The CDEI has published ‘new analysis on the use of data in local government during the COVID-19 crisis’ (the Report) and it features some similarities in discussing data that the Office for AI roadmap (the Roadmap) did in January on machine learning.

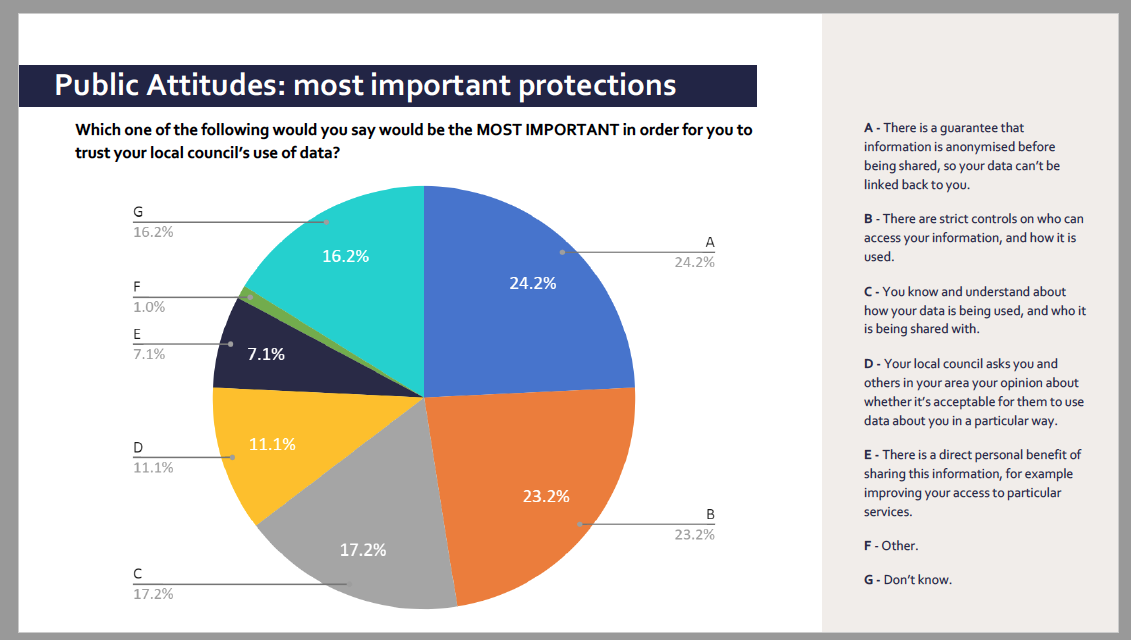

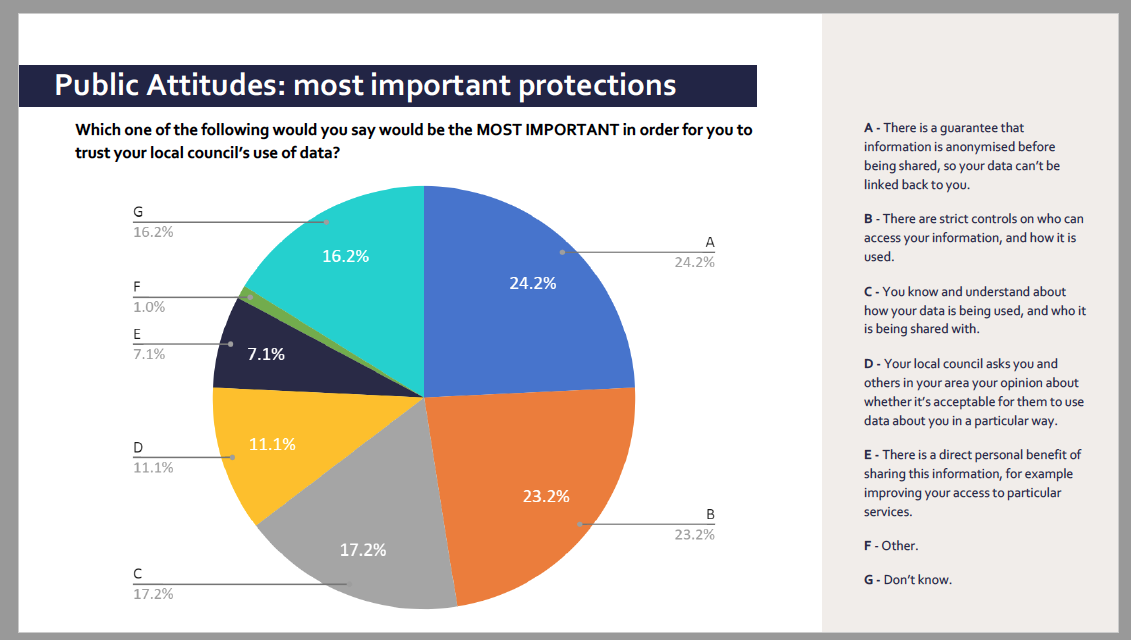

A notable feature is that the CDEI work includes a public poll. Nearly a quarter of 2,000 adults said that the most important thing for them, to trust the council’s use of data, would be “a guarantee that information is anonymised before being shared, so your data can’t be linked back to you.”

Both the Report and the Roadmap shy away from or avoid that problematic gap in their conclusions, between public expectations and reality in the application of data used at scale in public service provision, especially in identifying vulnerability and risk prediction.

Both seek to provide vision and aims around the future development of data governance in the UK.

The fact is that everyone must take off their rose-tinted spectacles on data governance to accept this gap, and get basics fixed in existing practice to address it. In fact, as academic Michael Veale wrote, often the public sector is looking for the wrong solution entirely. “The focus should be on taking off the ‘tech goggles’ to identify problems, challenges and needs, and to not be afraid to discover that other policy options are superior to a technology investment.”

But used as it is, the public sector procurement and use of big data at scale, whether in AI and Machine Learning or other systems, require significant changes in approach.

