Since the beginning of time and the story of the Garden of Eden, man has found a way to share knowledge and its power.

Modern digital tools have become the everyday way to access knowledge for many across the world, giving quick access to information and sharing power more fairly.

In this third part of my thoughts on digital revolution by design, triggered by the #kfdigi15 event on June 16-17, I’ve been considering some of the constructs we have built; those we accept and those that could be changed, given the chance, to build a better digital future.

Not only the physical constructions, the often networked infrastructures, but intangible infrastructures of principles and power, co-dependencies around a physical system; the legal and ethical infrastructures of ownership, governance and accountability.

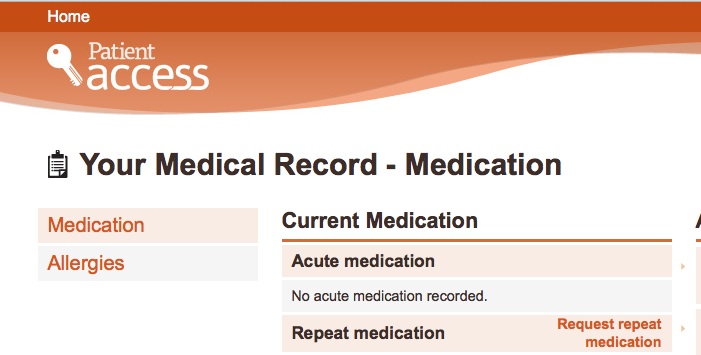

Our personal data flow in systems behind the screens, at the end of our fingertips. Controlled in frameworks designed by providers and manufacturers, government and commercial agencies.

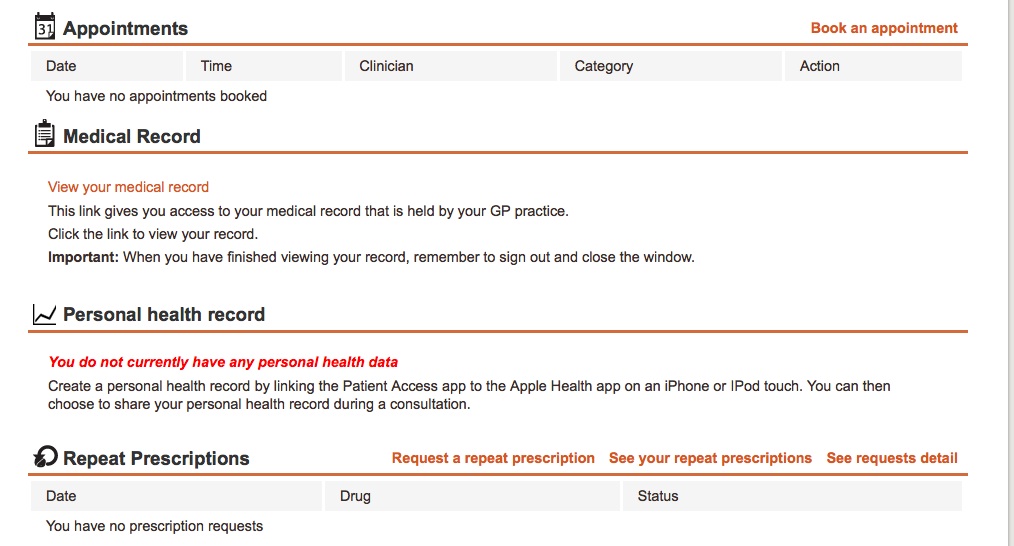

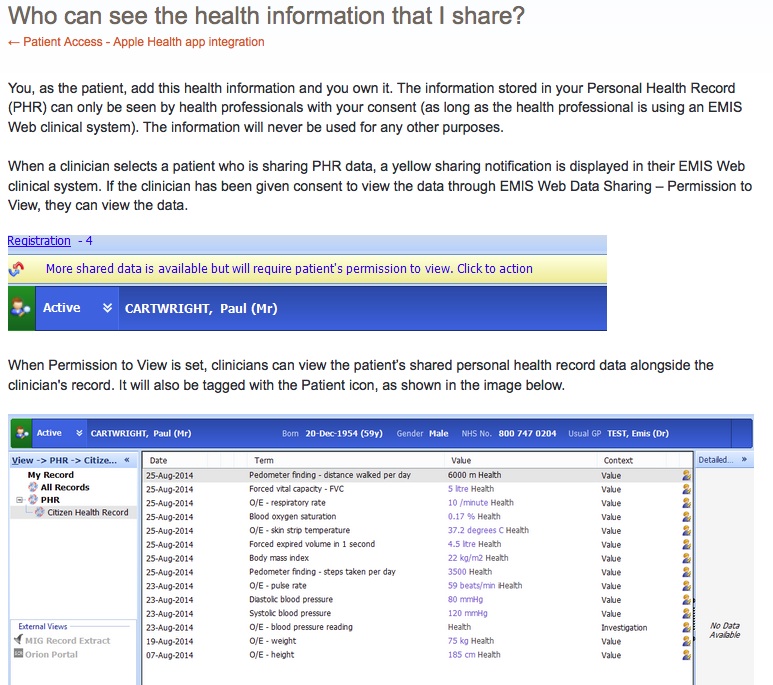

Increasingly in digital discussions we hear that the data subject, the citizen, will control their own data.

