What can Matt Hancock learn from his app privacy flaws?

Note: since starting this blog, the privacy policy has been changed since what was live at 4.30 and the “last changed date” backdated on the version that is now live at 21.00. It shows the challenge I point out in 5:

It’s hard to trust privacy policy terms and conditions that are not strong and stable.

The Data Protection Bill about to pass through the House of Commons requires the Information Commissioner to prepare and issue codes of practice — which must be approved by the Secretary of State — before they can become statutory and enforced.

One of those new codes (clause 124) is about age-appropriate data protection design. Any provider of an Information Society Service — as outlined in GDPR Article 8, where a child’s data are collected on the legal basis of consent — must have regard for the code, if they target the site use at a child.

For 13 -18 year olds what changes might mean compared with current practices can be demonstrated by the Minister for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport’s new app, launched today.

This app is designed to be used by children 13+. Regardless that the terms say, [more aligned with US COPPA laws rather than GDPR] the app requires parental approval 13-18, it still needs to work for the child.

Apps could and should be used to open up what politics is about to children. Younger users are more likely to use an app than read a paper for example. But it must not cost them their freedoms. As others have written, this app has privacy flaws by design.

Children merit specific protection with regard to their personal data, as they may be less aware of the risks, consequences and safeguards concerned and their rights in relation to the processing of personal data. (GDPR Recital 38).

The flaw in the intent to protect by age, in the app, GDPR and UK Bill overall, is that understanding needed for consent is not dependent on age, but on capacity. The age-based model to protect the virtual child, is fundamentally flawed. It’s shortsighted, if well intentioned, but bad-by-design and does little to really protect children’s rights.

Future age verification for example; if it is to be helpful, not harm, or a nuisance like a new cookie law, must be “a narrow form of ‘identity assurance’ – where only one attribute (age) need be defined.” It must also respect Recital 57, and not mean a lazy data grab like GiffGaff’s.

On these 5 things this app fails to be age appropriate:

- Age appropriate participation, privacy, and consent design.

- Excessive personal data collection and permissions. (Article 25)

- The purposes of each data collected must be specified, explicit and not further processed for something incompatible with them. (Principle 2).

- The privacy policy terms and conditions must be easily understood by a child, and be accurate. (Recital 58)

- It’s hard to trust privacy policy terms and conditions that are not strong and stable. Among things that can change are terms on a free trial which should require active and affirmative action not continue the account forever, that may compel future costs. Any future changes, should also be age-appropriate of themselves, and in the way that consent is re-managed.

How much profiling does the app enable and what is it used for? The Article 29 WP recommends, “Because children represent a more vulnerable group of society, organisations should, in general, refrain from profiling them for marketing purposes.” What will this mean for any software that profile children’s meta-data to share with third parties, or commercial apps with in-app purchases, or “bait and switch” style models? As this app’s privacy policy refers to.

The Council of Europe 2016-21 Strategy on the Rights of the Child, recognises “provision for children in the digital environment ICT and digital media have added a new dimension to children’s right to education” exposing them to new risk, “privacy and data protection issues” and that “parents and teachers struggle to keep up with technological developments. ” [6. Growing up in a Digital World, Para 21]

Data protection by design really matters to get right for children and young people.

This is a commercially produced app and will only be used on a consent and optional basis.

This app shows how hard it can be for people buying tech from developers to understand and to trust what’s legal and appropriate.

For developers with changing laws and standards they need clarity and support to get it right. For parents and teachers they will need confidence to buy and let children use safe, quality technology.

Without relevant and trustworthy guidance, it’s nigh on impossible.

For any Minister in charge of the data protection rights of children, we need the technology they approve and put out for use by children, to be age-appropriate, and of the highest standards.

This app could and should be changed to meet them.

For children across the UK, more often using apps offers them no choice whether or not to use it. Many are required by schools that can make similar demands for their data and infringe their privacy rights for life. How much harder then, to protect their data security and rights, and keep track of their digital footprint where data goes.

