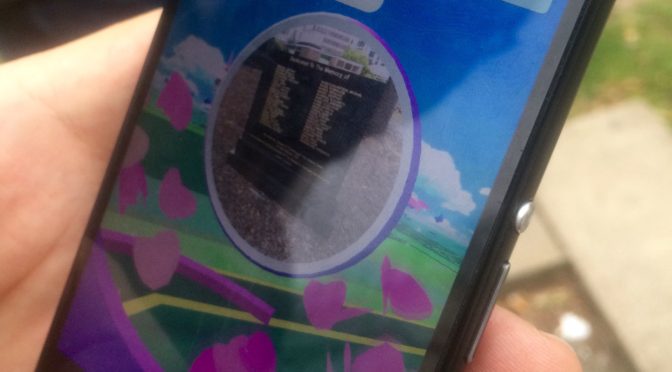

I caught my first Pokémon and I liked it. Well, OK, someone else handed me a phone and insisted I have a go. Turns out my curve ball is pretty good. Pokémon GO is enabling all sorts of new discoveries.

Discoveries reportedly including a dead man, robbery, picking up new friends, and scrapes and bruises. While players are out hunting anime in augmented reality, enjoying the novelty, and discovering interesting fun facts about their vicinity, Pokémon GO is gathering a lot of data. It’s influencing human activity in ways that other games can only envy, taking in-game interaction to a whole new level.

And it’s popular.

A Vaporeon popped up in the middle of Central Park and this happenedpic.twitter.com/bSJ6GUvPvh

— Izzy Nobre (@MrNobre) July 16, 2016

But what is it learning about us as we do it?

This week questions have been asked about the depth of interaction that the app gets by accessing users’ log in credentials.

What I would like to know is what access goes in the other direction?

Google, heavily invested in AI and Machine intelligence research, has “learning systems placed at the core of interactive services in a fast changing and sometimes adversarial environment, combinations of techniques including deep learning and statistical models need to be combined with ideas from control and game theory.”

The app, which is free to download, has raised concerns over suggestions the app could access a user’s entire Google account, including email and passwords. Then it seemed it couldn’t. But Niantic is reported to have made changes to permissions to limit access to basic profile information anyway.

If Niantic gets access to data owned by Google through its use of google log in credentials, does Nantic’s investor, Google’s Alphabet, get the reverse: user data from the Google log in interaction with the app, and if so, what does Google learn through the interaction?

Who gets access to what data and why?

Brian Crecente writes that Apple, Google, Niantic likely making more on Pokémon Go than Nintendo, with 30 percent of revenue from in-app purchases on their online stores.

Next stop is to make money from marketing deals between Niantic and the offline stores used as in-game focal points, gyms and more, according to Bryan Menegus at Gizmodo who reported Redditors had discovered decompiled code in the Android and iOS versions of Pokémon Go earlier this week “that indicated a potential sponsorship deal with global burger chain McDonald’s.”

The logical progressions of this, is that the offline store partners, i.e. McDonald’s and friends, will be making money from players, the people who get led to their shops, restaurants and cafes where players will hang out longer than the Pokéstop, because the human interaction with other humans, the battles between your collected creatures and teamwork, are at the heart of the game. Since you can’t visit gyms until you are level 5 and have chosen a team, players are building up profiles over time and getting social in real life. Location data that may build up patterns about the players.

This evening the two players that I spoke to were already real-life friends on their way home from work (that now takes at least an hour longer every evening) and they’re finding the real-life location facts quite fun, including that thing they pass on the bus every day, and umm, the Scientology centre. Well, more about that later**.

Every player I spotted looking at the phone with that finger flick action gave themselves away with shared wry smiles. All 30 something men. There is possibly something of a legacy in this they said, since the initial Pokémon game released 20 years ago is drawing players who were tweens then.

