Let’s assume the question of public trust is as important to those behind data sharing plans in the NHS [1] as they say it is. That the success of the care.data programme today and as a result, the very future of the NHS depends upon it.

“Without the care.data programme, the health service will not have a future, said Tim Kelsey, national director for patients and information, NHS England.” [12]

And let’s assume we accept that public trust is not about the public, but about the organisation being trustworthy.[2]

The next step is to ask, how trustworthy is the programme and organisation behind care.data? And where and how do they start to build?

The table discussion on [3] “Building Public Trust in Data Sharing” considered “what is the current situation?” and “why?”

What’s the current situation? On trust public opinion is measurable. The Royal Statistical Society Data Trust Deficit shows that the starting points are low with the state and government, but higher for GPs. It is therefore important that the medical profession themselves trust the programme in principle and practice. They are after all the care.data point of contact for patients.

The current status on the rollout, according to news reports, is that pathfinder practices are preparing to rollout [4] communications in the next few weeks. Engagement is reportedly being undertaken ‘over the summer months’.

Understanding both public trust and the current starting point matters as the rollout is moving forwards and as leading charity and research organisation experts said: “Above all, patients, public and healthcare professionals must understand and trust the system. Building that trust is fundamental. We believe information from patient records has huge potential to save and improve lives but privacy concerns must be taken seriously. The stakes are too high to risk any further mistakes.” [The Guardian Letters, July 27, 2015]

Here’s three steps I feel could be addressed in the short term, to start to demonstrate why the public and professionals should trust both organisation and process.

What is missing?

1. Opt out: The type 2 opt out does not work. [5]

2 a. Professional voices called for answers and change: As mentioned in my previous summary various bodies called for change. Including the BMA whose policy [6] remains that care.data should be on a patient opt-in basis.