The CDEI poll asked, If an organisation is using an algorithmic tool to make decisions, what do you think are the most important safeguards that they should put in place 68% rated, that humans have a key role in overseeing the decision-making process, for example reviewing automated decisions and making the final decision, in their top three safeguards.

So what is this post about? Why our arms length bodies and various organisations’ work on data strategy are hindering the attainment of the goals they claim to promote, and what needs fixed to get back on track. Accountability.

Framing the future governance of data

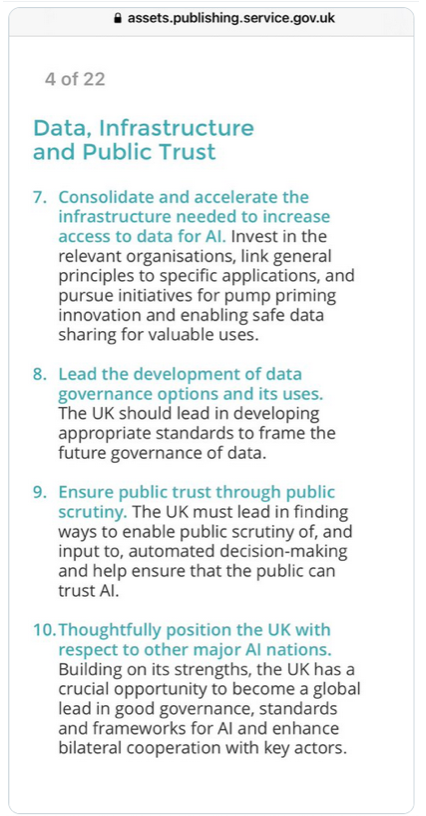

On Data Infrastructure and Public Trust, the AI Council Roadmap stated an ambition to, “Lead the development of data governance options and its uses. The UK should lead in developing appropriate standards to frame the future governance of data.”

To suggest we not only should be a world leader but imagine that there is the capability to do so, suggests a disconnect with current reality, none of which was mentioned in the Roadmap but is drawn out a little more in the CDEI Report from local authority workshops.

When it comes to data policy and Artificial Intelligence (AI) or Machine Learning (ML) based on data processing and therefore dependent on its infrastructure, suggesting we should lead on data governance, as if separate from the existing standards and frameworks set out in law, would be disastrous for the UK and businesses in it. Exports need to meet standards in the receiving countries. You cannot just ‘choose your own’ adventure here.

