The National Data Strategy is not about “the data”. People need to stop thinking of data only as abstract information, or even as personal data when it comes to national policy. Administrative data is the knowledge about the workings of the interactions between the public and the State and about us as people. It is the story of selected life events. To the State it is business intelligence. What resources are used, where, by whom and who costs The Treasury how much? How any government is permitted to govern that, shapes our relationship with the State and the nature of the governance we get of people, of public services. How much power we cede to the State or retain at national, local, and individual levels over our communities and our lives matters. Any change in National Data Strategy is about the rewiring of state power, and we need to understand its terms and conditions very, very carefully.

What government wants

“It’s not to say we don’t see privacy and data protection as not important,” said Phil Earl, Deputy Director at DCMS, in the panel discussion hosted by techUK as part of Birmingham Tech Week, exploring the UK Government’s recently released National Data Strategy.

I sighed so loudly I was glad to be on mute. The first of many big watch outs for the messaging around the National Data Strategy was already touted in the text, as “the high watermark of data use set during the pandemic.” In response to COVID “a few of the perceived barriers seem to have melted away,” said Earl, and saw this reduced state of data protections is desirable beyond the pandemic. “Can we maintain that level of collaboration and willingness to share data?” he asked.

Data protection laws are at their heart protections for people, not data, and if any government is seeking to reduce those protections for people we should pay attention to messaging very carefully.

This positioning fails to recognise that data protection law is more permissive in exceptional circumstances such as pandemics, with a recognition by default that the tests in law of necessity and proportionality are different from usual, and are time bound to the pandemic.

“What’s the equivalent? How do we empower people to feel that that greater good [felt in the pandemic] outweighs their legitimate concerns about data being shared,” he said.” The whole trust thing is something that must be constantly maintained,” but you may hear between the lines, ‘preferably on our [government] terms.’

The idea that the public is ignorant about data, is often repeated and still wrong. The same old mantras resurfaced. If people can make more informed decisions, understand “the benefits”, then the government can influence their judgments, trusting us to “make the decisions that we want them to make [to agree to data re-use].”

If *this* is the government set course (again), then watch out.

What people want

In fact when asked, the majority of people both who are willing and less willing to have data about them reused, generally want the same things. Safeguards, opt in to re use, restricted distribution, and protections for redress and against misuse strengthened in legislation.

Read Doteveryone’s public attitudes work. Or the Ipsos MORI polls or work by Wellcome. (see below). Or even the care.data summaries.

The red lines in the “Dialogues on Data” report from workshops carried out across different regions of the UK for the 2013 ADRN (about reuse of deidentified linked public admin datasets by qualified researchers in safe settings), remain valid today, in particular with relation to:

-

Creating large databases containing many variables/data from a large number of public sector sources

-

Allowing administrative data to be linked with business data

-

Linking of passively collected administrative data, in particular geo-location data

“All of the above were seen as having potential privacy implications or allowing the possibility of reidentification of individuals within datasets. The other ‘red-line’ for some participants was allowing researchers for private companies to access data, either to deliver a public service or in order to make profit. Trust in private companies’ motivations were low.”

The BT spokesperson on the panel, went on to say that their own survey showed 85% of people say their data is important to them, and 75% believe they have too little control.

Mr. Earl was absolutely correct in saying it puts the onus on government to be transparent and show how data will be used. But we hear *nothing* about concrete plans to deliver that. What does that look like? Saying it three times out loud, doesn’t make it real.

What government does

Government needs to embrace the fact it can only get data right, if it does the right thing. That includes upholding the law. This includes examining its own purposes and practice.

The Department for Education has been giving away 15 million people’s personal confidential data since 2012 and never told them. They knew this. They chose to ignore it. And on top of that, didn’t inform people who were in school since then, that Mr Gove changed the law. So now over 21 million people’s pupil records are being given away to comapnies and other third parties, for use in ways we do not expect, and is misused too. In 2015, more secret data sharing began, with the Home Office. And another pilot in 2018 with the DWP. And in 2019, sharing with the police.

Promises on government data policy transparency right now are worth less than zero. What matters now is government actions. Trust will be based on what you do, not what you say. Is the government trustworthy?

After the summary findings published by the ICO of their compulsory audit of the Department for Education, the question now is what will the Department and government do to address the 139 recommendations for improvement, with over 60% classified as urgent or high priority. Is the government intentional about change?

What will government do?

So I had a question for the panel: Is the government serious about its point in the strategy, 7.1.2 “Our data regime should empower individuals and groups to control and understand how their data is used.”

I didn’t get an answer.

I want to know if the government is prepared to build the necessary infrastructure to enable that understanding and control?

- Enhance and build the physical infrastructure:

-

- access to personal reports what data is held and how it is used.

- management controls and communications over reuse [opt-in to meet the necessary permissions of legitimate interests or consent as lawful basis for further data processing, conditions for sensitive data processing, or at very least opt-out to respect objections].

- secure systems (not just excel, and WannaCry resistant)

-

- Enable the necessary transparency tools and create demonstrable accountability through registers of algorithms and data sharing with oversight functions and routes for redress.

