As European leaders meet for the sixth time this year to talk about what to do about refugees, people on the ground are getting stuff done.

Freilassing Hilft, a collaboration of volunteers founded through four friends and a Facebook group eight weeks ago, feeds 1500 different people every day, who pass through the small border town in Germany.

“We’re expecting another 700 more this evening,” Rolf said, volunteering with the separate and long-established charity Caritas at Salzburg’s main station on the other side of the border.

Two “special” trains arrive daily from the south, from Vienna.

Individual men, women and children have become a package – ‘ die Flüchtlinge‘ – refugees – who arrive en masse. From the platforms they are escorted by police and young military service soldiers to segregated areas in the fluorescent lit station concourse.

There they wait. Standing in an orderly narrow queue between cold aluminum crowd control barriers near the exit at the back of the station.

Chatting and relaxed at both ends of the line, a dozen heavily armed police supervise passing these people on. Dark navy uniforms stand out against the reflective white flooring. Big boots and bigger guns don’t seem a very friendly way to greet up to 1500 people a day who have left behind violence and conflict, with only the possessions they can carry; each with a small rucksack, some with small children. The children look as mine would after travelling; a little fraught, bewildered and awake in harsh neon at night, when they should be asleep. Most but not all, clinging to a trusted parent. And no crying.

One teen is wandering on her own, looking a little lost, drowning in a turquoise terry towelling dressing gown that’s too big. I wonder what her story is.

Along the ‘safety’ barricade, white vested volunteers weave back and forth holding out plastic bags of cheese sandwiches and drinks. “Hold them up high,” says Rolf waving 500ml water bottles in the air in his blue, disposable-gloved hands. “If they want them they’ll reach out and take them, you don’t need to say anything.”

There is calm and quiet. There are no words. Tense and tired looking faces nod respectfully to volunteers in appreciation of support. And still they wait for the special buses laid on to bring them across the Austrian-German border, to the small town of Freilassing, seven kilometres away. They will soon be in Germany.

Refugees can only cross the border on these supervised buses. Refugees aren’t allowed on the regular trains from Salzburg any more at all.

Special buses get driven discretely between Salzburg and Freilassing, often in the dark. The town of 16,000 inhabitants has been the checkpoint entry for numbers equivalent to about a tenth of its own population every day since the end of August.

From Freilassing special trains are onwardly coordinated by the Bundesbahn to take the refugees to a scattering of cities across the country. The refugees don’t get told where they are going. That’s deliberate, said local volunteer, eighteen year-old Jana on the platform in Germany the next morning. She’s the deputy leader of the volunteer group Freilassing Hilft, an organisation founded through four friends’ collaboration in a Facebook group just 8 weeks ago, to give refugees support in transit.

“Some people have specific places they want to reach”, she explained. “They may have family members who they know are in Hamburg for example, and only want to get sent there. It could be upsetting to find they’re being sent somewhere else.”

Berlin, Magdeburg, they’ve been widely distributed, but few helpers know exactly where either.

While most refugees transfer directly from the Austrian buses to German train after registration checks and getting lunch bags from local volunteers, if a train isn’t due straight away they are bussed less than mile away to the Sägewerkstraße centre where they will stay no longer than 24 hours.

Those people who have not yet been registered by police – under tarpaulin awnings on the station platform, or on the bridge the Saarlachbrucke crossing point thirty at a time – go through the registration process at the centre.

In the dry and protected space the men, women and children get some respite, from the weather at least. Donations of winter clothes and shoes are distributed by Caritas volunteers and Freilassing Hilft to those who need them. Medics and professional volunteers can care for health needs. So close to their destination, it can be tense.

Sixty-four year old Kunnikunde joined the Caritas volunteer group in October. A group staffed mainly by pensioners since the students have returned to their studies. She helps distribute the donated clothing inside the former furniture showroom. “Helping them, seeing them smile, afterwards when it is over it is a great feeling, like running a marathon”, she said.

