I’ve been inspired by many people this week.

Shakespeare who is long dead. Another, less famous, we celebrated at her funeral after only a few weeks of living with diagnosed endocrine cancer. She would have turned 76 this week.

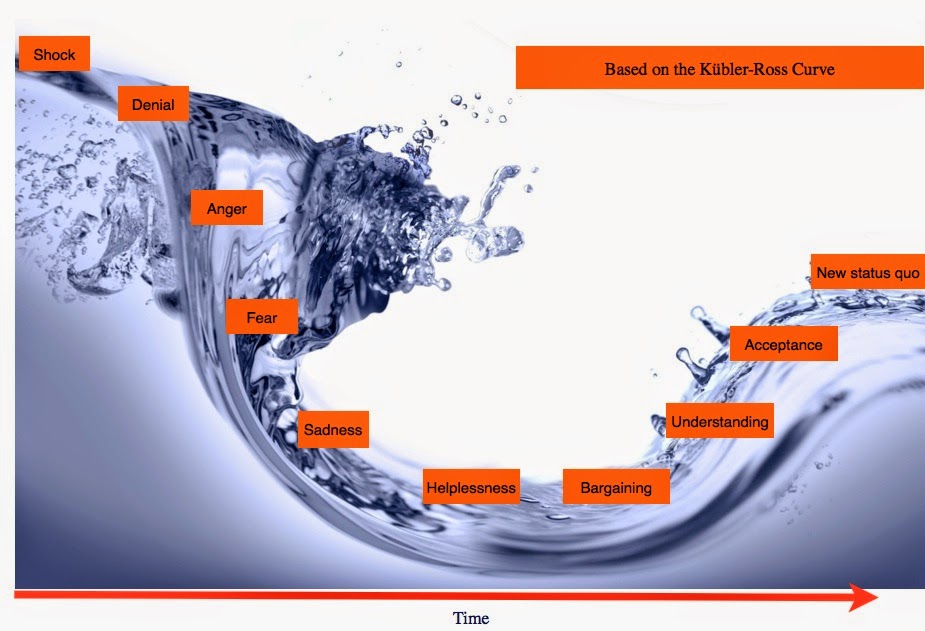

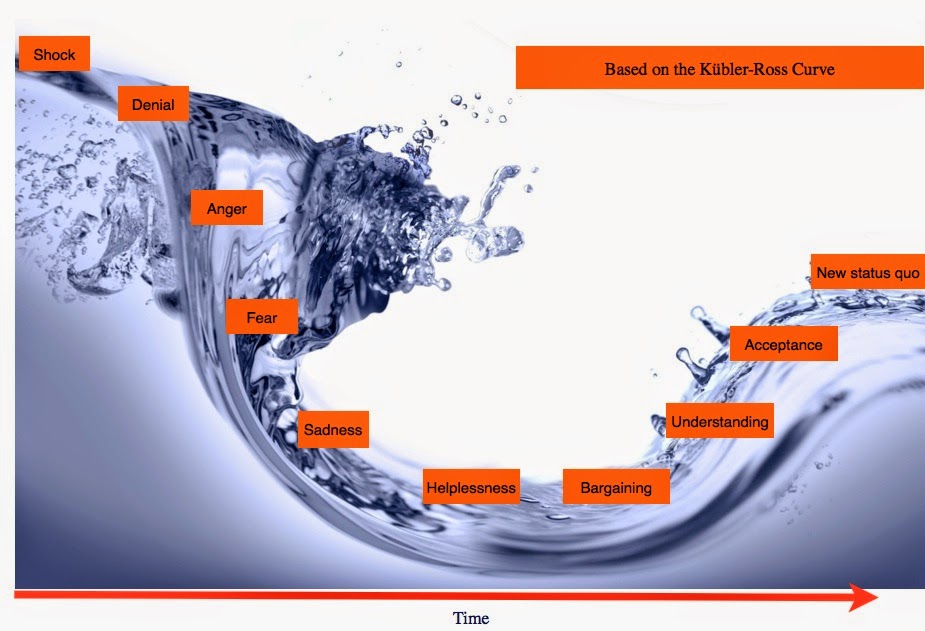

The change curve

How do we deal with change?

