Today Keir Starmer talked about us having more control in our lives. “Taking back control is a Labour argument”, he said. So let’s see it in education tech policy where parents told us in 2018, less than half felt they had sufficient control of their child’s digital footprint.

Not only has the UK lost control of which companies control large parts of the state education infrastructure and its delivery, the state is *literally* giving away control of our children’s lives recorded in identifiable data at national level, and since 2012 included giving it to journalists, think tanks, and companies.

Why it matters is less about the data per se, but what is done with it without our permission and how that affects our lives.

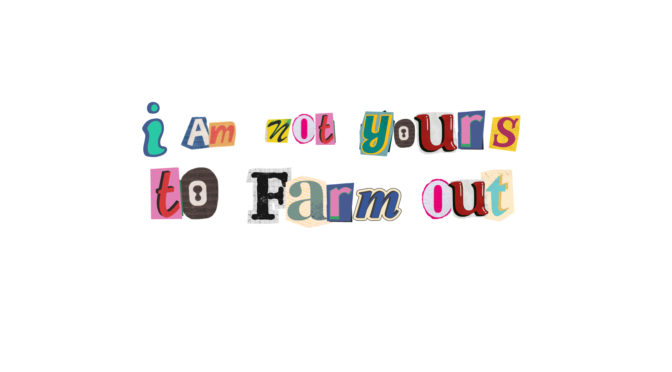

Politicians’ love affair with AI (undefined) seems to be as ardent as under the previous government. The State appears to have chosen to further commercialise children’s lives in data, having announced towards the end of the school summer holidays that the DfE and DSIT will give pupils’ assessment data to companies for AI product development. I get angry about this, because the data is badly misunderstood, and not a product to pass around but the stories of children’s lives in data, and that belongs to them to control.

Are we asking the right questions today about AI and education? In 2016 in a post for Nesta, Sam Smith foresaw the algorithmic fiasco that would happen in the summer of 2020 pointing out that exam-marking algorithms like any other decisions, have unevenly distributed consequences. What prevents that happening daily but behind closed doors and in closed systems? The answer is, nothing.

Both the adoption of AI in education and education about AI is unevenly distributed. Driven largely by commercial interests, some are co-opting teaching unions for access to the sector, others more cautious, have focused on the challenges of bias and discrimination and plagiarism. As I recently wrote in Schools Week, the influence of corporate donors and their interests in shaping public sector procurement, such as the Tony Blair Institute’s backing by Oracle owner Larry Ellison, therefore demands scrutiny.

Should society allow its public sector systems and laws to be shaped primarily to suit companies? The users of the systems are shaped by how those companies work, so who keeps the balance in check?

In a 2021 reflection here on World Children’s Day, I asked the question, Man or Machine, who shapes my child? Three years later, I am still concerned about the failure to recognize and address the question of redistribution of not only pupils’ agency but teachers’ authority; from individuals to companies (pupils and the teacher don’t decide what is ‘right’ you do next, the ‘computer’ does). From public interest institutions to companies (company X determines the curriculum content of what the computer does and how, not the school). And from State to companies (accountability for outcomes falls through the gap in outsourcing activity to the AI company).

Why it matters, is that these choices do not only influence how we are teaching and learning, but how children feel about it and develop.

The human response to surveillance (and that is what much of AI relies on, massive data-veillance and dashboards) is a result of the chilling effect of being ‘watched‘ by known or unknown persons behind the monitoring. We modify our behaviours to be compliant to their expectations. We try not to stand out from the norm, or to protect ourselves from resulting effects.

The second reason we modify our behaviours is to be compliant with the machine itself. Thanks to the lack of a responsible human in the interaction mediated by the AI tool, we are forced to change what we do to comply with what the machine can manage. How AI is changing human behaviour is not confined to where we walk, meet, play and are overseen in out- or indoor spaces. It is in how we respond to it, and ultimately, how we think.

In the simplest examples, using voice assistants shapes how children speak, and in prompting generative AI applications, we can see how we are forced to adapt how we think to put the questions best suited to getting the output we want. We are changing how we behave to suit machines. How we change behaviour is therefore determined by the design of the company behind the product.

There is limited public debate yet on the effects of this for education, on how children act, interact, and think using machines, and no consensus in the UK education sector whether it is desirable to introduce these companies and their steering that bring changes in teaching and learning and to the future of society, as a result.

And since then in 2021, I would go further. The neo-liberal approach to education and its emphasis on the efficiency of human capital and productivity, on individualism and personalisation, all about producing ‘labour market value’, and measurable outcomes, is commonly at the core of AI in teaching and learning platforms.

Many tools dehumanise children into data dashboards, rank and spank their behaviours and achivements, punish outliers and praise norms, and expect nothing but strict adherence to rules (sometimes incorrect ones, like mistakes in maths apps). As some companies have expressly said, the purpose of this is to normalise such behaviours ready to be employees of the future, and the reason their tools are free is to normalise their adoption for life.

AI by the normalisation of values built-in by design to tools, is even seen by some as encouraging fascistic solutions to social problems.

But the purpose of education is not only about individual skills and producing human capital to exploit. Education is a vital gateway to rights and the protection of a democratic society. Education must not only be about skills as an economic driver when talking about AI and learners in terms of human capital, but include rights, championing the development of a child’s personality to their fullest potential, and intercultural understanding, digital citizenship on dis-/misinformation, discrimination and the promotion and protection of democracy and the natural world. “It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.”

Peter Kyle, the UK DSIT’s Secretary of State said last week, that, “more than anything else, it is growth that will shape those young people’s future.” But what will be used to power all this growth in AI, at what environmental and social costs, and will we get a say?

Don’t forget, in this project announcement the Minister said, “This is the first of many projects that will transform how we see and use public sector data.” That’s our data, about us. And when it comes to schools, that’s not only the millions of learners who’ve left already but who are school children today. Are we really going to accept turning them into data fodder for AI without a fight? As Michael Rosen summed up so perfectly in 2018, “First they said they needed data about the children to find out what they’re learning… then the children became data.” If this is to become the new normal, where is the mechanism for us to object? And why this, now, in such a hurry?

Purpose limitation should also prevent retrospective reuse of learners’ records and data, but it hasn’t so far on general identifying and sensitive data distribution from the NPD at national level or from edTech in schools. The project details, scant as they are, suggest parents were asked for consent in this particular pilot, but the Faculty AI notice seems legally weak for schools, and when it comes to using pupil data for building into AI products the question is whether consent can ever be valid — since it cannot be withdrawn once given, and the nature of being ‘freely given’ is affected by the power imbalance.

So far there is no field to record an opt out in any schools’ Information Management Systems though many discussions suggest it would be relatively straightforward to make it happen. However it’s important to note their own DSIT public engagement work on that project says that opt-in is what those parents told the government they would expect. And there is a decade of UK public engagement on data telling government opt-in is what we want.

The regulator has been silent so far on the DSIT/DfE announcement despite lack of fair processing and failures on Articles 12, 13 and 14 of the GDPR being one of the key findings in its 2020 DfE audit. I can use a website to find children’s school photos, scraped without our permission. What about our school records?

Will the government consult before commercialising children’s lives in data to feed AI companies and ‘the economy’ or any of the other “many projects that will transform how we see and use public sector data“? How is it different from the existing ONS, ADR, or SAIL databank access points and processes? Will the government evaluate the impact on child development, behaviour or mental health of increasing surveillance in schools? Will MPs get an opt-in or even -out, of the commercialisation of their own school records?

I don’t know about ‘Britain belongs to us‘, but my own data should.