“If our health records should sail off in the flagship care.data programme, on the sea of commercial Big Data, are we confident that there is consent, fair processing, transparency, accountability, security and good governance? We must know that these basic mainstays are in place, to give it our support.”

“He that filches from me my good name, robs me of that which not enriches him, and makes me poor indeed.” William Shakespeare, Othello

I read this Shakespeare quote last week, not in the original but in the statement Data Brokers: A Call for Transparency and Accountability by US Commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission Julie Brill, May 27 2014. [1] . Since then I have tried to piece together a lay consumer understanding, of how this commercial data market works and how our health records fit in. Experts in data markets and many others will undoubtedly see how naïve it is. But by sharing my ordinary understanding as a mother who is thinking about the impacts of my shopping habits and upcoming care.data decision will have on my children’s future, perhaps I can highlight how trusting we are, and why those governing our data need to ensure the processes around our data are worthy of that trust.

The Commissioner begins:

“Data brokers gather massive amounts of data, from online and offline sources, and combine them into profiles about each of us. Data brokers examine each piece of information they hold about us – where we live, where we work and how much we earn, our race, our daily activities (both off line and online), our interests, our health conditions and our overall financial status – to create a narrative about our past, present and even our future lives. Perhaps we are described as “Financially Challenged” or instead as “Bible Lifestyle.”

Perhaps we are also placed in a category of “Diabetes Interest” or “Smoker in Household.” Data brokers’ clients use these profiles to send us advertisements we might be interested in, an activity that can benefit both the advertiser and the consumer. But these profiles can also be used to determine whether and on what terms companies should do business with us as individual consumers, and could result in our being treated differently based on characteristics such as our race, income, or sexual orientation. If data broker profiles are based on inaccurate information or inappropriate classifications, or used for inappropriate purposes, the profiles have the ability to not only rob us of our good name, but also to lead to lost economic opportunities, higher costs, and other significant harm.”

This is why it matters what is being done at break-neck pace to extract and share our health records in England.

I believe we are not yet sufficiently aware of how our data is used by these intermediaries, and if we were, we’d be horrified. We are complicit consumers in how our data is used with minimal understanding. We’re prepared to unwittingly trade a little privacy with the supermarket, to get our discount vouchers through the post. But we don’t look beyond that to understand what price we are paying and how our commercial interests may be harmed, in much more significant ways than £10 discount or a Legoland entry may compensate. Just like our food, the public are complicit [2] in our own downfall, accepting the marketing spin. We don’t understand credit ratings [3] and risk scores, and even if we do, most consumers don’t know data brokers offer companies scores for other purposes unrelated to credit in an onward chain of reselling. Data can be inaccurate, we are unaware of how to manage or correct it, how we are labelled by it, what opportunities it may restrict as highlighted in the report. We should be better informed.

I’ve recently learned how these, “powerful cross-channel consumer classifications help companies understand the demographics, lifestyles, preferences and behaviours of the UK adult population in extraordinary detail.” [4] demonstrated by Experian.

That they understand and track my behaviours probably better than I do, and at such detailed level, I find surprising and invasive. “Within rural areas we are able to pick out the individual households that are likely to be commuting to towns and cities nearby…” I’ll go more into that later.

It has come to the attention of the general public, only in the last 6 months, that our hospital episode statistics (HES) and data from other secondary care sources, have been on sale in this consumer market. As I said in a previous post [5], a year ago, in April 2013, The ‘Health and Social Care Transparency Panel’ discussion on sharing patient data with information intermediaries stated at that time, there was no legitimate or statutory basis to share at least ONS data [6] in that way for commercial purposes:

“The issues of finding a legitimate basis for sharing ONS death data with information intermediaries for commercial purposes had been a long running problem…The panel identified this as a significant barrier to developing a vibrant market of information intermediaries.”

Some of that data goes back into our health market as business intelligence, both for NHS and private use, for benchmarking, comparisons and making commercial decisions. In our commissioning based marketplace [9], now becoming normalised.

Through the press earlier this year, and the first data release register [10] we have come to understand in part, who is using it and at least in part, how. Aside from bone fide public health planners and health researchers, and the intermediaries using data for commissioning support tools, recipients include these commercial companies and third-party intermediaries exploiting the data as a commodity. Organisations which may buy raw data and sell it on, or process it and sell that data mined information onwards. Organisations after which, Chair Kingsley Manning told the Health Select Committee, [11] we have no idea whom all the end users may be. He indicated the progress that is needed and that HSCIC is already working on improvements, stating the view that “the process HSCIC inherited was no longer robust. ” Q285

“Kingsley Manning: I realise that, and may I come back to that? That is why, specifically with regard to the sets of data that are covered by data-sharing agreements, I took the view that the process that we inherited was no longer robust. We have therefore been in the process of changing the management and the processes, and we have voluntarily adopted a process of being much more transparent about the process and about the data releases we have made.