Anyone familiar with the theory of grief, or more happily (as I am from my previous professional life) the similar theory for managing change, knows the stages along the curve we need to go through, to reach a new status quo after a process of adjustment.

After the initial shock and denial, there may be anger, frustration and fear before any acceptance or new optimism is possible.

Individuals follow the curve at their own pace. Some may not go through each stage. Others may simply be too upset, disagree early, give up with or repel the change, and never reach a comfortable position or commitment to a new status quo.

Whether it is grief or a business change, the natural initial response is emotional, and starts with loss. Loss of a person, of position, of something we cannot control. It can take a great deal of support, time and good communication to go through the journey.

(And yes, there’s a comms lesson for care.data in here.)

Before we begin on a change we need to understand the point from where we are starting. And crucially, to understand that Change is about people, not technology or business process.

The change curve starts with shock

From many people’s perspective, the concept of care.data, has been a shock.

For those working on the project, or at NHS England, that is probably hard to understand. ‘Why on earth all the fuss?’, they may ask. It’s easier to understand, if you realise the majority of the public had no idea at all, our health data was used for anything other than our direct care and some planning. Much less may have been winging its way on the cloud across the Atlantic. It feels like data theft.

It’s easy for those in a technology project to see ‘coded’ health records simply as data.

‘Coded’ is however like saying we speak the ‘French language’. Computers ‘only speak’ code, so telling the public it is coded is either trying naively to make it sound safer than as if ‘plain language’ was sent from the GP system to the central system, or it is misleading.

In the same way, if you say ‘opt out’ the system records ‘9Nu4’ on your record. In addition, there will be a label to go with it, so if GPs run a report to find everyone who has opted out, they can. It’s not hard to understand that MOTDOB is mother’s date of birth. There is a full public dictionary of these codes.

NHS England and the project team, should also not forget that this is not just ‘data’.

To us, this is our irrevocable health and social imprint. Signposts to who we are, have been and perhaps, will be.

It’s personal and private. And as yet, we may have only shared those facts with our GP. Only our GP and not yet our partners, or parents. And then we find out global Health Intelligence companies might have our sexuality or pregnancy history, conditions we may not have told anyone but the GP. Data intermediaries may have complete picture of prescribed medicines, drawing on information from 100,000 suppliers, and on insights from billions of annual healthcare transactions. “mountains of data from pharmacies, insurance claims, medical records, partners and other sources, 17 petabytes of data spread across 5,000 databases.” We want data used by the right people for the right reasons, and know where it goes and why.

HSCIC is giving it away almost for free.

To them it may be only data. To us it’s intimate.

But for the three of us in this marriage, it’s information which has been used and shared with these third parties, and as far as we can see, only one of us really benefits from the deal. Identifiable or not, is only part of the story. It’s our biography we did not give you permission to read or tell.

The initial shock, fears, anxiety and general disgust that our personal details are sold (sorry) given away on a cost recovery basis charging to cover processing and delivering the service, should therefore be more understandable if you realise it was a complete surprise.

(The surprise may or may not be quite as great as the exploding whale posted via Wired at the end of this post. Go on, you know you want to.)

Change is the only constant. How can we progress?

|

| The Change Curve based on the Kübler-Ross Grief model |

So, what happens now? How can the public move forward, to get to a position of trust and acceptance, that this is what is already happening with our hospital data (HES), and planned to happen with the majority of our GP stored data in future (whether we like the idea or not)?