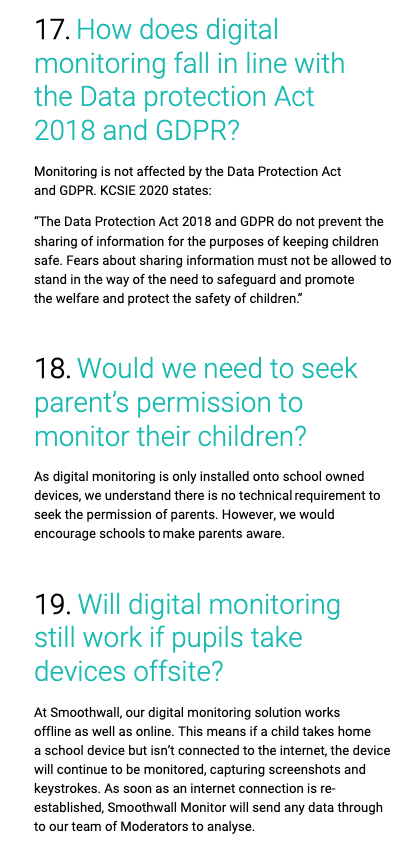

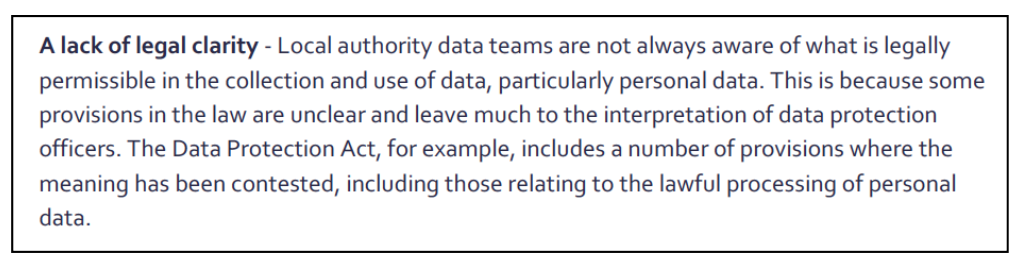

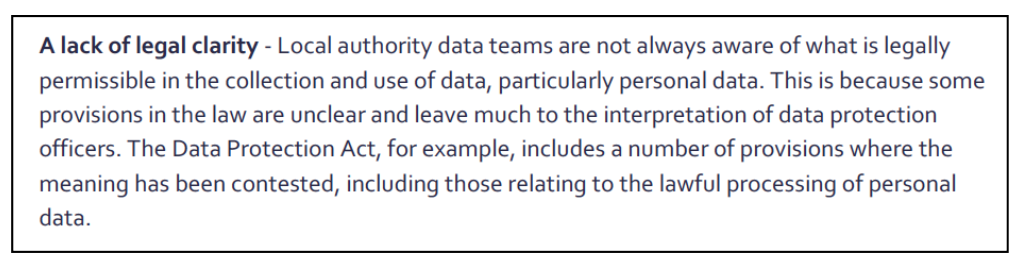

The CDEI Report says both that participants in their workshops found a lack of legal clarity “in the collection and use of data” and, “Participants finished the Forum by discussing ways of overcoming the barriers to effective and ethical data use.”

Lack of understanding of the law is a lack of competence and capability that I have seen and heard time and time and time again in participants at workshops, events, webinars, some of whom are in charge of deciding what tools are procured and how to implement public policy using administrative data, over the last 5 years. The law on data processing is accessible and generally straightforward.

If your work involves “overcoming barriers” then either there is not competence to understand what is lawful to proceed with confidence using data protections appropriately, or you are trying to avoid doing so. Neither is a good place to be in for public authorities, and bodes badly for the safe, fair, transparent and lawful use of our personal data by them.

But it is also lack of data infrastructure that increases the skills gap and leaves a bigger need to know what is lawful or not, because if your data is held in “excessive use of excel spreadsheets” then you need to make decisions about ‘sharing’ done through distribution of data. Data access can be more easily controlled through role-based access models, that make it clear when someone is working around their assigned security role, and creates an audit trail of access. You reduce risk by distributing access, not distributing data.