Q286Barbara Keeley: But what I was trying to get to was the concern. We are just looking for transparency and honesty here. On all the data that was previously released through these commercial reuse licences where there are end users—the question that the Committee wanted to put to you—you are unable to say what are the uses to which the data release under those licences may be put, what controls are in place and what information is provided—you don’t know. With the whole 13 years of the HES database and however many million records have gone out to one of these providers that then provides on to others—in the United States, this has involved putting up the data on Google cloud, and we are not sure of the security of that—you can’t say. You should admit it now. If you can’t tell us where all that data is and what all its uses are, it seems you can’t. You have already admitted that entirely commercial market uses—

Kingsley Manning: The control is through both the overriding regulations established within the Data Protection Act and the data-sharing agreements that we enter into with people, which specifically allow the reuse of data with safeguards with regard to anonymity.

Q287Barbara Keeley: So you have no idea who the end user is. You have no idea if they are using it properly because there is no audit.

Kingsley Manning: And that is in accordance with the law and the regulations as they stand today.

Q288Barbara Keeley: So, just to be clear, audit is not going to be possible for all the uses and all the end users. The data is out there. You have licensed people to use it and other people to buy it, and there is no control over that—it is just out there.

Kingsley Manning: I don’t accept there is no control. There is control established in accordance with law and the regulations as they are today.

Q289Barbara Keeley: But you are not able to say who is using it and for what reason. You are not able to say that. There are end users out there.

Kingsley Manning: No, because we have a large range of organisations that we have been encouraging. Government policy has for a long time been to encourage the use of this data to advance both the health and social care system in this country and the economy. If, for example, we supply pseudonymised data to a drug company to help it to develop a new drug, we do not know the end users beyond that organisation, but that is perceived as being a task and a function that we have. It is done in such a manner that the data is safe and secure, and is not identifiable back to an individual.

You may wish to change the base upon which we act. We absolutely welcome the suggestion that we should submit these to the confidentiality advisory group. We have identified a number of cases where we think its guidance would be very helpful, including in this area. We would absolutely welcome that, but I am afraid we cannot make up the rules that we act by.”

This is what concerns me, if the purposes and permissions granted for care.data are to be defined by the reason why recipients get data for the “promotion of health ” [12] and that their worthiness to receive data is based on, a wooly, undefined notion of whether it will improve care or promote health. It cannot be transparently judged if many users of data are intermediaries with re-use licences, if even the HSCIC doesn’t know who all the end users are, and does not routinely audit them. Nor can anyone know how identifiable therefore the accumulated data sets may be.

If HSCIC does not track each release, each time, each recipient receives data, how do they know every time a new request is granted, how much of the jigsaw puzzle for any given individual, is left to complete?

If you don’t know who they are, how can you govern them and what they do with our data? How on earth can anyone judge how they will be for purposes in the Care Bill 2014 of:

(a)the provision of health care or adult social care, or

(b)the promotion of health.

How can the data controllers judge whether that release, together with all the data these companies already hold, will not do us ‘significant harm’ in the words of Commissioner Brill, of the Federal Trade Commission? Will it not by its nature of labels discriminate against segments of our society, whom the data owners select, based on information beyond our visibility or control? Is society which is segmented and stratified at risk of every increasing inequality? Disability groups for example, may feel at increased risk of stigma or exclusion. David Gillon [13] addresses this in his post here. How can individuals determine if releasing our data to these companies is in our own, or the public interest [14]?

Impossible if we don’t know who they are, and we don’t know what they already hold. A model which is hardly transparent nor conducive to trust.

Dr.Neil Bhatia in Hampshire, a GP who founded the non-commercial website care-data.info, asked HSCIC in an FOI request for the data *about him* which was released to these type of intermediaries. He was told this week, that the data controller, the Health and Information Centre, does not know. We can then only surmise, if our individual data was contained in pseudonymous bulk data transfers in which there remains ‘a latent risk’ of identification. So from the released data register, we should look at what types of companies are using pseudonymous data. We are also told that penalties may be imposed, or even ‘one strike and you’re out’ for misuse of data. Until now at least without robust audit procedures, I believe we’d never know. So how could data be better secured?

