“With the Family Link app from Google, you can stay in the loop as your kid explores on their Android* device. Family Link lets you create a Google Account for your kid that’s like your account, while also helping you set certain digital ground rules that work for your family — like managing the apps your kid can use, keeping an eye on screen time, and setting a bedtime on your kid’s device.”

John Carr shared his blog post about the Google Family Link today which was the first I had read about the new US account in beta. In his post, with an eye on GDPR, he asks, what is the right thing to do?

What is the Family Link app?

Family Link requires a US based google account to sign up, so outside the US we can’t read the full details. However from what is published online, it appears to offer the following three key features:

“Approve or block the apps your kid wants to download from the Google Play Store.

Keep an eye on screen time. See how much time your kid spends on their favorite apps with weekly or monthly activity reports, and set daily screen time limits for their device. “

and

“Set device bedtime: Remotely lock your kid’s device when it’s time to play, study, or sleep.”

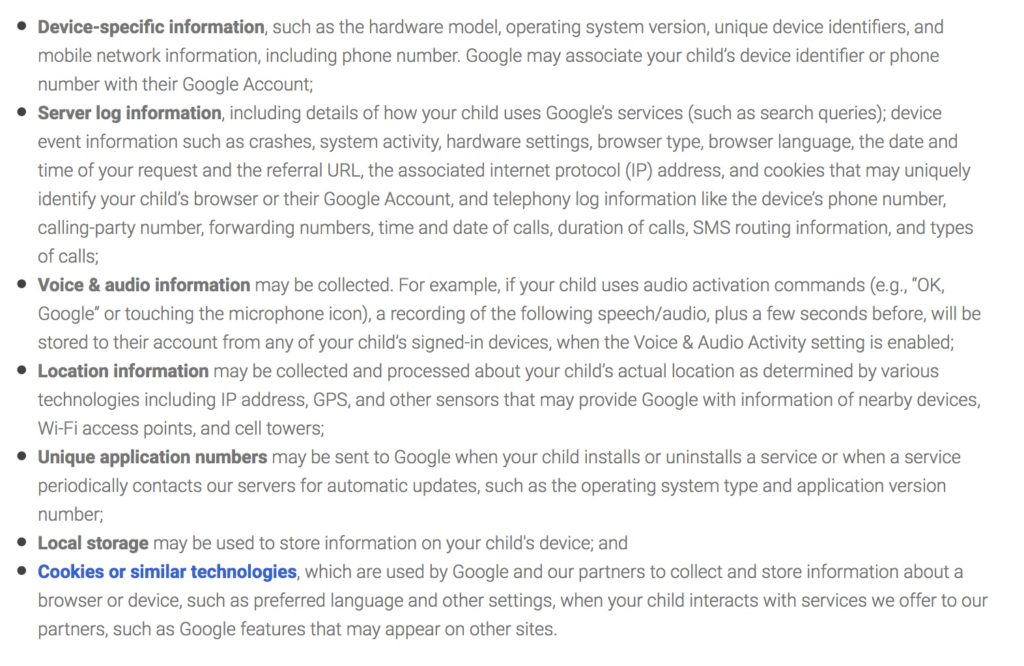

From the privacy and disclosure information it reads that there is not a lot of difference between a regular (over 13s) Google account and this one for under 13s. To collect data from under 13s it must be compliant with COPPA legislation.

If you google “what is COPPA” the first result says, “The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) is a law created to protect the privacy of children under 13.”

But does this Google Family Link do that? What safeguards and controls are in place for use of this app and children’s privacy?