The CDEI Report quotes as a ‘concern’ that data access granted under emergency powers in the pandemic will be taken away. This is a mistaken view that should be challenged. That access was *always* conditional and time limited. It is not something that will be ‘taken away’ but an exceptional use only granted because it was temporary, for exceptional purposes in exceptional times. Had it not been time limited, you wouldn’t have had access. Emergency powers in law are not ‘taken away’, but can only be granted at all in an emergency. So let’s not get caught up in artificial imaginings of what could change and what ifs, but change what we know is necessary.

We would do well to get away from the hyperbole of being world-leading, and aim for a minimum high standard of competence and capability in all staff who have any data decision-making roles and invest in the basic data infrastructure they need to do a good job.

Appropriate standards to frame the future governance of data

The AI Council Roadmap suggested that, “The UK should lead in developing appropriate standards to frame the future governance of data.” Let’s stop and really think for a minute, what did the Roadmap writers think they meant by that?

Because we have law that frames ‘appropriate standards.’ The UK government just seems unable or unwilling to meet it. And not only in these examples, in fact I’d challenge all the business owners on the AI Council to prove their own products meet it.

You could start with the Guidelines on Automated individual decision-making and Profiling for the purposes of Regulation 2016/679 (wp251rev.01). Or consider any of the Policy, recommendations, declarations, guidelines and other legal instruments issued by Council of Europe bodies or committees on artificial intelligence. Or valuable for export standards, ensure respect for the Convention 108 standards to which we are a signed up State party among its over 50 countries, and growing. That’s all before the simplicity of the UK Data Protection Act 2018 and the GDPR.

You could start with auditing current practice for lawfulness. The CDEI Roadmap says, “The CDEI is now working in partnership with local authorities, including Bristol City Council, to help them maximise the benefits of data and data-driven technologies.” I might suggest that includes a good legal team, as I think the Council needs one.

The UK is already involved in supporting the development of guidelines (as I was alongside UK representatives of government and the data regulator the ICO among hundreds of participants in drawing out Convention 108 Guidelines on data processing in education) but to suggest as a nation state that we have the authority to speak on the future governance of data without acknowledging what we should already be doing and where we get it wrong, is an odd place to start.