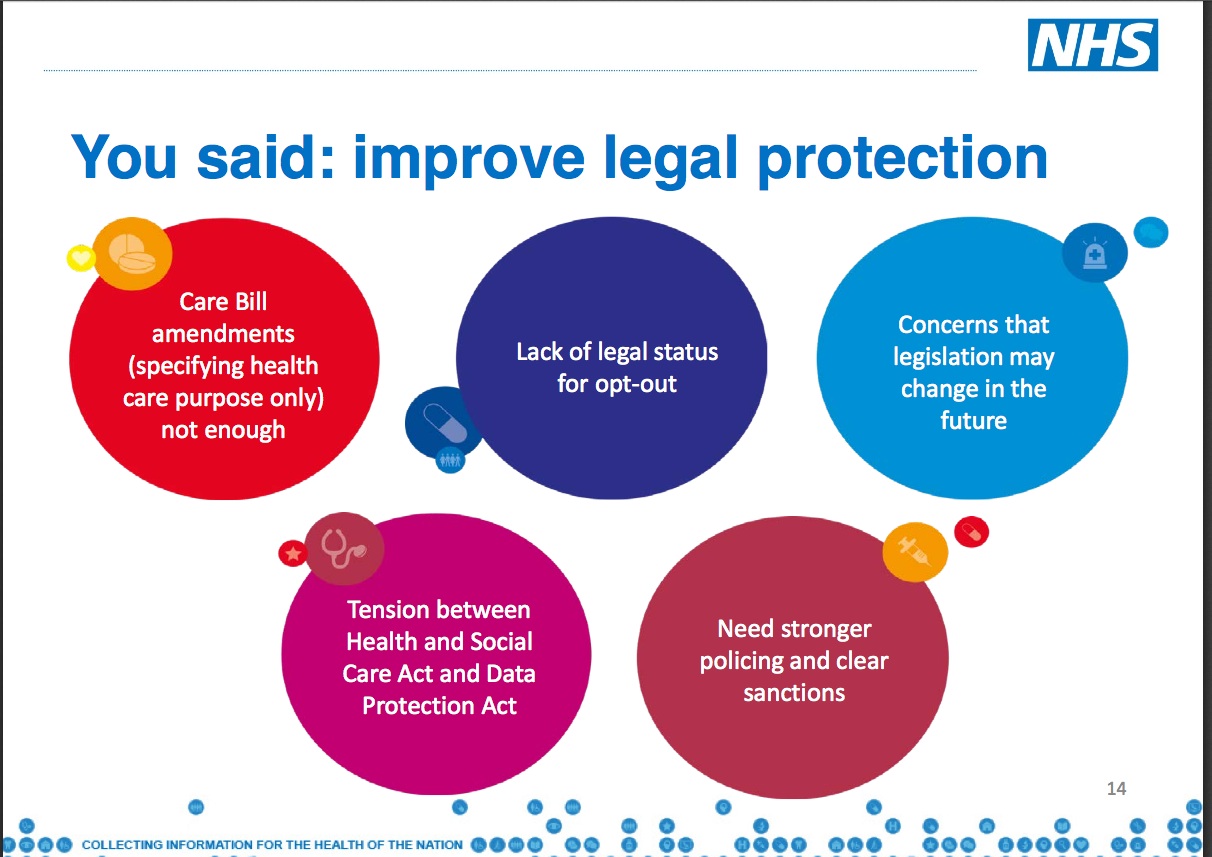

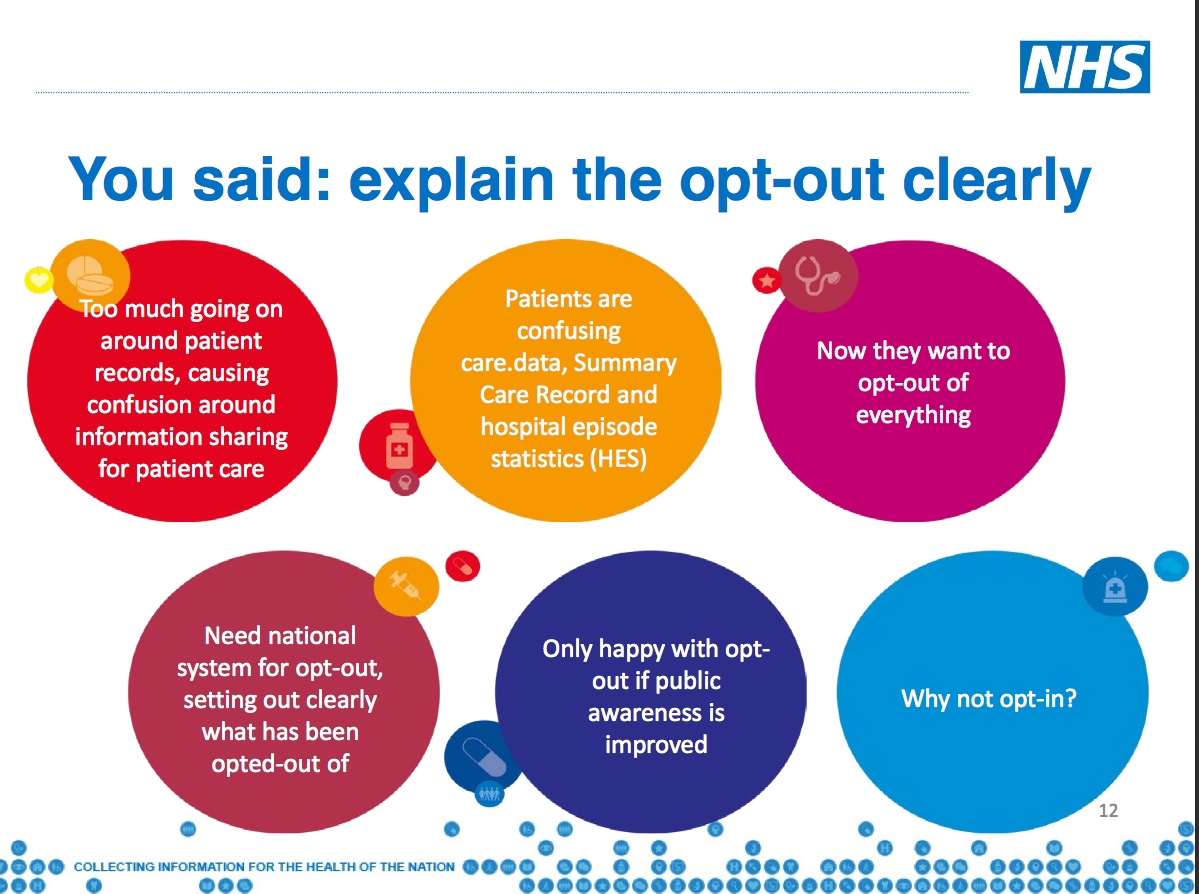

2b. Public voices called for answers and change: care.data’s own listening event feedback [7] concluded there was much more than ‘communicate the benefits’ that needed done. There is much missing. Such as questions on confusing SCR and care.data, legislation and concern over controlling its future change, GP concerns of their ethical stance, the Data Guardian’s statutory footing, correction of mistakes, future funding and more.

How are open questions being addressed? If at all?

3. A single clear point of ownership on data sharing and public trust communications> Is this now NIB, NHS England Patients and Information Directorate, the DH who owns care.data now? It’s hard to ask questions if you don’t know where to go and the boards seem to have stopped any public communications. Why? The public needs clarity of organisational oversight.

What’s the Solution?

1. Opt out: The type 2 opt out does not work. See the post graphic, the public wanted more clarity over opt out in 2014, so this needs explained clearly >>Solution: follows below from a detailed conversation with Mr. Kelsey.

2. Answers to professional opinions: The Caldicott panel, raised 27 questions in areas of concern in their report. [8] There has not yet been any response to address them made available in the public domain by NHS England. Ditto APPG report, BMA LMC vote, and others >> Solution: publish the responses to these concerns and demonstrate what actions are being done to address them.

2b. Fill in the lack of transparency: There is no visibility of any care.data programme board meeting minutes or materials from 2015. In eight months, nothing has been published. Their 2014 proposal for transparency, appears to have come to nothing. Why? The minutes from June-October 2014 are also missing entirely and the October-December 2014 materials published were heavily redacted. There