“EdTech UK will be a pro-active organisation building and accelerating a vibrant education and learning technology sector and leading new developments with our founding partners. It will also be a front door to government, educators, companies and investors from Britain and globally.”

Ian Fordham, CEO, EdTech UK

This front door is a gateway to access our children’s personal data and through it some companies are coming into our schools and homes and taking our data without asking. And with that, our children lose control over their safeguarded digital identity. Forever.

Companies are all “committed to customer privacy” in those privacy policies which exist at all. However, typically this means they also share your information with ‘our affiliates, our licensors, our agents, our distributors and our suppliers’ and their circles are wide and often in perpetuity. Many simply don’t have a published policy.

Where do they store any data produced in the web session? Who may access it and use it for what purposes? Or how may they use the personal data associated with staff signing up with payment details?

According to research from London & Partners, championed by Boris Johnson, Martha Lane-Fox and others in EdTech, education is one of the fastest growing tech sectors in Britain and is worth £45bn globally; a number set to reach a staggering £129bn by 2020. And perhaps the EdTech diagrams in US dollars shows where the UK plan to draw companies from. If you build it, they will come.

The enthusiasm that some US EdTech type entrepreneurs I have met or listened to speak, is akin to religious fervour. Such is their drive for tech however, that they appear to forget that education is all about the child. Individual children. Not cohorts, or workforces. And even when they do it can be sincerely said, but lacks substance when you examine policies in practice.

How is the DfE measuring the cost and benefit of tech and its applications in education?

Is anyone willing to say not all tech is good tech, not every application is a wise application? Because every child is unique, not every app is one size fits all?

My 7-yo got so caught up in the game and in the mastery of the app their class was prescribed for homework in the past, that she couldn’t master the maths and harmed her confidence. (Imagine something like this, clicking on the two correct sheep with numbers stamped on them, that together add up to 12, for example, before they fall off and die.)

She has no problem with maths. Nor doing sums under pressure. She told me happily today she’d come joint second in a speed tables test. That particular app style simply doesn’t suit her.

I wonder if other children and parents find the same and if so, how would we know if these apps do more harm than good?

Nearly 300,000 young people in Britain have an anxiety disorder according to the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Feeling watched all the time on-and offline is unlikely to make anxiety any better.

How can the public and parents know that edTech which comes into the home with their children, is behaviourally sound?

How can the public and parents know that edTech which affects their children, is ethically sound in both security and application?

Where is the measured realism in the providers’ and policy makers fervour when both seek to marketise edTech and our personal data for the good of the economy, and ‘in the public interest’.

Just because we can, does not always mean we should. Simply because data linkage is feasible, even if it brings public benefit, cannot point blank mean it will always be in our best interest.

In whose best Interest is it anyway?

Right now, I’m not convinced that the digital policies at the heart of the Department for Education, the EdTech drivers or many providers have our children’s best interests at heart at all. It’s all about the economy; when talking if at all about children using the technology, many talk only of ‘preparing the workforce’.

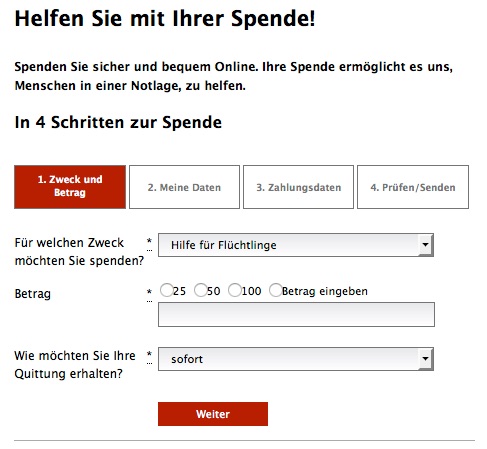

Are children and parents asked to consent at individual level to the terms and conditions of the company and told what data will be extracted from the school systems about their child? Or do schools simply sign up their children and parents en masse, seeing it as part of their homework management system?