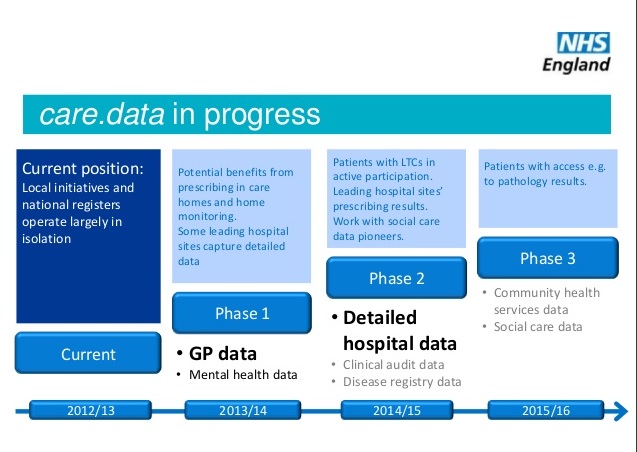

In order to move us along the curve, NHS England have a large task ahead. In fact, a series of tasks ahead, which are not going to happen overnight. How are change and communications working together?

As there’s no detailed ‘care.data progress’ public communications easy to see on the top level of NHS websites I can only see other info as it comes out through online search alerts. And since it’s my, my children’s and all of us as citizens, whose data that is being discussed here, I think we should be interested and want to find out and question the ongoing status. The GP FAQs have gone or are hard to find, and the patient FAQs are still inaccurate IMO. This page should be top level leading, not six unsearchable clicks down.

From the latest update in the care.data advisory group meeting notes, with much more concrete progress to see, it is good to see that communications features often, and note ‘a comprehensive engagement plan is already underway.’

That plan will be interesting to see mapped out as time goes on, but I do wonder whether it is the right time to be looking at engagement, when so much for the care.data programme remains to be clarified or is undecided?

Questions remain how less raw data can be given away, further legislation, the ‘one strike and out’ how to deal with data breaches, views on enabling small and medium enterprises (SMEs) data access, GP staff opt out understanding, public op out understanding, clarifying the narrative of risks and safeguards. Some steps to be reviewed not until ‘over the summer’. And that’s only a summary of a summary, I am sure only a glimpse of the foam on the top of the wave of what is being done under the surface.

An engagement plan can’t have gaps. Communications is not one-way, that’s PR. So we can only hope there is a real engagement underway of listening which will result in action, but not in ‘transmit mode’. Engagement needs to be concrete to work from day one. We don’t need a sticky plaster and pat on the head, we need fixes and facts to back them up.

Communications and Change

Why can comms not start now and be added to as we go along, you may ask? Whilst it can, and indeed most communications plans need some flexibility, a good Communications Plan needs to ride leashed tightly to the Change Management Plan. And given that different individuals are each somewhere different on the change curve, at any given point in time, you need to be able to address questions that any of them may have, simultaneously, regardless of whether they have just heard the news, or are almost finished their change journey. For GPs, their staff, other medical professionals, citizens and patients.

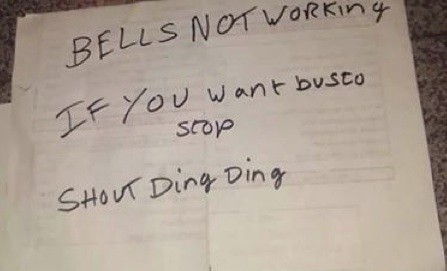

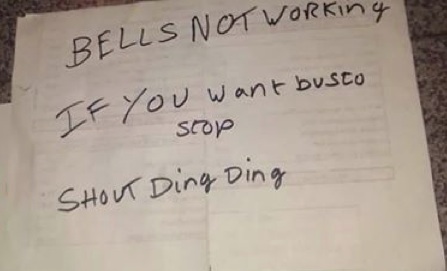

Riding the wave of the change curve, some are nearly back on the beach, when others haven’t yet entered the water. Some have got out and will not be persuaded back. Others may.

Therefore until many of the open issues are resolved, until governance and legislation is clear, unless it is focused on listening and resulting action, most communications can only be wasted PR rhetoric. Perhaps there are great plans. But Houston, we don’t have a communications problem. Honestly. As far as I can see.

There is no communications issue, there are issues which need communication.