is a care.data advisory board, which seems to have had little public visibility recently either. >> Solution: the care.data programme business case must be detailed and open to debate in the public domain by professionals and public. Scrutiny of its associated current costs and time requirements, and ongoing future financial implications at all levels should be welcomed by national, regional (CCG) and local level providers (GPs). Proactively publishing creates demonstrable reasons why both the organisation, and the plans are both trustworthy. Refusing this without clear justifications, seems counter productive, which is why I have challenged this in the public interest. [10]

3. Address public and professional confusion of ownership: Since data sharing and public trust are two key components of the care.data programme, it seems to come under the NIB umbrella, but there is a care.data programme board [9] of its own with a care.data Senior Responsible Owner and Programme Director. >> Solution: an overview of where all the different nationally driven NHS initiatives fit together and their owners would be helpful.

[Anyone got an interactive Gantt chart for all national level driven NHS initiatives?]

This would also help public and professionals see how and why different initiatives have co-dependencies. This could also be a tool to reduce the ‘them and us’ mentality. Also useful for modelling what if scenarios and reality checks on 5YFV roadmaps for example, if care.data pushes back six months, what else is delayed?

If the public can understand how things fit together it is more likely to invite questions, and an engaged public is more likely to be a supportive public. Criticism can be quashed if it’s incorrect. If it is justified criticism, then act on it.

Yes, these are hard decisions. Yes, to delay again would be awkward. If it were the right decision, would it be worse to ignore it and carry on regardless? Yes.