But if it is on the terms and conditions set by others, how much control is real and how much is the talk of a consenting citizen only a fig leaf behind which any real control is still held by the developer or organisation providing the service?

When data are used, turned into knowledge as business intelligence that adds value to aid informed decision making. By human or machine.

How much knowledge is too much knowledge for the Internet of Things to build about its users? As Chris Matyszczyk wrote:

“We have all agreed to this. We click on ‘I agree’ with no thought of consequences, only of our convenience.”

Is not knowing what we have agreed to our fault, or the responsibility of the provider who’d rather we didn’t know?

Citizens’ rights are undermined in unethical interactions if we are exploited by easy one-click access and exchange our wealth of data at unseen cost. Can it be regulated to promote, not stifle innovation?

How can we get those rights back and how will ‘doing the right thing’ help shape and control the digital future we all want?

The infrastructures we live inside

As Andrew Chitty says in this HSJ article: “People live more mobile and transient lives and, as a result, expect more flexible, integrated, informed health services.”

To manage that, do we need to know how systems work, how sharing works, and trust the functionality of what we are not being told and don’t see behind the screens?

At the personal level, whether we sign up for the social network, use a platform for free email, or connect our home and ourselves in the Internet of things, we each exchange our personal data with varying degrees of willingness. There there is often no alternative if we want to use the tool.

As more social and consensual ‘let the user decide’ models are being introduced, we hear it’s all about the user in control, but reality is that users still have to know what they sign up for.

In new models of platform identity sign on, and tools that track and mine our personal data to the nth degree that we share with the system, both the paternalistic models of the past and the new models of personal control and social sharing are merging.

Take a Fitbit as an example. It requires a named account and data sharing with the central app provider. You can choose whether or not to enable ‘social sharing’ with nominated friends whom you want to share your boasts or failures with. You can opt out of only that part.

I fear we are seeing the creation of a Leviathan sized monster that will be impossible to control and just as scary as today’s paternalistic data mis-management. Some data held by the provider and invisibly shared with third parties beyond our control, some we share with friends, and some stored only on our device.

While data are shared with third parties without our active knowledge, the same issue threatens to derail consumer products, as well as commercial ventures at national scale, and with them the public interest. Loss of trust in what is done behind the settings.

Society has somehow seen privacy lost as the default setting. It has become something to have to demand and defend.

“If there is one persistent concern about personal technology that nearly everybody expresses, it is privacy. In eleven of the twelve countries surveyed, with India the only exception, respondents say that technology’s effect on privacy was mostly negative.” [Microsoft survey 2015, of 12,002 internet users]

There’s one part of that I disagree with. It’s not the effect of technology itself, but the designer or developers’ decision making that affects privacy. People have a choice how to design and regulate how privacy is affected, not technology.

Citizens have vastly differing knowledge bases of how data are used and how to best interact with technology. But if they are told they own it, then all the decision making framework should be theirs too.

By giving consumers the impression of control, the shock is going to be all the greater if a breach should ever reveal where fitness wearable users slept and with whom, at what address, and were active for how long. Could a divorce case demand it?

Fitbit users have already found their data used by police and in the courtroom – probably not what they expected when they signed up to a better health tool. Others may see benefits that could harm others by default who are excluded from accessing the tool.

Some at org level still seem to find this hard to understand but it is simple:

No trust = no data = no knowledge for commercial, public or personal use and it will restrict the very innovation you want to drive.

Google gmail users have to make 10+ clicks to restrict all ads and information sharing based on their privacy and ad account settings. The default is ad tailoring and data mining. Many don’t even know it is possible to change the settings and it’s not intuitive how to.

Firms need to consider their own reputational risk if users feel these policies are not explicit and are exploitation. Those caught ‘cheating’ users can get a very public slap on the wrist.

Let the data subjects rule, but on whose terms and conditions?