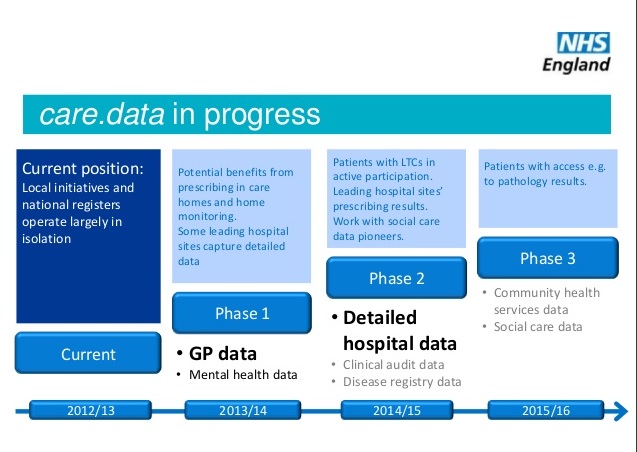

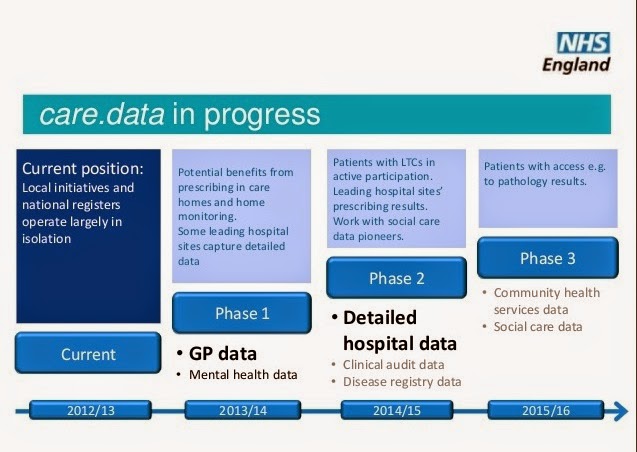

There is talk of a ‘fume cupboard’ access, [15] or giving customers data only in query format, instead of giving out raw chunks of the database. But the Care Bill certainly didn’t legislate for any changes in those types or indeed any governance procedures. We can only wait and see if talk becomes reality and how we can trust it becomes a secure policy and stays so, after we entrust our data. There is no delete button after all.

The Secretary of State wrote on April 25th [16], asking to ensure current practices are up to the task, but as polite as it is, a letter is no form of governance. On June 12th, HSJ [17] reported that the HSCIC has ordered a significant number of trusts to “promptly” delete a series of datafields, which it claims could put patients at risk of being identified, because some of the information in “secondary uses service” that they had submitted to the agency had been entered in an incorrect way over ten years. The good news in this, is it would appear progress is being made in audit, and these errors are being addressed.

However, it highlights the issue created when you release raw data beyond your control. It will mean that organisations who should not have received data, did. How now is that data to be removed from information into which it has become? It will now no longer be raw numbers, but be in graphs, comparative studies and have been inexorably merged with other data. Unlike Cinderella’s carriage, it’s not an automatic process that the raw materials, the data, returns to its previous state after it has become enhanced, turned into business intelligence. The raw files may be traced, removed and deleted, but the knowledge it has turned into, will be almost impossible to find and delete. The links between the two may have disappeared into thin air. Harder to find, than the owner of the glass slipper. An impossible audit trail.

An audit process on leaving the trusts and upon arrival at HSCIC and on leaving HSCIC – at least a three place checkpoint – is what I would have been familiar with in the past for payroll & personal data. It seems that audit procedures for our health records, have just not kept up with the speed at which the data has been sent out on the open seas, and there has been no audit.

“Q287Barbara Keeley: So you have no idea who the end user is. You have no idea if they are using it properly because there is no audit.

Kingsley Manning: And that is in accordance with the law and the regulations as they stand today.”

It’s not to say there are no controls. We are told that data sharing agreements prevent data provided being matched with other data held, which prevents making individuals identifiable. However, as I’ll look at in my next post, I don’t think it even has to get the the person level to be sufficiently identifiable as to be discriminatory. The segmenting of society at group level, at household level, with detailed understanding of our behaviours, is sufficient, aside from the identifiable individual level data these companies hold for identity verification and so on. When companies extract and store raw data, we have no idea where and with whom it lands up. I’ve been completely surprised by what I have learned in the last few weeks how these third parties use our data.

The current controls around and governance of our health data remains unchanged by the Care Bill. Through policy, law and directions the HSCIC has

…”licensed people to use it and other people to buy it, and there is no control over that.” [12]

As Sir Manning said,

…”because we have a large range of organisations that we have been encouraging. Government policy has for a long time been to encourage the use of this data”

Controls may be in line with policy and the law, but I believe it simply hasn’t kept up with the functional need for a decent governance framework.

Julie Brill’s Statement made a recommendation:

“A second accountability measure that Congress should consider is to require data brokers to take reasonable steps to ensure that their original sources of information obtained appropriate consent from consumers.”

Accountability in the UK of these data brokers seems quite absent in real terms, unknown to the public at large.

The same core issue identified by Julie Brill in the US, lack of informed consent. If we don’t know you have it, how can we ask to check if it’s correct or who uses it? In an era of borderless electronic data transfers, we should seek to put in place the highest standards as common denominators, and in terms of privacy, there are lessons worth learning from the US actions post Snowden which in the UK, we have not yet begun.