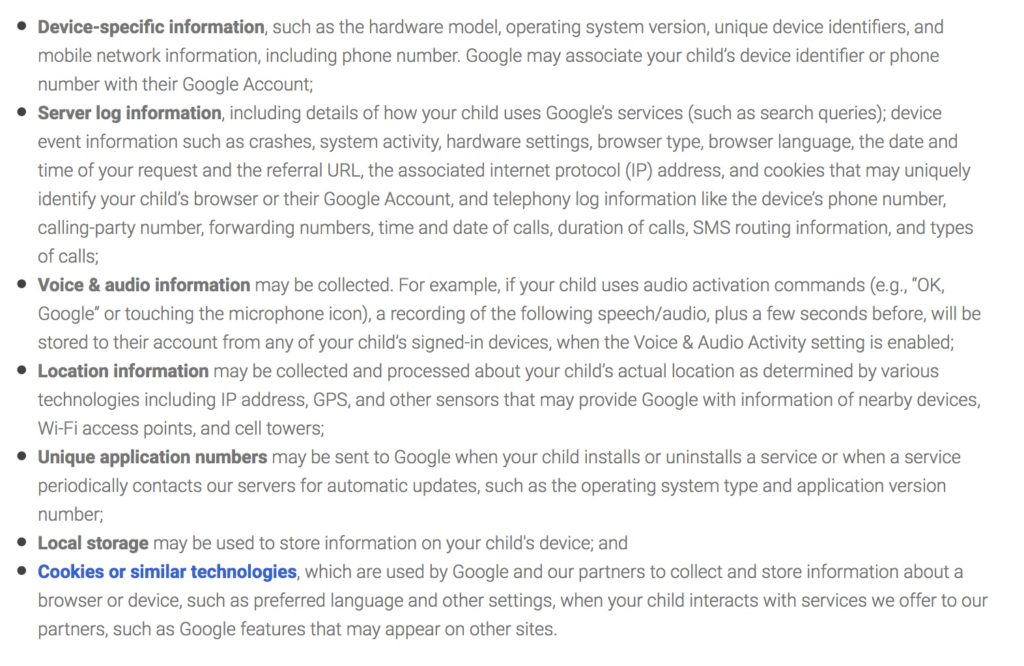

What data does it capture?

“In order to create a Google Account for your child, you must review the Disclosure (including the Privacy Notice) and the Google Privacy Policy, and give consent by authorizing a $0.30 charge on your credit card.”

Google captures the parent’s verified real-life credit card data.

Google captures child’s name, date of birth and email.

Google captures voice.

Google captures location.

Google may associate your child’s phone number with their account.

And lots more:

Google automatically collects and stores certain information about the services a child uses and how a child uses them, including when they save a picture in Google Photos, enter a query in Google Search, create a document in Google Drive, talk to the Google Assistant, or watch a video in YouTube Kids.

What does it offer over regular “13+ Google”?

In terms of general safeguarding, it doesn’t appear that SafeSearch is on by default but must be set and enforced by a parent.

Parents should “review and adjust your child’s Google Play settings based on what you think is right for them.”

Google rightly points out however that, “filters like SafeSearch are not perfect, so explicit, graphic, or other content you may not want your child to see makes it through sometimes.”

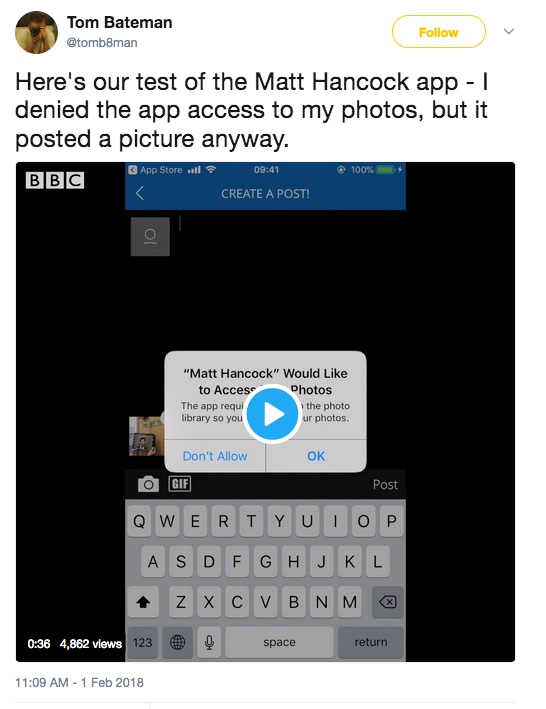

Ron Amadeo at Arstechnica wrote a review of the Family Link app back in February, and came to similar conclusions about added safeguarding value:

“Other than not showing “personalized” ads to kids, data collection and storage seems to work just like in a regular Google account. On the “Disclosure for Parents” page, Google notes that “your child’s Google Account will be like your own” and “Most of these products and services have not been designed or tailored for children.” Google won’t do any special content blocking on a kid’s device, so they can still get into plenty of trouble even with a monitored Google account.”

Your child will be able to share information, including photos, videos, audio, and location, publicly and with others, when signed in with their Google Account. And Google wants to see those photos.

There’s some things that parents cannot block at all.

Installs of app updates can’t be controlled, so leave a questionable grey area. Many apps are built on classic bait and switch – start with a free version and then the upgrade contains paid features. This is therefore something to watch for.

“Regardless of the approval settings you choose for your child’s purchases and downloads, you won’t be asked to provide approval in some instances, such as if your child: re-downloads an app or other content; installs an update to an app (even an update that adds content or asks for additional data or permissions); or downloads shared content from your Google Play Family Library. “

The child “will have the ability to change their activity controls, delete their past activity in “My Activity,” and grant app permissions (including things like device location, microphone, or contacts) to third parties”.