The current state of reality in various sectors

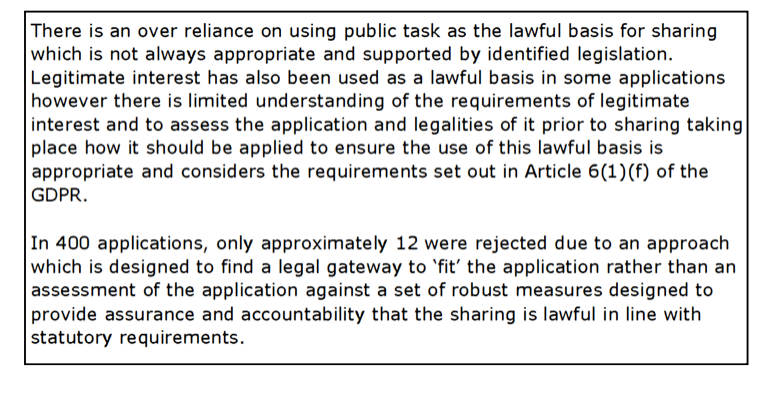

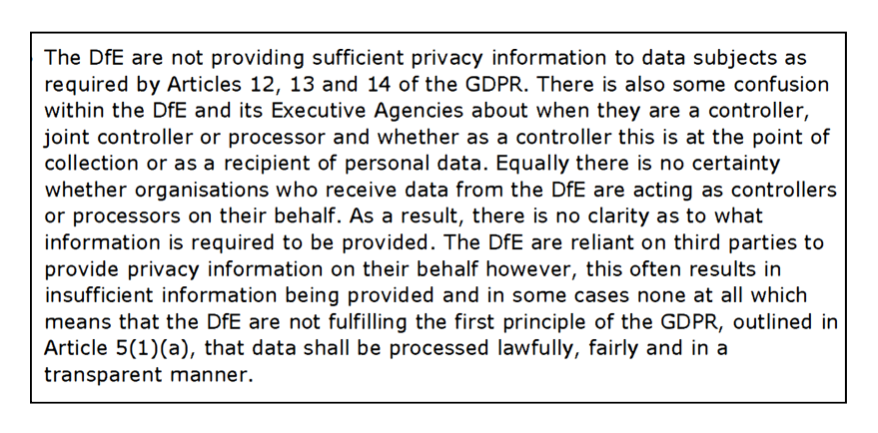

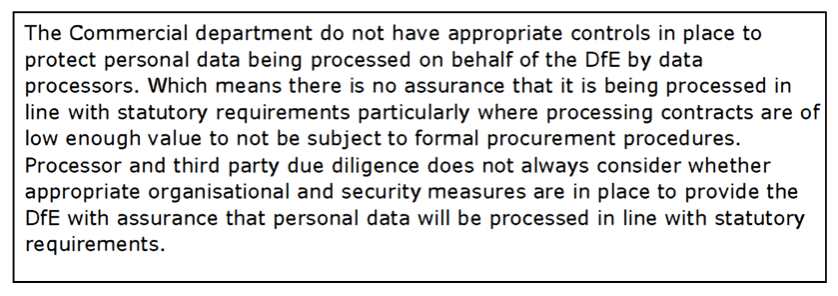

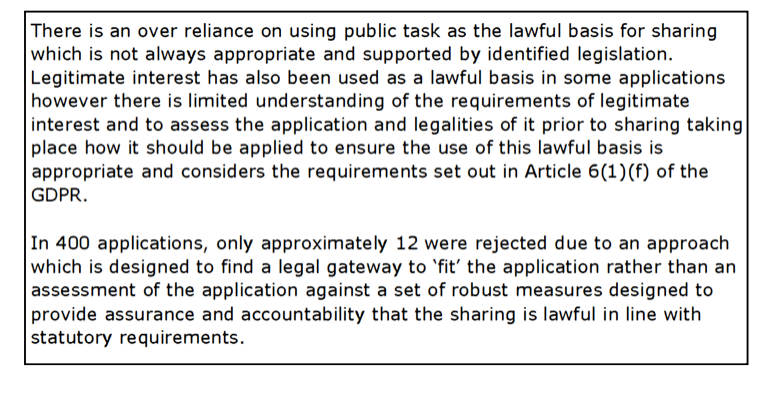

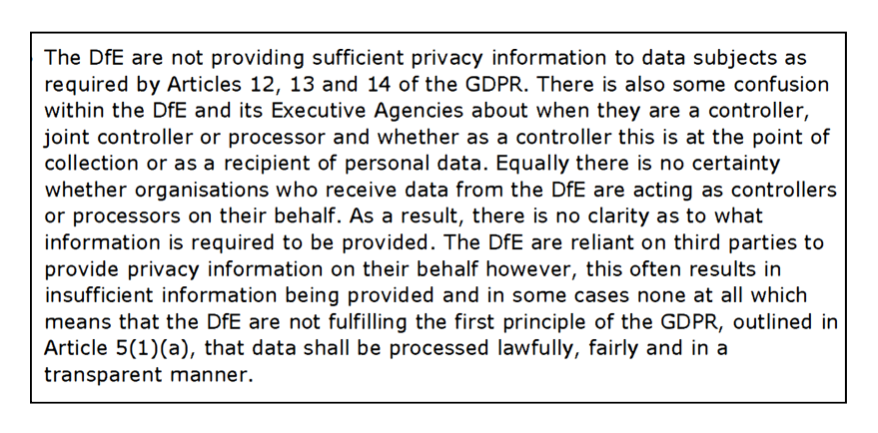

Take for example the ICO audit of the Department for Education.

Failures to meet basic principles of data protection law include knowing what data they’ve got, appropriate controls on distribution and failure to fair process (tell people you process their data). This is no small stuff. And it’s only highlights from the eight page summary.

The DfE don’t adequately understand what data they hold and not having a record of processing leads to a direct breach of #GDPR. Did you know the Department is not able to tell you to which third parties your own or your child’s sensitive, identifying personal data (from over 21m records) was sent, among 1000s of releases?

For too long, the DfE ‘internal cultural barriers and attitudes’ has meant it hasn’t cared about your rights and freedoms or meeting its lawful obligations. That is a national government Department in charge of over fifty such mega databases, the NPD is only one of. This is a systemic and structural set of problems, as a direct result of Ministerial decisions that changed the law in 2012 to give our personal data away from state education. It was a choice made not to tell the people whom the data were about. This continues to be in breach of the law. And that is the same across many government departments.