It’s not the same for everyone who works inside though. For the professionals who have been helping for longer, this intensive support is taking its toll. “I see dark faces in my dreams,” one told me. “I can’t forget them.” He sighed, clapped me on the shoulder, as if giving me some sign of solidarity in spirit. I wondered what support he needs and feels able to take, as he gives to others. He pulled on blue plastic gloves each with a professional snap, and went back inside.

The vast building is shut to other outsiders. It has no windows. Security teams patrol the barrier lines, marked off with tape and supported by local police. Whether it’s more to keep people from getting out or others getting in, I’m not sure.

It is not overstatement to say this is the biggest humanitarian disaster Europe has seen since the Second World War and Germany seventy years on, is again redistributing people fleeing war and its effects. As a border town, people in Freilassing have had plenty of experience.

Local feeling is mixed, says Jana. “We have three shifts,” she explained. “All together in the last five weeks we had probably 450 volunteers come and help us. And we get on well with the other organisations. We all work well together, the relationship with the police is very pleasant. But we certainly need to watch that the [public] mood doesn’t change.”

Since I met her two weeks ago, that number has rocketed to over two thousand individuals helping out, some coming to help from miles away.

Their organised management of community spirit is exemplary. They’ve channelled local people wanting to help, into actual donations and distribution of food and drink. An empty concrete floored shell of a shop-under-renovation is their base opposite the station to accept regular donations of thousands of apples, bananas, cereal bars, water, and sandwiches. Volunteers take shifts in the unheated room and bag up packed lunches for distribution to refugees arriving off the buses. The group has borrowed a handful of supermarket trolleys to take supplies across the road.

Today’s “wish list” on Facebook:

– men’s winter shoes sizes 6+

– Bananas

– White rolls

– Still mineral water 0,5l

– children’s drinks 0,2l

– drawing things

– Babyshoes sizes 19-22

– Baby milk and bottles

“This shift is simply packing the lunch bags for a couple of hours, and we get lots of people if we put out a call,” Jana explained when I asked how they get hold of what they need. “We can say, we need bananas, and after two hours we have sixteen crates of fruit and then people come along saying, but you have loads, you’re hoarding it. Other times we have nothing and need to use cash donations to buy everything ourselves. Last week we had to go twice a day to the supermarket, but we can’t go to Aldi anymore and just buy up all their stock. We need to pre-order and what we need can change in a matter of minutes. It’s hard to plan with.”

It’s an impressive set up by students who decided they could not simply stand by and do nothing. As we chat two more volunteers come along to register for shifts and Margret, a local mother of three, drops in a huge crate of apples from her orchard.

“What else can we do?” she asks. “You can’t just leave these people with nothing. Unless they felt forced to, they wouldn’t leave. There are families, and young children who are scared, and alone, and they need our help.”

One recent good news story Jana told me, had everyone in tears.

The police helped an asylum seeking Syrian husband in the north of Germany to go south again and reach Freilassing when he heard his wife had managed to escape the war zone one year after he had. Police had escorted him to the Sägewerkstraße, the building now known by the name of its street; enormous open plan furniture warehouse space donated by a local landowner as a staging post for the refugees’ journey. Meeting his wife after a year and two tortuous journeys apart was an emotional experience for them both, as well as all the Caritas charity and Red Cross staff involved. The asylum seeking couple were able to leave together and returned to his new home in the north. A rare good news story. Not all refugees find family or complete the journey safely with family they set out with. Not all refugees are from Syria, and some have traveled for up to two years before this last step to what they hope will be safety.

At the Austrian-German border police now check the ordinary vehicles passing through and ask for papers, a return of the border controls that had been removed in the Schengen agreement. A recent change which taxi driver Andreas is starting to feel has become too much of a burden on residents.

“For our children, or our children’s children, what is the future going to look like? We’ve got our own problems. Poverty, housing the elderly, and there never seems to be money to fix it. But suddenly for refugees, the money’s there.”

That Saturday saw two demonstrations.

One crowd called for support of the border towns, such as Freilassing, just as for the organisations and supporters who are engaging themselves in the work with the refugees. The Caritas Director Pralat Hans Lindenberger said that the refugees also needed to be shared fairly across the German states, as quickly and fairly as possible.