Since the app is online and open to all, children can play too. What this might mean for them in the offline world, is something the NSPCC picked up on here before the UK launch. Its focus of concern is the physical safety of young players, citing the risk of in-game lures misuse. I am not sure how much of an increased risk this is compared with existing scenarios and if children will be increasingly unsupervised or not. It’s not a totally new concept. Players of all ages must be mindful of where they are playing**. Some stories of people getting together in the small hours of the night has generated some stories which for now are mostly fun. (Go Red Team.) Others are worried about hacking. And it raises all sorts of questions if private and public space is has become a Pokestop.

While the NSPCC includes considerations on the approach to privacy in a recent more general review of apps, it hasn’t yet mentioned the less obvious considerations of privacy and ethics in Pokémon GO. Encouraging anyone, but particularly children, out of their home or protected environments and into commercial settings with the explicit aim of targeting their spending. This is big business.

Privacy in Pokémon GO

I think we are yet to see a really transparent discussion of the broader privacy implications of the game because the combination of multiple privacy policies involved is less than transparent. They are long, they seem complete, but are they meaningful?

We can’t see how they interact.

Google has crowd sourced the collection of real time traffic data via mobile phones. Geolocation data from google maps using GPS data, as well as network provider data seem necessary to display the street data to players. Apparently you can download and use the maps offline since Pokémon GO uses the Google Maps API. Google goes to “great lengths to make sure that imagery is useful, and reflects the world our users explore.” In building a Google virtual reality copy of the real world, how data are also collected and will be used about all of us who live in it, is a little wooly to the public.

U.S. Senator Al Franken is apparently already asking Niantic these questions. He points out that Pokémon GO has indicated it shares de-identified and aggregate data with other third parties for a multitude of purposes but does not describe the purposes for which Pokémon GO would share or sell those data [c].

It’s widely recognised that anonymisation in many cases fails so passing only anonymised data may be reassuring but fail in reality. Stripping out what are considered individual personal identifiers in terms of data protection, can leave individuals with unique characteristics or people profiled as groups.

Opt out he feels is inadequate as a consent model for the personal and geolocational data that the app is collecting and passing to others in the U.S.

While the app provider would I’m sure argue that the UK privacy model respects the European opt in requirement, I would be surprised if many have read it. Privacy policies fail.

Poor practices must be challenged if we are to preserve the integrity of controlling the use of our data and knowledge about ourselves. Being aware of who we have ceded control of marketing to us, or influencing how we might be interacting with our environment, is at least a step towards not blindly giving up control of free choice.

The Pokémon GO permissions “for the purpose of performing services on our behalf“, “third party service providers to work with us to administer and provide the Services” and “also use location information to improve and personalize our Services for you (or your authorized child)” are so broad as they could mean almost anything. They can also be changed without any notice period. It’s therefore pretty meaningless. But it’s the third parties’ connection, data collection in passing, that is completely hidden from players.

If we are ever to use privacy policies as meaningful tools to enable consent, then they must be transparent to show how a chain of permissions between companies connect their services.

Otherwise they are no more than get out of jail free cards for the companies that trade our data behind the scenes, if we were ever to claim for its misuse. Data collectors must improve transparency.

Behavioural tracking and trust

Covert data collection and interaction is not conducive to user trust, whether through a failure to communicate by design or not.

By combining location data and behavioural data, measuring footfall is described as “the holy grail for retailers and landlords alike” and it is valuable. “Pavement Opportunity” data may be sent anonymously, but if its analysis and storage provides ways to pitch to people, even if not knowing who they are individually, or to groups of people, it is discriminatory and potentially invisibly predatory. The pedestrian, or the player, Jo Public, is a commercial opportunity.

Pokémon GO has potential to connect the opportunity for profit makers with our pockets like never before. But they’re not alone.

Who else is getting our location data that we don’t sign up for sharing “in 81 towns and cities across Great Britain“?

Whether footfall outside the shops or packaged as a game that gets us inside them, public interest researchers and commercial companies alike both risk losing our trust if we feel used as pieces in a game that we didn’t knowingly sign up to. It’s creepy.

For children the ethical implications are even greater.