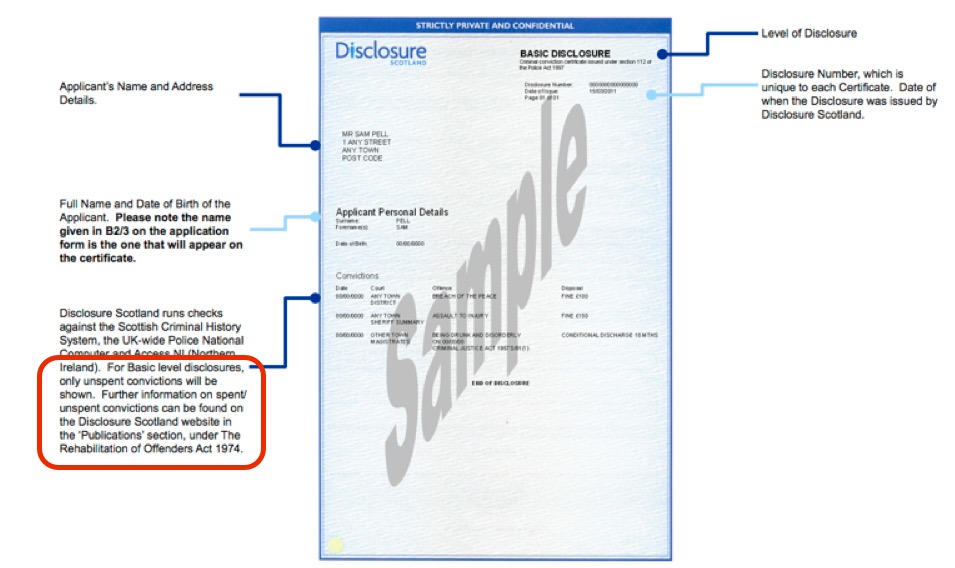

How much ‘real’ personal data they use varies. Some use only pseudo-IDs assigned by the teacher. Others log, store and share everything they do assigned to their ID or real email address , store performance over time and provide personalised reports of results.

Teachers and schools have a vital role to play in understanding data ethics and privacy to get this right and speaking to many, it doesn’t seem something they feel well equipped to do. Parents aren’t always asked. But should schools not always have to ask before giving data to a commercial third party or when not in an ’emergency’ situation?

I love tech. My children love making lego robots move with code. Or driving drones with bananas. Or animation. Technology offers opportunity for application in and outside schools for children that are fascinating, and worthy, and of benefit.

If however all parents are to protect children’s digital identity for future, and to be able to hand over any control and integrity over their personal data to them as adults, we must better accommodate children’s data privacy in this 2016 gold rush for EdTech.

Pupils and parents need to be assured their software is both educationally and ethically sound. Who defines those standards?

Who is in charge of Driving, Miss Morgan?

Microsoft’s vice-president of worldwide education, recently opened the BETT exhibition and praised teachers for using technology to achieve amazing things in the classroom, and urged innovators to “join hands as a global community in driving this change”.

While there is a case to say no exposure to technology in today’s teaching would be neglectful, there is a stronger duty to ensure exposure to technology is positive and inclusive, not harmful.

Who regulates that?

We are on the edge of an explosion of tech and children’s personal data ‘sharing’ with third parties in education.

Where is its oversight?

The community of parents and children are at real risk of being completely left out these decisions, and exploited.

The upcoming “safeguarding” policies online are a joke if the DfE tells us loudly to safeguard children’s identity out front, and quietly gives their personal data away for cash round the back.

The front door to our children’s data “for government, educators, companies and investors from Britain and globally” is wide open.

Behind the scenes in pupil data privacy, it’s a bit of a mess. And these policy makers and providers forgot to ask first, if they could come in.

If we build it, would you come?

My question now is, if we could build something better on pupil data privacy AND better data use, what would it look like?

Could we build an assessment model of the collection, use and release of data in schools that could benefit pupils and parents, AND educational establishments and providers?

This could be a step towards future-proofing public trust which will be vital for companies who want a foot-in-the door of EdTech. Design an ethical framework for digital decision making and a practical data model for use in Education.

Educationally and ethically sound.

If together providers, policy makers, schools at group Trust level, could meet with Data Protection and Privacy civil society experts to shape a tool kit of how to assess privacy impact, to ensure safeguarding and freedoms, enable safe data flow and help design cybersecurity that works for them and protects children’s privacy that is lacking today, designing for tomorrow, would you come?

Which door will we choose?

*******

image credit: @ Ben Buschfeld Wikipedia

*added February 13th: Oftsed Chair sought from US