Update received from Edmodo, VP Marketing & Adoption, June 1:

While everyone is focused on #WannaCry ransomware, it appears that a global edTech company has had a potential global data breach that few are yet talking about.

Edmodo is still claiming on its website it is, “The safest and easiest way for teachers to connect and collaborate with students, parents, and each other.” But is it true, and who verifies that safe is safe?

Edmodo data from 78 million users for sale

Matt Burgess wrote in VICE: “Education website Edmodo promises a way for “educators to connect and collaborate with students, parents, and each other”. However, 78 million of its customers have had their user account details stolen. Vice’s Motherboard reports that usernames, email addresses, and hashed passwords were taken from the service and have been put up for sale on the dark web for around $1,000 (£700).

“Data breach notification website LeakBase also has a copy of the data and provided it to Motherboard. According to LeakBase around 40 million of the accounts have email addresses connected to them. The company said it is aware of a “potential security incident” and is investigating.”

The Motherboard article by Joseph Cox, says it happened last month. What has been done since? Why is there no public information or notification about the breach on the company website?

Joseph doesn’t think profile photos are at risk, unless someone can log into an account. He was given usernames, email addresses, and hashed passwords, and as far as he knows, that was all that was stolen.

“The passwords have apparently been hashed with the robust bcrypt algorithm, and a string of random characters known as a salt, meaning hackers will have a much harder time obtaining user’s actual login credentials. Not all of the records include a user email address.”

Going further back, it looks like Edmodo’s weaknesses had already been identified 4 years ago. Did anything change?

So far I’ve been unable to find out from Edmodo directly. There is no telephone technical support. There is no human that can be reached dialling the headquarters telephone number.

Where’s the parental update?

No one has yet responded to say whether UK pupils and teachers’ data was among that reportedly stolen. (Update June 1, the company did respond with confirmation of UK users involved.)

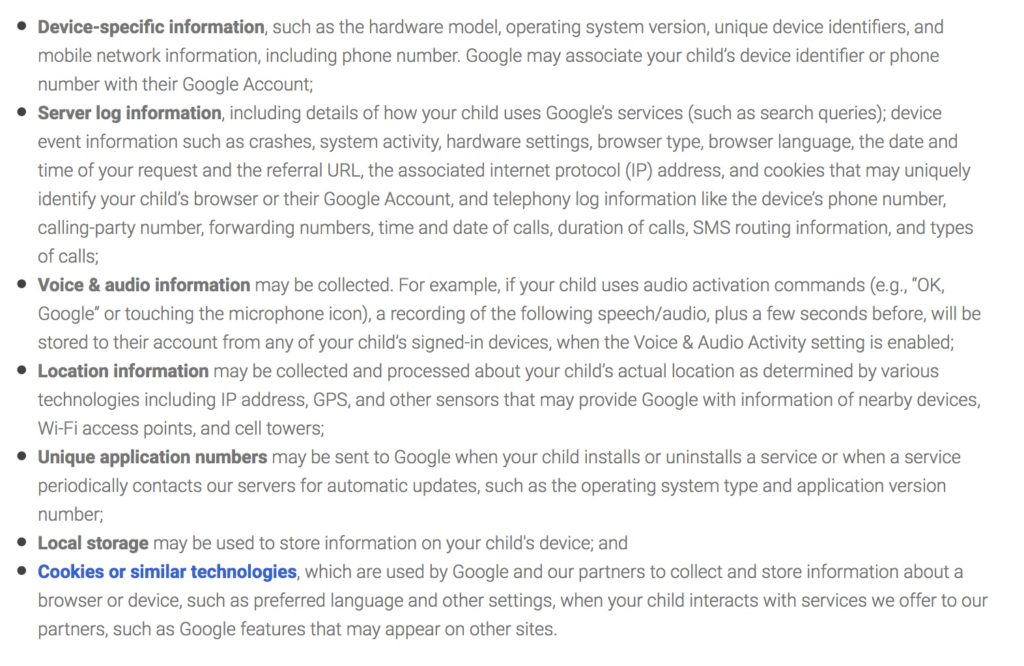

While there is no mention of the other data the site holds being in the breach, details are as yet sketchy, and Edmodo holds children’s data. Where is the company assurance what was and was not stolen?