There are obligations to meet higher legal and ethical standards when processing children’s data and presenting them marketing. Parental consent requirements fail children for a range of reasons.

So far, the UK has said it will implement the EU GDPR. Clear and affirmative consent is needed. Parental consent will be required for the processing of personal data of children under age 16. EU Member States may lower the age requiring parental consent to 13, so what that will mean for children here in the UK is unknown.

The ethics of product placement and marketing rules to children of all ages go out the window however, when the whole game or programme is one long animated advert. On children’s television and YouTube, content producers have turned brand product placement into programmes: My Little Pony, Barbie, Playmobil and many more.

Alice Webb, Director of BBC Children’s and BBC North, looked at some of the challenges in this as the BBC considers how to deliver content for children whilst adapting to technological advances in this LSE blog and the publication of a new policy brief about families and ‘screen time’, by Alicia Blum-Ross and Sonia Livingstone.

So is this augmented reality any different from other platforms?

Yes because you can’t play the game without accepting the use of the maps and by default some sacrifice of your privacy settings.

Yes because the ethics and implications of of putting kids not simply in front of a screen that pitches products to them, but puts them physically into the place where they can consume products – if the McDonalds story is correct and a taster of what will follow – is huge.

Boundaries between platforms and people

Blum-Ross says, “To young people, the boundaries and distinctions that have traditionally been established between genres, platforms and devices mean nothing; ditto the reasoning behind the watershed system with its roots in decisions about suitability of content. “

She’s right. And if those boundaries and distinctions mean nothing to providers, then we must have that honest conversation with urgency. With our contrived consent, walking and running and driving without coercion, we are being packaged up and delivered right to the door of for-profit firms, paying for the game with our privacy. Smart cities are exploiting street sensors to do the same.

Freewill is at the very heart of who we are. “The ability to choose between different possible courses of action. It is closely linked to the concepts of responsibility, praise, guilt, sin, and other judgments which apply only to actions that are freely chosen.” Free choice of where we shop, what we buy and who we interact with is open to influence. Influence that is not entirely transparent presents opportunity for hidden manipulation, while the NSPCC might be worried about the risk of rare physical threat, the potential for the influencing of all children’s behaviour, both positive and negative, reaches everyone.

Some stories of how behaviour is affected, are heartbreakingly positive. And I met and chatted with complete strangers who shared the joy of something new and a mutual curiosity of the game. Pokémon GOis clearly a lot of fun. It’s also unclear on much more.

I would like to explicitly understand if Pokémon GO is gift packaging behavioural research by piggybacking on the Google platforms that underpin it, and providing linked data to Google or third parties.

Fishing for frequent Pokémon encourages players to ‘check in’ and keep that behaviour tracking live. 4pm caught a Krabby in the closet at work. 6pm another Krabby. Yup, still at work. 6.32pm Pidgey on the street outside ThatGreenCoffeeShop. Monday to Friday.

The Google privacy policies changed in the last year require ten clicks for opt out, and in part, the download of an add-on. Google has our contacts, calendar events, web searches, health data, has invested in our genetics, and all the ‘Things that make you “you”. They have our history, and are collecting our present. Machine intelligence work on prediction, is the future. For now, perhaps that will be pinging you with a ‘buy one get one free’ voucher at 6.20, or LCD adverts shifting as you drive back home.

Pokémon GO doesn’t have to include what data Google collects in its privacy policy. It’s in Google’s privacy policy. And who really read that when it came out months ago, or knows what it means in combination with new apps and games we connect it with today? Tracking and linking data on geolocation, behavioural patterns, footfall, whose other phones are close by, who we contact, and potentially even our spend from Google wallet.

Have Google and friends of Niantic gotta know it all?

![Building Public Trust [5]: Future solutions for health data sharing in care.data](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/caredatatimeline-637x372.jpg)

![Building Public Trust [2]: a detailed approach to understanding Public Trust in data sharing](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Trust-e1426443553441-672x372.jpg)