In the counter demonstration many of the attendees were brought in from different parts of Germany, says Jana, with few locals from far right and recognised Nazi organisations.

Supporters are however still signing up to help. While the number of refugees seeking asylum usually falls in winter as seas become more dangerous, this shows no sign of change yet despite or because of the reportedly cut rate crossings offered by the human traffickers.

Others are getting involved to help but to the volunteers it seems ad hoc. This Telekom portal launched today offering multi-lingual support. Long term volunteers will welcome the support tools for the refugees and their own staff.

Helpers and organisations are all calling for central government support.

In the short term, as winter snows may arrive soon, broader cooperation of nation states at government level in funding and manpower is needed in a consistent collaborative approach, as embodied by the Freilassing organisations in the microcosm of the Austrian-German border.

“Basically”, says the Red Cross volunteer, “all our leaders need to lead. Not only ours.”

Everyone is calling for greater leadership from not only the German government and more from Austria, but a collaboration including the UK. When I said I’m from the UK, they laughed. Since Germany takes the same number a day in this small town, as we might in two months time, I’m not surprised.

Austrian ‘support’ is also felt to be cursory, simply passing people on to Germany. No one knows how long goodwill in Freilassing can last. But volunteer numbers still say, ‘refugees welcome.’

Winter has begun. Although more support has been announced it is as yet unclear to the volunteers what it will offer where.

Unless there is safe passage to travel, and shelter at the point of arrival and all along ‘the route of Hope’ from Greece to Germany, the volunteers in Freilassing won’t help as many people as they do today, including the hundreds of unaccompanied children.

In the Alpine cold, many of them will simply never reach the border at all.

This UK response is not enough, not in this Parliament or even next year.

As political leaders prepare to meet in Malta to discuss measures to stem the flow of migrants and refugees from Africa to Europe, I think of Rolf’s words, “you don’t need to say anything.” But we do.

We need to speak up, so they hear a million voices of migrants. Speak up so that our leaders know they have the support of many people who want a more positive proactive approach in our population, but are not as vocal as the anti-immigration crowds. Speak up for the children who are still to set sail.

Any further border control agreements must put respect for human rights at their heart, not put more barriers in the way of people migrating or those getting on with grassroots practical support. Leaders must enable refugee routes to safety, and condemn those placing these people in more harm.

These people are survivors. They have not walked there, seen loved ones drown, given up all they know, for the joy of voluntourism. People in Germany laughed at our government’s commitment to take our share of people. It’s the only laugh I’ve heard recently in relation to refugee support.

As Kunnikunde said,“We have big hearts, but our generosity cannot go on forever. We all need to do this together.”

*****

*****

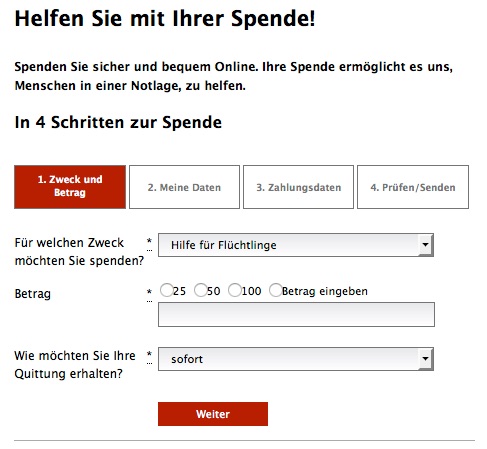

If you want to help make a difference and support refugees through volunteers at the organisation Freilassing Hilft (Freilassing Helps) you can make a regular or one-off donation. This enables them to buy stock according to need and in line with what donors have already provided.

Donations care of the charity:

Verein Europäischer Zwillings- und Mehrlingsfamilien e. V.

Account: VR RB Oberbayern Südost

IBAN: DE 787 109 000 000 002 310 45

BIC: GENODEF1BGL

Purpose: “FreilassingHilft”

The purpose is important so that “FreilassingHilft” gets the donation.

For a receipt of your donation, email: das-kontakt@freilassing.de. More information: see their Facebook group.

OR consider the Red Cross or the long established local Caritas.

Thank you.

Foto credit and story supported by Freilassing Hilft