The news is full of the exam Regulator Ofqual right now, since yesterday’s A-Level results came out. In the outcry over the clear algorithmic injustice and inexplicable data-driven results, the data regulator, the Information Commissioner (ICO) remains silent.**

I have been told the Regulators worked together from early on in the process. So did this collaboration help or hinder the thousands of students and children whose rights the Regulators are supposed to work to protect?

I have my doubts, and here is why.

My child’s named national school records

On April 29, 2015 I wrote to the Department for Education (DfE) to ask for a copy of the data that they held about my eldest child in the National Pupil Database (NPD). A so-called Subject Access Request. The DfE responded on 12 May 2015 and refused, claiming an exemption, section 33(4) of the Data Protection Act 1998. In effect saying it was a research-only, not operational database.

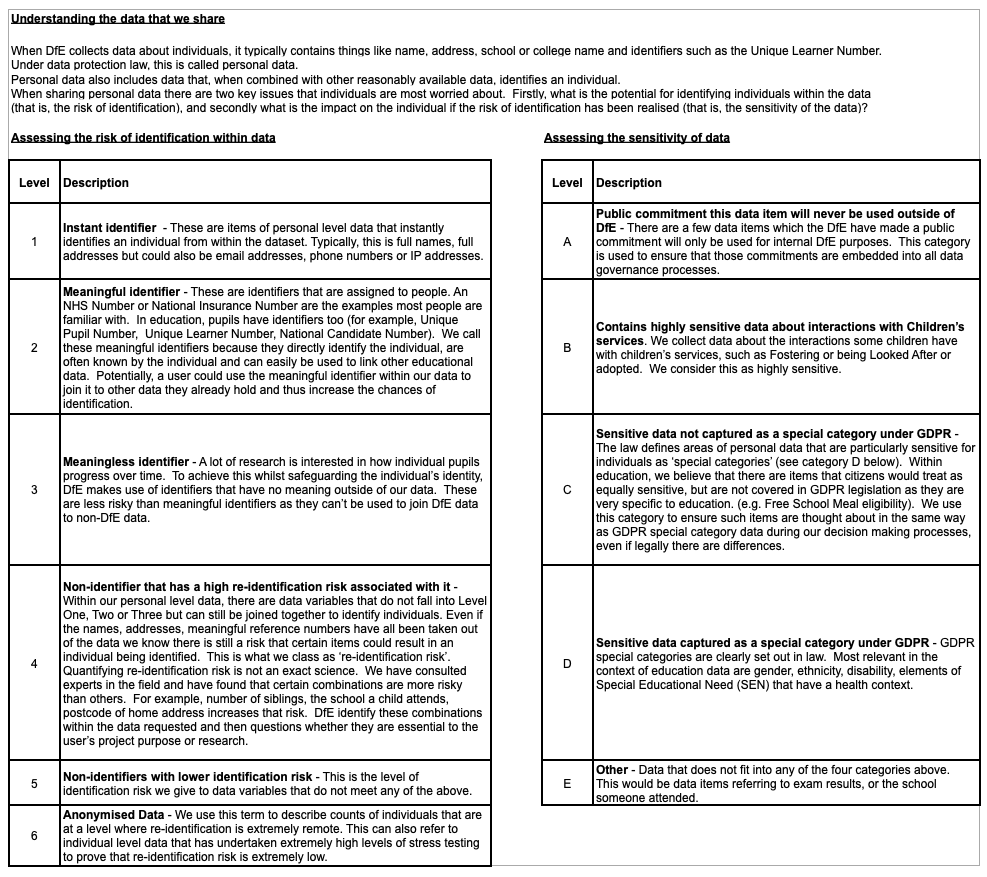

Despite being a parent of three children in state education in England, there was no clear information available to me what the government held in this database about my children. Building on what others in civil society had done before, I began research into what data was held. From where it was sourced and how often it was collected. Who the DfE gave the data to. For what purposes. How long it was kept. And I discovered a growing database of over 20 million individuals, of identifying and sensitive personal data, that is given away to commercial companies, charities, think tanks and press without suppression of small numbers and is never destroyed.

My children’s confidential records that I entrusted to school, and much more information they create that I never see, is given away for commercial purposes and I don’t get told which companies have it, why, or have any control over it? What about my Right to Object? I had imagined a school would only share statistics with third parties without parents’ knowledge or being asked. Well that’s nothing compared with what the Department does with it all next.