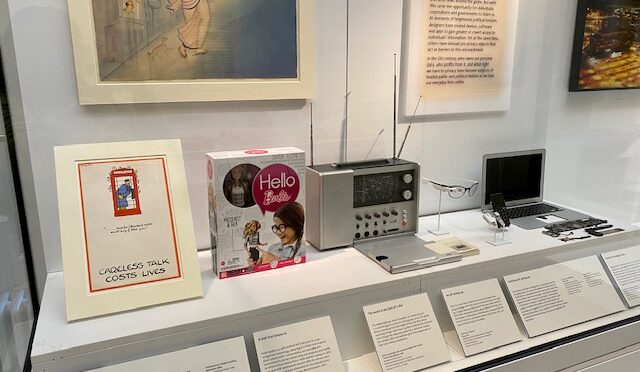

Why does it even matter some still ask? Because there is harm to people today. There is harm in history that must not be possible to repeat. And some of the data held could be used in dangerous ways.

You only need to glance at other applications in government departments and public services to see bad policy, bad data and bad AI or machine learning outcomes. And all of those lead to breakdowns in trust and relations between people and the systems meant to support them, that in turn lead to bad data, and policy.

Unless government changes its approach, the direction of travel is towards less trust, and for public health for example, we see the consequences in disastrous responses from not attending for vaccination based on mistrust of proven data sharing, to COVID conspiracy theories.

Commercial reuse of pubic admin data is a huge mistake and the direction of travel is damaging.

“Survey responses collected from more than 3,000 people across the UK and US show that in late 2018, some 95% of people were not willing to share their medical data with commercial industries. This contrasts with a Wellcome study conducted in 2016 which found that half of UK respondents were willing to do so.” (July 2020, Imperial College)

Mutant algorithms

Misplaced data and misplaced policy aims

In June 2020 The DWP argued in a court case that, “to change the way the benefit’s online computer calculation system worked in line with the original court ruling would undermine the principle of universal credit” — Not only does it fail its public interest purpose, and does harm, but is lax on its own #data governance controls. World leading is far, far, far away.

Entrenched racism

In August 2020 “The Home Office [has] agreed to stop using a computer algorithm to help decide visa applications after allegations that it contained “entrenched racism”. How did it ever get approved for use?

That entrenched racism is found in policing too. The Gangs Matrix use of data required an Enforcement Notice from the ICO and how it continues to operate at all, given its recognised discrimination and harm to young lives, is shocking.

Policy makers seem fixated on quick fixes that for the most part exist only in the marketing speak of the sellers of the products, while ignoring real problems in ethics and law, and denying harm.

“Now is a good time to stop.”

The most obvious case for me, where the Office for AI should step in, and where the CDEI Report from workshops with Local Authorities was most glaringly remiss, is where there is evidence of failure of efficacy and proven risk of danger to life through the procurement of technology in public policy. Don’t forget to ask what doesn’t work.

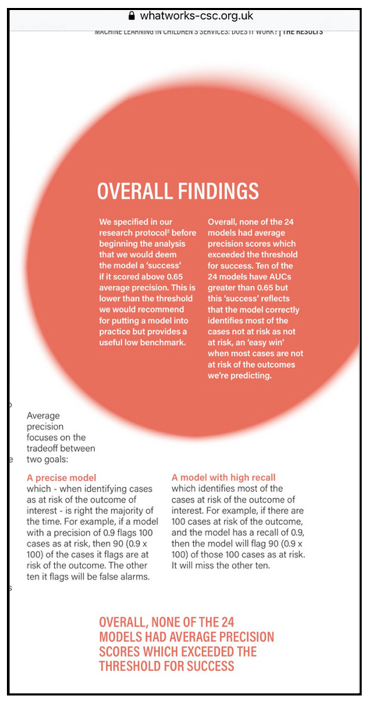

In January 2020 a report from researchers at The Turing institute, Rees Centre and What Works Centre published a report on ethics in Machine Learning in Children’s Social Care (CSC) and raised the “dangerous blind spots” and “lurking biases” in application of machine learning in UK children’s social care— totally unsuitable for life and death situations. Its later evidence showed models that do not work or wuld reach the threshold they set for defining ‘success’.