If the Data protection Bill could have an ICO code of practice for children that goes beyond consent based data collection; to put clarity, consistency and confidence at the heart of good edTech for children, parents and schools, it would be warmly welcomed.

Here’s detailed examples what the Minister might change to make his app in line with GDPR, and age-appropriate for younger users.

1. Is the app age appropriate by design?

Unless otherwise specified in the App details on the applicable App Store, to use the App you must be 18 or older (or be 13 or older and have your parent or guardian’s consent).

Children over 13 can use the app, but this app needs parental consent. That’s different from GDPR– consent over and above the new laws as will apply in the UK from May. That age will vary across the EU. Inconsistent age policies are going to be hard to navigate.

Many of the things that matter to privacy, have not been included in the privacy policy (detailed below), but in the terms and conditions.

What else needs changed?

2. Personal data protection by design and default

Excessive personal data collection cannot be justified through a “consent” process, by agreeing to use the app. There must be data protection by design and default using the available technology. That includes data minimisation, and limited retention. (Article 25)

The apps powers are vast and collect far more personal data than is needed, and if you use it, even getting permission to listen to your mic. That is not data protection by design and default, which must implement data-protection principles, such as data minimisation.

If as has been suggested, in the newest version of android each permission is asked for at the point of use not on first install, that could be a serious challenge for parents who think they have reviewed and approved permissions pre-install (and fails beyond the scope of this app). An app only requires consent to install and can change the permissions behind the scenes at any time. It makes privacy and data protection by design even more important.

Here’s a copy of what the android Google library page says it can do. Once you click into “permissions” and scroll. This is excessive. “Matt Hancock” is designed to prevent your phone from sleeping, read and modify the contents of storage, and access your microphone.

Version 2.27 can access:

Location

- approximate location (network-based)

Phone

- read phone status and identity

Photos / Media / Files

- read the contents of your USB storage

- modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Storage

- read the contents of your USB storage

- modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Wi-Fi connection information

Device ID & call information

- read phone status and identity

Other

- control vibration

- manage document storage

- receive data from Internet

- view network connections

- full network access

- change your audio settings

- control vibration

- prevent device from sleeping

“Matt Hancock” knows where you live

The app makers – and Matt Hancock – should have no necessity to know where your phone is at all times, where it is regularly, or whose other phones you are near, unless you switch it off. That is excessive.

It’s not the same as saying “I’m a constituent”. It’s 24/7 surveillance.

The Ts&Cs say more.

It places the onus on the user to switch off location services — which you may expect for other apps such as your Strava run — rather than the developers take responsibility for your privacy by design. [Click image to see larger] [Full source policy].

[update since writing this post on February 1, the policy has been greatly added to]

It also collects ill-defined “technical information”. How should a 13 year old – or parent for that matter – know what these information are? Those data are the meta-data, the address and sender tags etc.

By using the App, you consent to us collecting and using technical information about your device and related information for the purpose of helping us to improve the App and provide any services to you.

As NSA General Counsel Stewart Baker has said, “metadata absolutely tells you everything about somebody’s life. General Michael Hayden, former director of the NSA and the CIA, has famously said, “We kill people based on metadata.”

If you use this app and “approve” the use, do you really know what the location services are tracking and how that data are used? For a young person, it is impossible to know, or see where their digital footprint has gone, or knowledge about them, have been used.

3. Specified, explicit, and necessary purposes

As a general principle, personal data must be only collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes. The purposes of these very broad data collection, are not clearly defined. That must be more specifically explained, especially given the data are so broad, and will include sensitive data. (Principle 2).