What’s in it for children?

You could argue that this gives children “their own accounts” and autonomy. But why do they need one at all? If I give my child a device on which they can download an app, then I approve it first.

If I am not aware of my under 13 year old child’s Internet time physically, then I’m probably not a parent who’s going to care to monitor it much by remote app either. Is there enough insecurity around ‘what children under 13 really do online’, versus what I see or they tell me as a parent, that warrants 24/7 built-in surveillance software?

I can use safe settings without this app. I can use a device time limiting app without creating a Google account for my child.

If parents want to give children an email address, yes, this allows them to have a device linked Gmail account to which you as a parent, cannot access content. But wait a minute, what’s this. Google can?

Google can read their mails and provide them “personalised product features”. More detail is probably needed but this seems clear:

“Our automated systems analyze your child’s content (including emails) to provide your child personally relevant product features, such as customized search results and spam and malware detection.”

And what happens when the under 13s turn 13? It’s questionable that it is right for Google et al. to then be able draw on a pool of ready-made customers’ data in waiting. Free from COPPA ad regulation. Free from COPPA privacy regulation.

Google knows when the child reaches 13 (the set-up requires a child’s date of birth, their first and last name, and email address, to set up the account). And they will inform the child directly when they become eligible to sign up to a regular account free of parental oversight.

What a birthday gift. But is it packaged for the child or Google?

What’s in it for Google?

The parental disclosure begins,

“At Google, your trust is a priority for us.”

If it truly is, I’d suggest they revise their privacy policy entirely.

Google’s disclosure policy also makes parents read a lot before you fully understand the permissions this app gives to Google.

I do not believe Family Link gives parents adequate control of their children’s privacy at all nor does it protect children from predatory practices.

While “Google will not serve personalized ads to your child“, your child “will still see ads while using Google’s services.”

Google also tailors the Family Link apps that the child sees, (and begs you to buy) based on their data:

“(including combining personal information from one service with information, including personal information, from other Google services) to offer them tailored content, such as more relevant app recommendations or search results.”

Contextual advertising using “persistent identifiers” is permitted under COPPA, and is surely a fundamental flaw. It’s certainly one I wouldn’t want to see duplicated under GDPR. Serving up ads that are relevant to the content the child is using, doesn’t protect them from predatory ads at all.

Google captures geolocators and knows where a child is and builds up their behavioural and location patterns. Google, like other online companies, captures and uses what I’ve labelled ‘your synthesised self’; the mix of online and offline identity and behavioural data about a user. In this case, the who and where and what they are doing, are the synthesised selves of under 13 year old children.

These data are made more valuable by the connection to an adult with spending power.

The Google Privacy Policy’s description of how Google services generally use information applies to your child’s Google Account.

Google gains permission via the parent’s acceptance of the privacy policy, to pass personal data around to third parties and affiliates. An affiliate is an entity that belongs to the Google group of companies. Today, that’s a lot of companies.

Google’s ad network consists of Google services, like Search, YouTube and Gmail, as well as 2+ million non-Google websites and apps that partner with Google to show ads.

I also wonder if it will undo some of the previous pro-privacy features on any linked child’s YouTube account if Google links any logged in accounts across the Family Link and YouTube platforms.

Is this pseudo-safe use a good thing?

In practical terms, I’d suggest this app is likely to lull parents into a false sense of security. Privacy safeguarding is not the default set up.

It’s questionable that Google should adopt some sort of parenting role through an app. Parental remote controls via an app isn’t an appropriate way to regulate whether my under 13 year old is using their device, rather than sleeping.

It’s also got to raise questions about children’s autonomy at say, 12. Should I as a parent know exactly every website and app that my child visits? What does that do for parental-child trust and relations?

As for my own children I see no benefit compared with letting them have supervised access as I do already. That is without compromising my debit card details, or under a false sense of safeguarding. Their online time is based on age appropriate education and trust, and yes I have to manage their viewing time.

That said, if there are people who think parents cannot do that, is the app a step forward? I’m not convinced. It’s definitely of benefit to Google. But for families it feels more like a sop to adults who feel a duty towards safeguarding children, but aren’t sure how to do it.

Is this the best that Google can do by children?

In summary it seems to me that the Family Link app is a free gift from Google. (Well, free after the thirty cents to prove you’re a card-carrying adult.)

It gives parents three key tools: App approval (accept, pay, or block), Screen-time surveillance, and a remote Switch Off of child’s access.

In return, Google gets access to a valuable data set – a parent-child relationship with credit data attached – and can increase its potential targeted app sales. Yet Google can’t guarantee additional safeguarding, privacy, or benefits for the child while using it.