Out of the thirty four councils who had said they had acute difficulties in recruiting children’s social workers in December 2020 Local Government survey, 50 per cent said they had both difficulty recruiting generally and difficulty recruiting the required expertise, experience or qualification. Can staff in such challenging circumstances really have capacity to understand the limitations of developing technology on top of their every day expertise?

And when it comes to focussing on the data, there are problems too. By focusing on the data held, and using only that to make policy decisions rather than on the ground expertise, we end up in situations where only “those who get measured, get helped”.

As Michael Sanders wrote, on CSC, “Now is a good time to stop. With the global coronavirus pandemic, everything has been changed, all our data scrambled to the point of uselessness in any case.“

There is no short cut

If the Office for AI Roadmap is to be taken seriously outside its own bubble, the board need to be and be seen to be independent of government. It must engage with reality of applied AI in practice in public services, getting basics fixed first. Otherwise all its talk of “doubling down” and suggesting the UK government can build public trust and position the UK as a ‘global leader’ on Data Governance is misleading and a waste of everyone’s time and capacity.

I appreciate that it says, “This Roadmap and its recommendations reflects the views of the Council as well as 100+ additional experts.” All of whom I imagine are more expert than me. If so, which of them is working on fixing the basic underlying problems with data governance within public sector data, how and by when? If they are not, why are they not, and who is?

The CDEI report published today identified in local authorities that, “public consultation can be a ‘nice to have’, as it often involves significant costs where budgets are already limited.” If it’s a position the CDEI does not say is flawed, it may as well pack up and go home. On page 27 it reports, “When asked about their understanding of how their local council is currently using personal data and presented with a list of possible uses, 39% of respondents reported that they do not know how their personal data is being used.” The CDEI should be flagging this with a great big red pen as an indicator of unlawful practice.

The CDEI Report also draws on the GDS Ethical Framework but that will be forever flawed as long as its own users, not the used, are the leading principle focus, underpinning the aims. It starts with “Define and understand public benefit and user need.” There’s very little about ethics and it’s much more about “justifying our project”.

The Report did not appear to have asked the attendees what impact they think their processes have on everyday lives, and social justice.

Without fixes in these approaches, we will never be world leading, but will lag behind because we haven’t built the safe infrastructure necessitated by our vast public administrative data troves. We must end bad data practice which includes getting right the basic principles on retention and data minimisation, and security (all of which would be helped if we started by reducing those ‘vast public administrative data troves’ much of which ranges from poor to abysmal data quality anyway). Start proper governance and oversight procedures. And put in place all the communication channels, tools, policy and training to make telling people how data are used and fair processing happen. It is not, a ‘nice to have’ but is required in all data processing laws around the world.

Any genuine “barriers” to data use in data protection law, are designed as protections for people; the people the public sector, its staff and these arms length bodies are supposed to serve.

Blaming algorithms, blaming lack of clarity in the law, blaming “barriers” is avoidance of one thing. Accountability. Accountability for bad policy, bad data and bad applications of tools is a human responsibility. The systems you apply to human lives affect people, sometimes forever and in the most harmful ways.

What would I love to see led from any of these arms length bodies?

- An audit of existing public admin data held, by national and local government, and consistent published registers of databases and algorithms / AI / ML currently in use.

- Expose where your data system is nothing more than excel spreadsheets and demand better infrastructure.

- Identify the lawful basis for each set of data processes, their earliest records dates and content.

- Publish that resulting ROPA and the retention schedule.

- Assign accountable owners to databases, tools and the registers.

- Sort out how you will communicate with people whose data you unlawfully process to meet the law, or stop processing it.

- And above all, publish a timeline for data quality processes and show that you understand how the degradation of data accuracy, quality, and storage limitations all affect the rights and responsibilities in law that change over time, as a result.

There is no short cut, to doing a good job, but a bad one.

If organisations and bodies are serious about “good data” use in the UK, they must stop passing the buck and spreading the hype. Let’s get on with what needs fixed.

In the words of Gavin Freeguard, then let’s see how it goes.