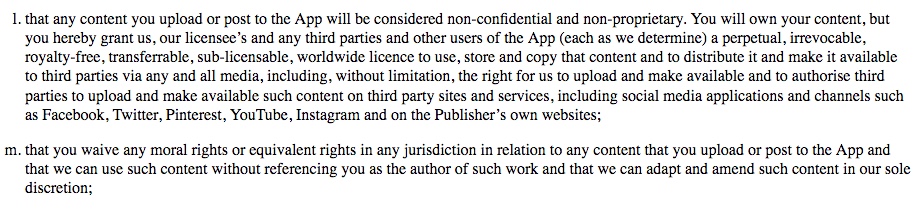

While the Minister has told the BBC that you maintain complete editorial control, the terms and conditions are quite different.

The app can use user photos, files, your audio and location data, and that once content is shared it is “a perpetual, irrevocable” permission to use and edit, this is not age-appropriate design for children who might accidentally click yes, or not appreciate what that may permit. Or later wish they could get that photo back. But now that photo is on social media potentially worldwide — “Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, YouTube, Instagram and on the Publisher’s own websites,” and the child’s rights to privacy and consent, are lost forever.

That’s not age appropriate and not in line with GDPR on rights to withdraw consent, to object or to restrict processing. In fact the terms, conflict with the app privacy policy which states those rights [see 4. App User Data Rights] Just writing “there may be valid reasons why we may be unable to do this” is poor practice and a CYA card.

4. Any privacy policy and app must do what it says

A privacy policy and terms and conditions must be easily understood by a child, [indeed any user] and be accurate.

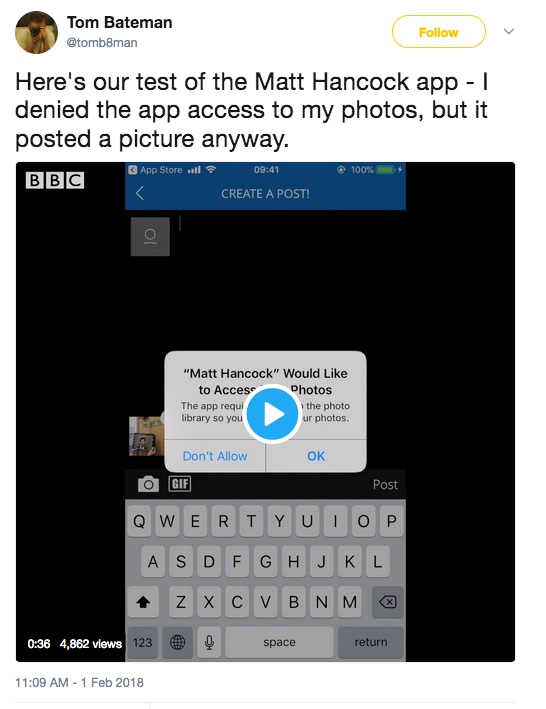

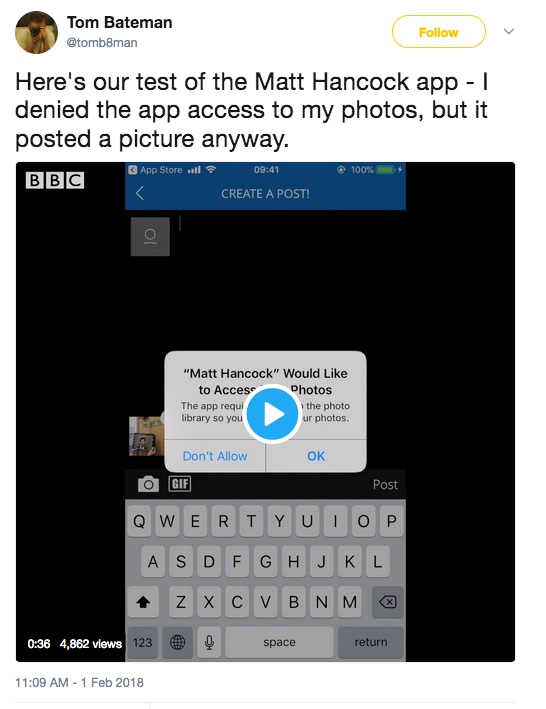

Journalists testing the app point out that even if the user clicks “don’t allow”, when prompted to permit access to the photo library, the user is allowed to post the photo anyway.