If our health records should sail off in the flagship care.data programme, on the sea of commercial Big Data, are we confident that there is consent, fair processing, transparency, accountability, security and good governance? We must know that these basic mainstays are in place, and will stay so in future, to give it our support. Well governed data is more likely to get our trust, therefore our consent and be of better quality for buyers.

We must also not forget to clarify why it is our records are needed in the broad and undefined care.data scope that we still have not seen pinned down. Is the public good really defined for care.data and does it outweigh the private long established rights of consent and confidentiality? Do we trust these commercial company uses to do “no harm” as the US Commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission examined?

…”the profiles have the ability to not only rob us of our good name, but also to lead to lost economic opportunities, higher costs, and other significant harm.”

When we visit a medic we are vulnerable, ill or in need of help. We entrust our knowledge in confidence, and trust it will be used for our care. A whole hotchpotch of other indirect uses, including commercial exploitation is not what we expect. We need to trust the data we give away to local staff, is processed appropriately all the way up the data chain, when it is stored, when it is released and beyond. For now at least, it appears citizens can only control the one point at which we first give our data up. After that, we have faith that those governing our data ensure the processes around its management are worthy of that trust. The governance processes that go beyond the HSCIC control, will directly influence that trust, and our care.data decision to object, or not.

For citizens to see this still precarious commercial hull, and trust that our innermost confidences should be safe within it, is stretching our trust, just a little too far. The knowledge of our health and lifestyle should not be commercially exploited in this uncontrollable marketplace by data brokers without our knowledge and consent. Health data is on the cusp of including more widespread biomedical data. In my children’s lifetime that may be a whole new era of data management to contend with. For now, all this intensive data mining may be much more than we already imagined and we should carefully consider how society will be affected if it includes every aspect of our health and lifestyle data. It may be yet another aspect of individual surveillance more than society can stand.[18]

The care.data storm may not yet be over.

*****

In part three on commercial uses, I’m going to explore, from my lay perspective, on how some of these intermediaries and data processing companies, use data concretely in practice. As Julie Brill says how these intermediaries, “create a narrative about our past, present and even our future lives.”

******

[1] Data Brokers: A call for transparency and accountability – http://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/311551/140527databrokerrptbrillstmt.pdf

[2] Food Marketing film by Catsnake with Actress Kate Miles via Upworthy http://www.upworthy.com/no-one-applauds-this-woman-because-theyre-too-creeped-out-at-themselves-to-put-their-hands-together

[3] Your Credit Ratings explained BBC http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/2963580.stm

[4] “Mosaic is Experian’s most comprehensive cross-channel classification system …it helps you understand consumers in extraordinary detail.” http://www.experian.co.uk/marketing-services/products/mosaic/mosaic-in-detail.html

[5] Flagship care.data – Commercial Uses in theory: https://jenpersson.com/flagship-care-data-precious-cargo-1-commercial-uses-in-theory/

[6] Health and Social Care transparency panel:- minutes from 23rd April 2013 – https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/259828/HSCTP_13-1-mins_23_Apr_13__NewTemp_.pdf

[7] 17th March Omega Solver in the Guardian, by Randeep Ramesh http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/mar/17/online-tool-identify-public-figures-medical-care

[8] 16th March Harvey Walsh in the Sunday Times by Jon Ungoed-Thomas ‘healthcare intelligence company, has paid for a database’ http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/uk_news/Health/article1388324.ece

[9] The Privatisation of the NHS Prof.A.Pollock at Tedex event

[10] HSCIC Data Register http://www.hscic.gov.uk/dataregister

[11} Evidence at Parliamentary Health Select Committee April 8th 2014: http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/health-committee/handling-of-nhs-patient-data/oral/8416.html

[12] Care Bill 2014 – Enacted: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/section/122/enacted

[13] care.data in their own words – D. Gillon Where’s the Benefit? http://wheresthebenefit.blogspot.co.uk/2014/03/caredata-in-their-own-words.htm

[14] Public vs Private interest – Dr. M Taylor, “Information Governance as a Force for Good? Lessons to be Learnt from Care.data”, (2014) 11:1 SCRIPTed

[15] Fume Cupboard access in NHS England stakeholder letter April 14th 2014

[16] Letter from Jeremy Hunto HSCIC regarding patient confidentiality

[17] Health Service Journal, June 12th, Nick Renaud-Komiya, http://www.hsj.co.uk/news/trusts-ordered-to-delete-incorrect-data/5071902.article?blocktitle=News&contentID=8805

[18] John Naughton, Observer 8th June, http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/jun/08/big-data-mined-real-winners-nsa-gchq-surveillance