Why? Because folks who opted out already will not be sold on the benefits. They will only be convinced by a clear picture of known and well governed, legislated, mitigated risks AND benefits. Then they can weigh up a decision. (Assuming indeed, the Secretary of State is a man of his word and maintains the patients’ right to object, which is not a legislative right.)

“The law is a statutory enactment which requires the disclosure of the data, which means the data becomes exempt from the main parts of the DPA.” (ICO)

For the population not reached yet, however, there is a requirement to at least give fair processing, even if you can debate the fineries, all common sense says make the same mistake twice, and you’re sunk.

The trickiest part in the communications, is to address different segments of the population who are at different points in the curve, at the same time. Some of whom are hard to reach.

I am sure there are many people working behind the scenes to bring about this managed change. Let’s not forget, this programme was intended first to launch a year ago. Professionals are working on this, it’s not new. But Dear God, please don’t launch more communications along the same lines as before. September saw GP materials go out with no training and no measure of how well practices had understood the materials. A misleading poster and misdelivered leaflet for patients created more confusion. Which all went out before proper governance, legislation and technical solutions were in place to make it all work well. The advisory group minutes and Mr.Kelsey’s letter indicate there is much work to be done in these areas still. Yet engagement activities are planned May-July.

To look at basics, I think these three things for starters, need resolved before you can talk about risk mediation:

1. a) Purposes of what data is taken and b) who accesses data: the care.data addendum which sought wider purposes and third party access by think-tanks and information intermediaries is still to resurface, after being returned by the GPES IAG in February for amendment. Which means final data users remain somewhat undefined. And we’re still pending the complete audit of past and current data recipients through the audit overseen by Sir Nick Partridge. [NB: since done in June < see post]

2. Amber is not Green – data protection: Why is potentially identifiable data and what really quite clearly, will be identifiable when so many companies sole purpose is to take a wide range of data sources and mash them together, given no data protection in law and no clear choice over its use in HES release?

It may for release from HSCIC be treated more carefully than green data only in so far as it is not publicly published on a website,and goes to committee review, but it may be provided to a wide range of commercial companies who then create information from it which they release.

The raw data’s nature can be sensitive to us and it’s certainly personal, so that we would expect it to be kept confidential, and yet it is shared and may be combined with recipient’s other data sets are at individual patient level? It feels like a great big whale in the room – it’s not green, we can’t protect it, but if we close our eyes it might go away.

It’s not conducive to trust, when it feels like a con. Just call me Ishmael.

3. Individual data control – opt out and rights: Point 2 leads to a huge potential iceberg ahead which still needs resolved. The UK and upcoming new EU protection laws and their, the ICO and the HSCIC definition of anonymous and pseudonymous data. We must understand how they are to apply and are not only legal, but feel just and fair to us as citizens. It should be looking ahead to meet the coming law now, shaping not avoiding best practices.

What rights does the individual have? How will GPs resolve their conflict of protecting patient confidentiality and complying with the new law requiring them to release it? Some GPs don’t think it’s a good idea.

There will be some citizens who want no data stored centrally at all and even want their HES back out. What will they say to someone who point blank does not want any of their medical record outside their practitioners’ control?

So, are we about to see a repeat of the same communications catastrophe – launching engagement, before we know what exactly what it is we’re talking about? Surely not. But looking at the calendar…

As an outsider, I just wonder how can effective engagement begin, when questions may be asked which cannot be answered?

Workshops to separate truth from myth, risk going down as well as Ahab in Melville’s story, if you have people who are upset, and you have nothing to offer them but unsupported ‘reassurance’. I’d like to see a webpage or presentation of those myths, because I don’t feel I’ve seen many myself. If anything, issues have been debunked by careful wording rather than straight talking.

Change and Trust

Change can’t be done to us without huge resistance. Change has to happen with us, if we are to trust and adopt it. If collectively we get stuck in anger and fear, we’ll not get to acceptance. And it actually has the potential, suggested Ben Goldacre, if not already done, to leave a negative wake on wider research & society.