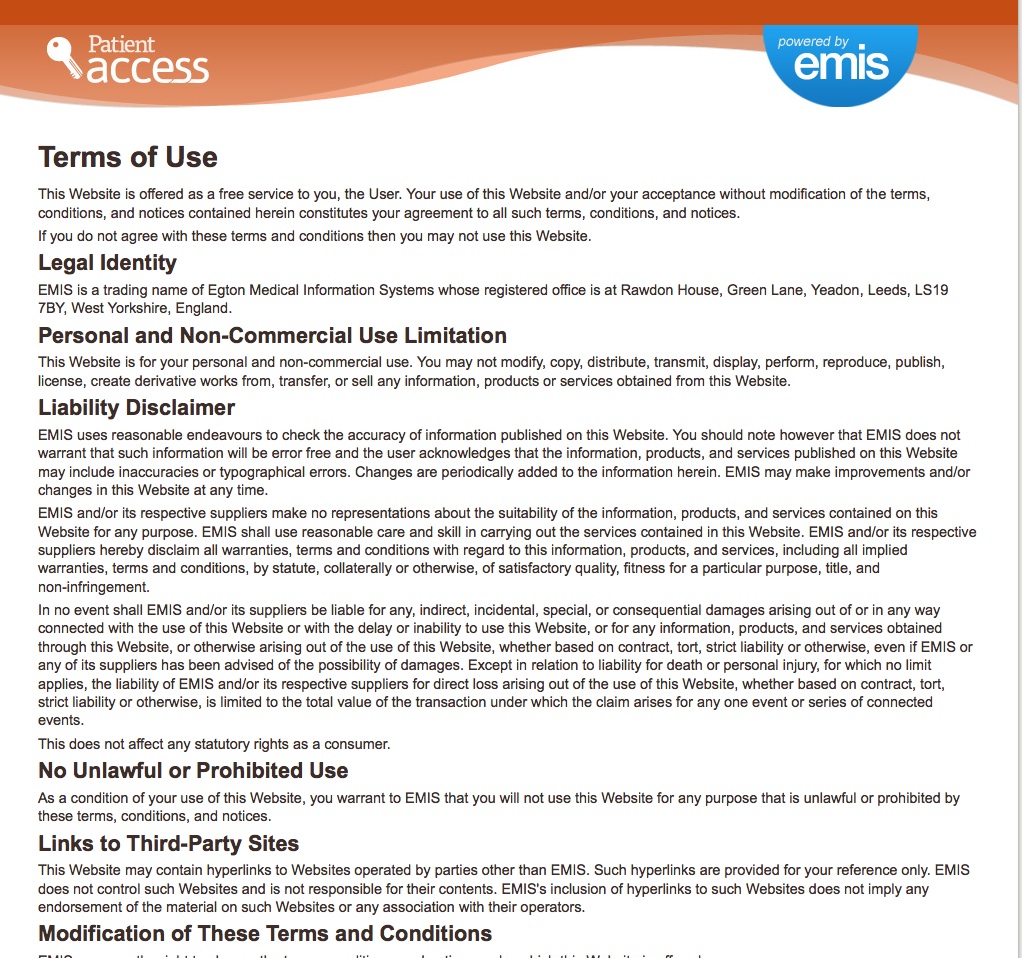

The question every citizen signing up to digital agreements should ask, is what are the small print and how will I know if they change? Fair processing should offer data protection, but isn’t effective.

If you don’t have access to information, you make decisions based on a lack of information or misinformation. Decisions which may not be in your own best interest or that of others. Others can exploit that.

And realistically and fairly, organisations can’t expect citizens to read pages and pages of Ts&Cs. In addition, we don’t know what we don’t know. Information that is missing can be as vital to understand as that provided. ‘Third parties’ sharing – who exactly does that mean?

The concept of an informed citizenry is crucial to informed decision making but it must be within a framework of reasonable expectation.

How do we grow the fruits of knowledge in a digital future?

Real cash investment is needed now for a well-designed digital future, robust for cybersecurity, supporting enforceable governance and oversight. Collaboration on standards and thorough change plans. I’m sure there is much more, but this is a start.

Figurative investment is needed in educating citizens about the technology that should serve us, not imprison us in constructs we do not understand but cannot live without.

We must avoid the chaos and harm and wasted opportunity of designing massive state-run programmes in which people do not want to participate or cannot participate due to barriers of access to tools. Avoid a Babel of digital blasphemy in which the only wise solution might be to knock it down and start again.

Our legislators and regulators must take up their roles to get data use, and digital contract terms and conditions right for citizens, with simplicity and oversight. In doing so they will enable better protection against risks for commercial and non-profit orgs, while putting data subjects first.

To achieve greatness in a digital future we need: ‘people speaking the same language, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them’.

Ethics. It’s more than just a county east of London.

Let’s challenge decision makers to plant the best of what is human at the heart of the technology revolution: doing the right thing.

And from data, we will see the fruits of knowledge flourish.

******

1. Digital revolution by design: building for change and people

2. Digital revolution by design: barriers by design

3. Digital revolution by design: infrastructures and the fruits of knowledge

4. Digital revolution by design: infrastructures and the world we want