The most important of the three steps in detail: a conversation with Mr. Kelsey on Type 2 opt out. What’s the Solution?

We’re told “it’s complicated.” I’d say “it’s simple.” Here’s why.

At the table of about fifteen participants at the Bristol NIB event, Mr. Kelsey spoke very candidly and in detail about consent and the opt out.

On the differences between consent in direct care and other uses he first explained the assumption in direct care. Doctors and nurses are allowed to assume that you are happy to have your data shared, without asking you specifically. But he said, “beyond that boundary, for any other purpose, that is not a medical purpose in law, they have to ask you first.”

He went on to explain that what’s changed the whole dynamic of the conversation, is the fact that the current Secretary of State, decided that when your data is being shared for purposes other than your direct care, you not only have the right to be asked, but actually if you said you didn’t want it to be shared, that decision has to be respected, by your clinician.

He said: “So one of the reasons we’re in this rather complex situation now, is because if it’s for analysis, not only should you be asked, but also when you say no, it means no.”

Therefore, I asked him where the public stands with that now. Because at the moment there are ca. 700,000 people who we know said no in spring 2014.

Simply: They opted out of data used for secondary purposes, and HSCIC continues to share their data.

“Is anything more fundamentally damaging to trust, than feeling lied to?”

Mr. Kelsey told the table there is a future solution, but asked us not to tweet when. I’m not sure why, it was mid conversation and I didn’t want to interrupt:

“we haven’t yet been able to respect that preference, because technically the Information Centre doesn’t have the digital capability to actually respect it.”

He went on to say that they have hundreds of different databases and at the moment, it takes 24 hrs for a single person’s opt out to be respected across all those hundreds of databases. He explained a person manually has to enter a field on each database, to say a person’s opted out. He asked the hoped-for timing not be tweeted but explained that all those current historic objections which have been registered will be respected at a future date.

One of the other attendees expressed surprise that GP practices hadn’t been informed of that, having gathered consent choices in 2014 and suggested the dissent code could be extracted now.

The table discussion then took a different turn with other attendee questions, so I’m going to ask here what I would have asked next in response to his statement, “if it’s for analysis, not only should you be asked, but also when you say no, it means no.”

Where is the logic to proceed with pathfinder communications?

What was said has not been done and you therefore appear untrustworthy.

If there will be a future solution it will need communicated (again)?

“Trust is not about the public. Public trust is about the organisation being trustworthy.”

There needs to be demonstrable action that what the org said it would do, the org did. Respecting patient choice is not an optional extra. It is central in all current communications. It must therefore be genuine.

Knowing that what was promised was not respected, might mean millions of people choose to opt out who would not otherwise do so if the process worked when you communicate it.

Before then any public communications in Blackburn and Darwen, and Somerset, Hampshire and Leeds surely doesn’t make sense.

Either the pathfinders will test the same communications that are to be rolled out as a test for a national rollout, or they will not. Either those communications will explain the secondary uses opt out, or they will not. Either they will explain the opt out as is [type 2 not working] or as they hope it might be in future. [will be working] Not all of these can be true.

People who opt out on the basis of a broken process simply due to a technical flaw, are unlikely to ever opt back in again. If it works to starts with, they might choose to stay in.

Or will the communications roll out in pathfinders with a forward looking promise, repeating what was promised but has not yet been done? We will respect your promise (and this time we really mean it)? Would public trust survive that level of uncertainty? In my opinion, I don’t think so.

There needs to be demonstrable action in future as well, that what the org said it would do, the org did. So the use audit report and how any future changes will be communicated both seem basic principles to clarify for the current rollout as well.

So what’s missing and what’s the solution on opt out?

We’re told “it’s complicated.” I say “it’s simple.” The promised opt out must work before moving forward with anything else. If I’m wrong, then let’s get the communications materials out for broad review to see how they accommodate this and the future re-communication of second process.

There must be a budgeted and planned future change communication process.

So how trustworthy is the programme and organisation behind care.data?