There has to be trust in the change, that it is for widely acknowledged ‘right’ reasons.

There has to be trust that the terms of the change are defined and stable. Words such as currently, and initially, have little place in the definition of future agreements.

There has to be trust that what we will lose, is in proportion and outweighed by what we’ll gain from the new.

When we read global stories of how healthcare data is misused, and we can’t see who has access to our own data on any real-time rolling basis, it leaves open the fear that data can be given inappropriately, without check and balance, for months. The recently released register is one good thing to come from the debacle so far, and the further audits are ongoing, expected towards mid-May, but any future register is only going to be publicly accurate 4 times a year. It’s better than nothing, but surely not hard to update in real time.

Until the history is entirely transparent, it is a challenge to see how concerns about past use and lack of past governance, and the lack of trust those errors created will be possible to fix. The sensitivity of our raw data is likely only to increase as scope is broadened in future, and the scale of the requests is expected to increase as the era of Health Intelligence takes off and becomes ever more profitable for those third parties.

Trust will need to increase if anything proportionately, as this scale and sensitivity increases. So any communications of future releases and their governance needs to be sustained. It’s not an afterthought of ‘what we’ve done’. It’s the key to being allowed to carry on doing it.

Change Managers need to understand an individual’s own story, values and what makes them tick, to have an expectation of what the change impact (possibly negative) will be for individuals or groups and what’s in it for them (the positive) and any wider impacts, for example considering the Public Interest. And all leaders, need to have available from the start, the information which will answer the questions for people in each of these groups, at every stage of the curve.

Decisions in the public interest, may be subjective. Jeremy Hunt has said that we,

‘will “get through” the heated public debate this scheme has caused regarding patient privacy and the potential for the data to be re-identified.”

I’d like to hope we get more than ‘through it.’

To say that, underestimates the task ahead.

It’s not a tunnel or a final destination, but a process.

And the longer the data is shared over our lifetimes, the more likely it will be re-identified with all the other passive and other Big Data which is shared in our future. So there’s no patch, pop up and coast to the beach. I can only think this is a one time chance, and the leadership comments seem to underestimate it.

It must be done correctly now, to set up a framework which will be robust enough for the future size and complexity of the future Big Data vision.

Legislation to build a solid Future foundation

There are still many unknowns it reads from the meetings, from opt out, to wide ranging governance issues, to securing watertight legislation. The scale and sensitivity of the data and how it has been handled in the past, shows how the current model is not fit for purpose.

This week there is still crucial legislation being considered which will help to fundamentally cement or fail public trust.

Trust not only in how our data will be governed, but in common sense in our governing bodies. The legislation addresses:

- Retaining control and management of confidential information

- Putting the independent Information Governance Oversight panel on a statutory footing

- Independent oversight over certain directions and the accreditation scheme

etaining control and management of confidential information – See more at: http://www.allysonpollock.com/?p=1820#sthash.No8G7kcT.dpuf

retaining control and management of confidential information – See more at: http://www.allysonpollock.com/?p=1820#sthash.No8G7kcT.dpuf

I’m no legal beagle, but it appears to make excellent sense and the detailed wording (via Prof. Alison Pollock’s page) is very straightforward.

I hope it is clear that patient choice and public interest complement one another in these proposals. Just as Dr. Mark Taylor, Chair of CAG, outlined in an excellent essay,

“the current law of data protection, with its opposed concepts of ‘privacy’ and ‘public interest’, does not do enough to recognise the dependencies or promote the synergies between these concepts.”

If the Lords support Life Sciences’ interests, as many in the chamber do, they will need to support the proposals in order to ensure the public remain opted in to care.data.

Without these governance amendments, many more will opt out I am certain from talking to people on the street, and the value of the population-wide database will be undermined. So, the theory on paper next week, will have a crucial role in the practical outcome of the care.data implementation and its lifetime value.

No one said, change is easy

Importantly, in any theory one does well to remember the practical reality. Each response is unique to an individual. No one model will fit all. Each person commences the journey of a changing situation, from a different starting point. We each begin the process from a different level of baseline knowledge. We each have our own ways of dealing with loss, and experience different levels of anger or fear. There are early and late adopters.