I think for families and child rights, it’s a false friend. None of these tools per se require a Google account. There are alternatives.

Children’s use of the Internet should not mean they are used and their personal data passed around or traded in hidden back room bidding by the Internet companies, with no hope of control.

There are other technical solutions to age verification and privacy too.

I’d ask, what else has Google considered and discarded?

Is this the best that a cutting edge technology giant can muster?

This isn’t designed to respect children’s rights as intended under COPPA or ready for GDPR, and it’s a shame they’re not trying.

If I were designing Family Link for children, it would collect no real identifiers. No voice. No locators. It would not permit others access to voice or images or need linked. It would keep children’s privacy intact, and enable them when older, to decide what they disclose. It would not target personalised apps/products at children at all.

GDPR requires active, informed parental consent for children’s online services. It must be revocable, personal data must collect the minimum necessary and be portable. Privacy policies must be clear to children. This, in terms of GDPR readiness, is nowhere near ‘it’.

Family Link needs to re-do their homework. And this isn’t a case of ‘please revise’.

Google is a multi-billion dollar company. If they want parental trust, and want to be GDPR and COPPA compliant, they should do the right thing.

When it comes to child rights, companies must do or do not. There is no try.

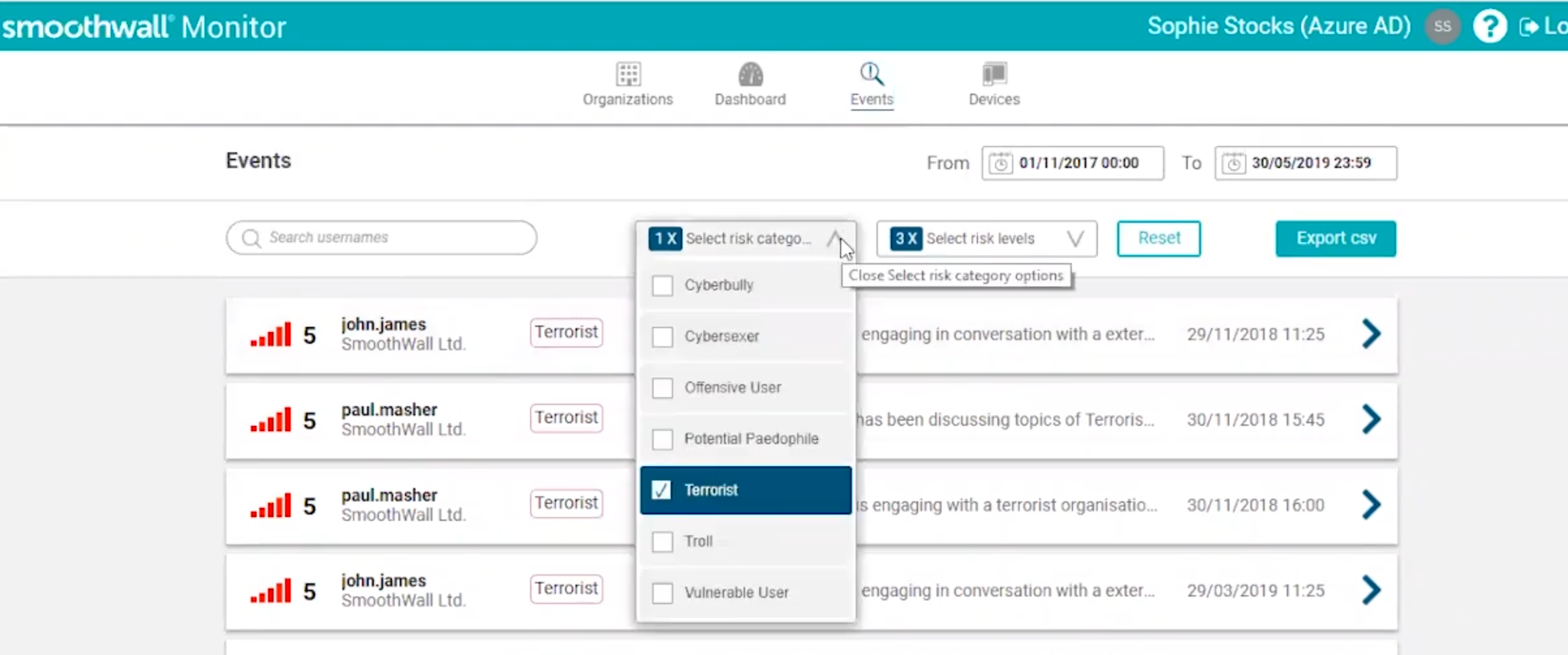

image source: ArsTechnica