Public opinion on trust levels is measurable. The Royal Statistical Society Data Trust Deficit shows that the starting points are clear. The current position must address the opt out issue before anything else. Don’t say one thing, and do another.

To score more highly on the ‘truthworthy scale’ there must be demonstrable action, not simply more communications.

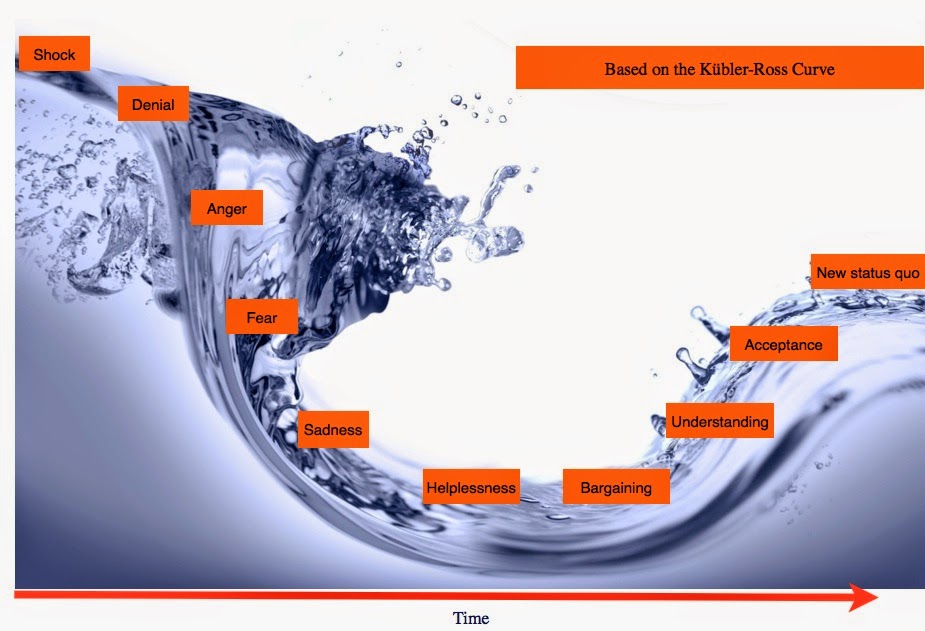

Behaviours need change and modelled in practice, to focus on people, not tools and tech solutions, which make patients feel as if they are less important to the organisations than their desire to ‘enable data sharing’.

Actions need to demonstrate they are ethical and robust for a 21stC solution.

Policies, practical steps and behaviours all play vital roles in demonstrating that the organisations and people behind care.data are trustworthy.

These three suggestions are short term, by that I mean six months. Beyond that further steps need to be taken to be demonstrably trustworthy in the longer term and on an ongoing basis.

Right now, do I trust that the physical security of HSCIC is robust? Yes.

Do I trust that the policies in the programme would not to pass my data in the future to third party commercial pharma companies? No.

Do I believe that for enabling commissioning my fully identifiable confidential health records should be stored indefinitely with a third party? No.

Do I trust that the programme would not potentially pass my data to non-health organisations, such as police or Home Office? No.

Do I trust that the programme to tell me if they potentially change the purposes from those which they outline now ? No.

I am open to being convinced.

*****

What is missing from any communications to date and looks unlikely to be included in the current round and why that matters I address in my next post Building Public Trust [4]: Communicate the Benefits won’t work for care.data and then why a future change management model of consent needs approached now, and not after the pilot, I wrap up in [5]: Future solutions.

![Building Public Trust in care.data datasharing [3]: three steps to begin to build trust](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/optout_ppt-672x372.jpg)

![Building Public Trust [2]: a detailed approach to understanding Public Trust in data sharing](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Trust-e1426443553441-672x372.jpg)

![Building Public Trust in care.data sharing [1]: Seven step summary to a new approach](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/edison1-672x372.jpg)