As it’s a platform log on I would want to know when parents will be told exactly what was compromised and how details have been exposed. I would want clarification if this could potentially be a weakness for further breaches of other integrated systems, or not.

Are edTech and IoT toys fit for UK children?

In 2016, more than 727,000 UK children had their information compromised following a cyber attack on VTech, including images. These toys are sold as educational, even if targeted at an early age.

In Spring 2017, CloudPets, the maker of Internet of Things teddy bears, “smart toys” left more than two million voice recordings from children online without any security protections and exposing children’s personal details.

As yet UK ministers have declined our civil society recommendations to act and take steps on the public sector security of national pupil data or on the private security of Internet connected toys and things. The latter in line with Germany for example.

It is right that the approach is considered. The UK government must take these risks seriously in an evidence based and informed way, and act, not with knee jerk reactions. But it must act.

Two months after Germany banned the Cayla doll, we still had them for sale here.

Parents are often accused of being uninformed, but we must be able to expect that our products pass a minimum standard of tech and data security testing as part of pre-sale consumer safety testing.

Parents have a responsibility to educate themselves to a reasonable level of user knowledge. But the opportunities are limited when there’s no transparency. Much of the use of a child’s personal data and system data’s interaction with our online behaviour, in toys, things, and even plain websites remains hidden to most of us.

So too, the Edmodo privacy policy contained no mention of profiling or behavioural web tracking, for example. Only when this savvy parent spotted it was happening, it appears the company responded properly to fix it. Given strict COPPA rules it is perhaps unsurprising, though it shouldn’t have happened at all.

How will the uses of these smart toys, and edTech apps be made safe, and is the government going to update regulations to do so?

Are public sector policy, practice and people, fit for managing UK children’s data privacy needs?

While these private edTech companies used directly in schools can expose children to risk, so too does public data collected in schools, being handed out to commercial companies, by government departments. Our UK government does not model good practice.

Two years on, I’m still working on asking for fixes in basic national pupil data improvement. To make safe data policy, this is far too slow.

The Department for Education is still cagey about transparency, not telling schools it gives away national pupil data including to commercial companies without pupil or parental knowledge, and hides the Home Office use, now on a monthly basis, by not publishing it on a regular basis.

These uses of data are not safe, and expose children to potential greater theft, loss and selling of their personal data. It must change.

Whether the government hands out children’s data to commercial companies at national level and doesn’t tell schools, or staff in schools do it directly through in-class app registrations, it is often done without consent, and without any privacy impact assessment or due diligence up front. Some send data to the US or Australia. Schools still tell parents these are ‘required’ without any choice. But have they ensured that there is an equal and adequate level of data protection offered to personal data that they extract from the SIMs?

School staff and teachers manage, collect, administer personal data daily, including signing up children as users of web accounts with technology providers. Very often telling parents after the event, and with no choice. How can they and not put others at risk, if untrained in the basics of good data handling practices?

In our UK schools, just like the health system, the basics are still not being fixed or good practices on offer to staff. Teachers in the UK, get no data privacy or data protection training in their basic teacher training. That’s according to what I’ve been told so far from teacher trainers, CDP leaders, union members and teachers themselves,

Would you train fire fighters without ever letting them have hose practice?

Infrastructure is known to be exposed and under invested, but it’s not all about the tech. Security investment must also be in people.

Systemic failures seen this week revealed by WannaCry are not limited to the NHS. This from George Danezis could be, with few tweaks, copy pasted into education. So the question is not if, but when the same happens in education, unless it’s fixed.

“…from poor security standards in heath informatics industries; poor procurement processes in heath organizations; lack of liability on any of the software vendors (incl. Microsoft) for providing insecure software or devices; cost-cutting from the government on NHS cyber security with no constructive alternatives to mitigate risks; and finally the UK/US cyber-offense doctrine that inevitably leads to proliferation of cyber-weapons and their use on civilian critical infrastructures.” [Original post]