What does consent mean if you don’t know what you are consenting to? You’re not. GDPR requires that privacy policies are written in a way that their meaning can be understood by a child user (not only their parent). They need to be jargon-free and meaningful in “clear and plain language that the child can easily understand.” (Recital 58)

This privacy policy is not child-appropriate. It’s not even clear for adults.

5. What would age appropriate permissions for charging and other future changes look like?

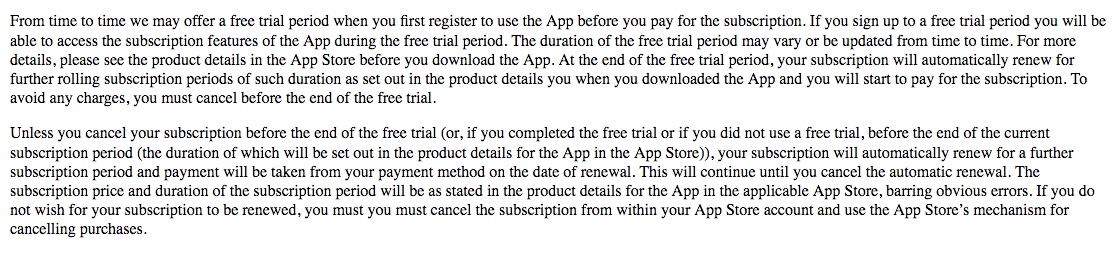

It should be clear to users if there may be up front or future costs, and there should be no assumption that agreeing once to pay for an app, means granting permission forever, without affirmative action.

Couching Bait-and-Switch, Hidden Costs

This is one of the flaws that the Matt Hancock app terms and conditions shares with many free education apps used in schools. At first, they’re free. You register, and you don’t even know when your child starts using the app, that it’s a free trial. But after a while, as determined by the developer, the app might not be free any more.

That’s not to say this is what the Matt Hancock app will do, in fact it would be very odd if it did. But odd then, that its privacy policy terms and conditions state it could.

The folly of boiler plate policy, or perhaps simply wanting to keep your options open?

Either way, it’s bad design for children– indeed any user — to agree to something that in fact, is meaningless because it could change at any time, and automatic renewals are convenient but who has not found they paid for an extra month of a newspaper or something else they intended to only use for a limited time? And to avoid any charges, you must cancel before the end of the free trial – but if you don’t know it’s free, that’s hard to do. More so for children.

From time to time we may offer a free trial period when you first register to use the App before you pay for the subscription.[…] To avoid any charges, you must cancel before the end of the free trial.

(And on the “For more details, please see the product details in the App Store before you download the App.” there aren’t any, in case you’re wondering).

What would age appropriate future changes be?

It should be clear to parents that what they consent to on behalf of a child, or if a child consents, at the time of install. What that means must empower them to better digital understanding and to stay in control, not allow the company to change the agreement, without the user’s clear and affirmative action.

One of the biggest flaws for parents in children using apps is that what they think they have reviewed, thought appropriate, and permitted, can change at any time, at the whim of the developer and as often as they like.

Notification “by updating the Effective Date listed above” is not any notification at all. And PS. they changed the policy and backdated it today from February 1, 2018, to July 2017. By 8 months. That’s odd.

The statements in this “changes” contradict one another. It’s a future dated get-out-of-jail-free-card for the developer and a transparency and oversight nightmare for parents. “Your continued use” is not clear, affirmative, and freely given consent, as demanded by GDPR.

Perhaps the kindest thing to say about this policy, and its poor privacy approach to rights and responsibilities, is that maybe the Minister did not read it. Which highlights the basic flaw in privacy policies in the first place. Data usage reports how your personal data have actually been used, versus what was promised, are of much greater value and meaning. That’s what children need in schools.