability principle. The scope of the school’s authority must be limited to data processing for defined educational purposes under law and only these purposes can be carried over to the processor. It would need legislation and a Code of Practice, and ongoing independent oversight. Violations could mean losing the permission to be a provider in the UK school system. Data processing failures would be referred to the ICO.

- Purposes: A duty on the purposes of processing to be for necessary for strictly defined educational purposes.

- Service Improvement: Processing personal information collected from children to improve the product would be very narrow and constrained to the existing product and relationship with data subjects — i.e security, not secondary product development.

- Deletion: Families and children must still be able to request deletion of personal information collected by vendors which do not form part of the permanent educational record. And a ‘clean slate’ approach for anything beyond the necessary educational record, which would in any event, be school controlled.

- Fairness: Whilst at school, the school has responsibility for communication to the child and family how their personal data are processed.

- Post-school accountability as the data, resides with the school: On leaving school the default for most companies, should be deletion of all personal data, provided by the data subject, by the school, and inferred from processing. For remaining data, the school should become the data controller and the data transferred to the school. For any remaining company processing, it must be accountable as controller on demand to both the school and the individual, and at minimum communicate data usage on an annual basis to the school.

- Ongoing relationships: Loss of communication channels should be assumed to be a withdrawal of relationship and data transferred to the school, if not deleted.

- Data reuse and repurposing for marketing explicitly forbidden. Vendors must be prohibited from using information for secondary [onward or indirect] reuse, for example in product or external marketing to pupils or parents.

- Families must still be able to object to processing, on an ad hoc basis, but at no detriment to the child, and an alternative method of achieving the same aims must be offered.

- Data usage reports would become the norm to close the loop on an annual basis. “Here’s what we said we’d do at the start of the year. Here’s where your data actually went, and why.”

- In addition, minimum acceptable ethical standards could be framed around for example, accessibility, and restrictions on in-product advertising.

There must be no alternative back route to just enough processing

What we should not do, is introduce workarounds by the back door.

Schools are not to carry on as they do today, manufacturing ‘consent’ which is in fact unlawful. It’s why Google, despite the objection when I set this out some time ago, is processing unlawfully. They rely on consent that simply cannot and does not exist.

The U.S. schools model wording would similarly fail GDPR tests, in that schools cannot ‘consent’ on behalf of children or families. I believe that in practice the US has weakened what should be strong protections for school children, by having the too expansive “school official exception” found in the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (“FERPA”), and as described in Protecting Student Privacy While Using Online Educational Services: Requirements and Best Practices.

Companies can also work around their procurement pathways.

In parallel timing, the US Federal Trade Commission’s has a consultation open until December 9th, on the Implementation of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule, the COPPA consultation.

‘There has been a significant expansion of education technology used in classrooms’, the FTC mused before asking whether the Commission should consider a specific exception to parental consent for the use of education technology used in the schools.

In a backwards approach to agency and the development of a rights respecting digital environment for the child, the consultation in effect suggests that we mould our rights mechanisms to fit the needs of business.

That must change. The ecosystem needs a massive shift to acknowledge that if it is to be GDPR compliant, which is a rights respecting regulation, then practice must become rights respecting.

That means meeting children and families reasonable expectations. If I send my daughter to school, and we are required to use a product that processes our personal data, it must be strictly for the *necessary* purposes of the task that the school asks of the company, and the child/ family expects, and not a jot more.

Borrowing on Ben Green’s smart enough city concept, or Rachel Coldicutt’s just enough Internet, UK school edTech suppliers should be doing just enough processing.

How it is done in the U.S. governed by FERPA law is imperfect and still results in too many privacy invasions, but it offers a regional model of expertise for schools to rely on, and strong contractual agreements of what is permitted.

That, we could build on. It could be just enough, to get it right.