My 2015 complaint to the ICO

On October 6, 2015 I made a complaint to the Information Commissioner’s Office (the ICO). Admittedly, I was more naïve and less well informed than I am today, but the facts were clear.

Their response in April 2016, was to accept the DfE position, “at the stage at which this data forms part of its evidence base for certain purposes, it has been anonymised, aggregated and is statistical in nature. Therefore, for the purposes of the DPA, at the stage at which the DfE use NPD data for such purposes, it no longer constitutes personal data in any event.”

The ICO was “satisfied that the DfE met the criteria needed to rely on the exemption contained at section 33(4) of the DPA” and was justified in not fulfilling my request.

And “in relation to your concerns about the NPD and the adequacy of the privacy notice provided by the DfE, in broad terms, we consider it likely that this complies with the relevant data protection principles of the DPA.”

The ICO claimed “the processing does not cause any substantial damage or distress to individuals and that any results of the research/statistics are not made available in a form which identifies data subjects.”

The ICO kept its eyes wide shut

In secret in July 2015, the DfE had started to supply the Home Office with the matched personal details of children from the NPD, including home address. The Home Office requested this for purposes including to further the Hostile Environment. (15.1.2) which I only discovered in detail one year to the day after my ICO complaint, on October 6, 2016. The rest is public.

Had the ICO investigated the uses of national pupil data a year earlier in 2015-16, might it have prevented this ongoing gross misuse of children’s personal data and public and professional trust?

The ICO made no public statement despite widespread media coverage throughout 2016 and legal action on the expansion of the data, and intended use of children’s nationality and country-of-birth.

Identifying and sensitive not aggregated and statistical

Since 2012 the DfE has given away the sensitive and identifying personal confidential data of over 23 million people without their knowledge, in over 1600 unique requests, that are not anonymous.

In 2015 there was no Data Protection Impact Assessment. The Department had done zero audits of data users after sending them identifying pupil data. There was no ethics process or paperwork.

Today in England pupil data are less protected than across the rest of the UK. The NPD is being used as a source for creating a parent polling panel. Onward data sharing is opaque but some companies continue to receive named data and have done so for many years. It is a linked dataset with over 25 different collections, and includes highly sensitive children’s social care data, is frequently expanded, its content scope grows increasiningly sensitive, facilitates linkage to external datasets including children at risk and for policing, and has been used in criminology interventions which did harm and told children they were involved because they were “the worst kids.” Data has been given to journalists and a tutoring company. It has been sought after by Americans even if not (yet?) given to them.

Is the ICO a help or hindrance to protect children and young people’s data rights?

Five years ago the ICO told me the named records in the national pupil database was not personal data. Five years on, my legal team and I await a final regulatory response from the ICO that I hope will protect the human rights of my children, the millions currently in education in England whose data are actively collected, the millions aged 18-37 affected whose data were collected 1996-2012 but who don’t know, and those to come.

It has come at significant personal and legal costs and I welcome any support. It must be fixed. The question is whether the information rights Regulator is a help or hindrance?

If the ICO is working with organisations that have broken the law, or that plan dubious or unethical data processing, why is the Regulator collaborating to enable processing and showing them how to smooth off the edges rather than preventing harm and protecting rights? Can the ICO be both a friend and independent enforcer?

Why does it decline to take up complaints on behalf of parents that similarly affect millions of children in the UK and worldwide about companies that claim to use AI on their website but tell the ICO it’s just computing really. Or why has it given a green light on the reuse of religion and ethnicity from schools without consent, and tells the organisation they can later process it to make it anonymous, and keep all the personal data indefinitely?

I am angry at their inaction, but not as angry as thousands of children and their parents who know they have been let down by data-led decisions this month, that to them are inexplicable.

Thousands of children who are caught up in the algorithmic A-Level debacle and will be in next week’s GCSE processes believe they have been unfairly treated through the use of their personal data and have no clear route of redress. Where is the voice of the Regulator? What harm should they have prevented but didn’t through inaction?

What is the point of all the press and posturing on an Age Appropriate Code of Practice which goes beyond the scope of data protection, if the ICO cannot or will not enforce on its core remit or support the public it is supposed to serve?

Update: This post was published at midday on Friday Aust 14. In the late afternoon the ICO did post a short statement on the A-levels crisis, and also wrote to me regarding one of these cases via email.