Some things are difficult, but have to be gone through. For me, Tuesday was a day of looking back at wonderful memories.

We also sometimes need to accept what cannot be changed. When the time comes, I support the idea that we can live with a disease and dignity, not just the label that we are ‘dying’.

My final inspiration of the week, Kate Granger articulated this, so much better than I could, last week:

“I cannot imagine a human society free from cancer, no matter how much money we invest. As a cancer patient who will die in the relatively near future, I believe rather that instead of reaching for the traditional battle language, [life] is about living as well as possible, coping, acceptance, gentle positivity, setting short-term, achievable goals, and drawing on support from those closest to you.”

care.data requires courage from all the parties involved, because everyone is going through a certain process of change and compromise. Even those who planned the now delayed launch, need to recognise a need for change and why we’ve got to put a solid, not rushed foundation in now, and be in it for the long haul to get it right.

With lasting legislative powers, we public can better entrust our faith and data to the system, not just today, but into the future. With a proper independent Governance and oversight process we can hand you our trust for safekeeping with our records in good faith. We can only trust these proposed changes make not just waves, but make real progress.

If nothing really substantial changes in the pause, and we don’t see increased measures to create trust, all that will happen is a build up of frustration and pressure of all the people who can’t move forward from the initial anger and confusion. They will opt out. And there’s a risk public opinion will burst under pressure. No one will want to support health record sharing for any purposes, even bona fide good research, and there will be an explosion of opt outs. Projects will be abandoned, like a dead, washed up whale. (Which you really don’t want to happen. Really. It’s not pretty viewing, don’t say I didn’t warn you. But it’s kind of fascinating too and all the number crunching too.)

This can be avoided.

But plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Two months into the pause, are we seeing changes taking effect, or more of the same talk?

I look forward to better information on how and where our data has gone in the past. I think only after that will it be possible to get the history aired and resolved for improved future procedures once we have the complete audit picture, including that under Sir Nicholas Partridge, due towards the end of this month.

The further governance and independent oversight issues will be best resolved in legislation, which would help them be free of political change and create a framework worthy of the big data vision for the future.

In Summary

I hope the Change Management is as carefully thought out as communications and engagement is based on substantive steps before it.

These steps simply, start with:

1. a) Tighten and define clearly the purposes of what data is taken and b) who accesses data. Now and for future change.

2. Amber is not Green – data protection: Tighten what is potentially identifiable data and what really quite clearly, will be identifiable when so many companies sole purpose is to take a wide range of data sources and mash them together.

3. Individual data control – opt out, and legal rights. Will opt out get a statutory footing rather than Mr.Hunt’s word? Will we design now, for change in the UK and upcoming new EU protection laws?

Tighten the processes, define more of the facts, so you know what you’re communicating. Let people ask questions, and let us have sufficient time to go through the curve.

A rushed rollout, will create more people who block the change, opt out, and never return.

I realise much of this post addresses how I feel, and the feelings I have picked up from care.data events, from others discussing it on the street and school playground. Emotions have a role to play in this discussion, but better facts will go a long way to making objective informed decisions. And crucially, our decision making must be allowed to be objective and free from emotional coercion.

I’m cautiously optimistic and look forward to seeing public materials to get the GP profession and public on board and riding the care.data change curve each at their own pace. There is clearly a tonne of work to be done. It’s not going to be glassy, by any stretch of the imagination, but perhaps we need a few rough times to remind us what matters most to us, and why.

It makes us engage.

The question is, in the coming weeks and months, is NHS England prepared for genuine change and engagement with the public, not just PR?

![Thoughts on Digital Participation and Health Literacy: Opportunities for engaging citizens in the NHS [#NHSWDP 1]](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/FullSizeRender-640x372.jpg)

![Launching genomics, lifeboats, & care.data [part 2]](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/rosetta_image-672x372.jpg)