- Empower staff with the necessary human skills at all levels in the public sector on the laws around data that do not just consist of a sharepoint on GDPR — what about privacy law, communications law, equality and discrimination laws among others?

- Empower the public with the controls they want to have their rights respected.

- Examine toxic policy that drives bad data collection and re-use.

Public admin data is all about people

Coming soon is the publication of an Integrated Review, we were told, how ‘data and security’ and other joined up issues will feature.

A risk of this conflation is seeing the national data strategy as another dry review about data as ‘a thing’, or its management.

It should be about people. The people who our public admin data are about. The people that want access to it. The people making the policy decisions. And its human infrastructure. The controls on power about purposes of the data reuse, data governance is all about the roles and responsibilties of people and the laws that oversee them and require human accountability.

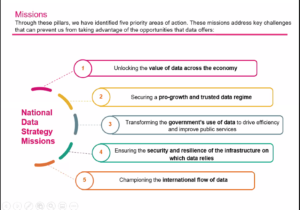

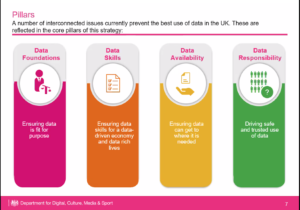

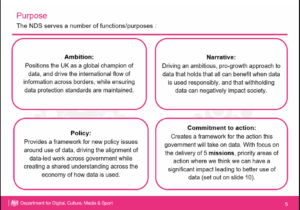

These NDS strategy missions, and pillars and aims are all about “the data”.

For a national data strategy to be realised and to thrive in all of our wide ranging societal ‘data’ interests, it cannot be all about data as a commodity. Or all about government wants. Or seen through the lens only of research. Allow that, and they divide and conquer. It must be founded on building a social contract between government and the public in a digital environment, and setting the expectations of these multi-purpose relationships, at national, and local levels.

For a forward thinking data strategy truly building something in the long term public interest, it is about understanding ‘wider public need‘. The purpose of ‘the data’ and its strategy, is as much about the purpose of government behind it. Data is personal. But when used to make decisions it also business intelligence. How does the government make the business of governing work, through data?

Any national data strategy does not sit in a vacuum of other policy and public experience of government either. If Manchester‘s second lockdown funding treatment is seen as the expectations of how local needs get trumped by national wants, and people’s wishes will be steam rollered, then a national approach will not win support. A long list of bad government engagement over recent months, is a poor foundation and you don’t fix that by talking about “the benefits”.

Will government listen?

Edgenuity, the U.S. based school assessment system using AI for marking, made the news this summer, when parents found it could be gamed by simply packing essays with all the right keywords, but respondents didn’t need to make sense or give accurate answers. To be received well and get a good grade, they were expected simply to tell the system the words ‘it wanted to hear’.

“If the teachers were looking at the responses, they didn’t care,” one student said.

Will the government actually look at responses to the National Data Strategy and care about getting it right? Not just care about getting what they want? Or about what commercial actors will do with it?

Government wanted to and changed the law on education admin data in 2012 and got it wrong. Education data alone is a sin bin of bad habits and complete lack of public and professional engagement, before even starting to address data quality and accuracy and backwards looking policy built on bad historic data.

“The Commercial department do not have appropriate controls in place to protect personal data being processed on behalf of the DfE by data processors.” (ICO audit of the DfE , 2020)

Gambling companies ended up misusing learner records.

Government wanted data from one Department to be collected for the purposes of another and got it wrong. People boycotted the collection until it was killed off.

Government changed the law on Higher Education in 2017 and got it wrong. Now third parties pass around named equality monitoring records like religion, sexual orientation, and disability and it is stored forever on named national pupil records. The Department for Education (DfE) now holds sexual orientation data on almost 3.2 million, and religious belief data on 3.7 million people.

What could possibly go wrong?

If the current path is any indicator, this government is little interested in local power, or people, and certainly not in our human rights. They are interested in centralised power. We should be very cautious about giving that all away to the State on its own terms.

The national data strategy consultation is open for submissions until

Samples of public engagement on data reuse

- RAENG (2010) On children and health data Privacy and Prejudice: young people’s views on the development and use of Electronic Patient Records (911.18 KB). They are very clear about wanting to keep their medical details under their own control and away from the ‘wrong hands’ which includes the potential employers, commercial companies and parents.

- ADRN (2013) on *deidentified* personal data including red lines on creating mega databases and commercial re-use esrc.ukri.org/public-engagem

- The Royal Statistical Society (RSS) (2014) https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/new-research-finds-data-trust-deficit-lessons-policymakers The data trust deficit with lessons for policy makers

- UCAS applicant survey with 37,000 respondents (2015) https://www.ucas.com/corporate/news-and-key-documents/news/37000-students-respond-ucas%E2%80%99-applicant-data-survey A majority of UCAS applicants (64%) agree that sharing personal data can benefit them and support research into university admissions, but they want to stay firmly in control, with nine out of ten saying they should be asked first.

- Wellcome Trust/ Ipsos MORI (2017) The One-Way Mirror: Public attitudes to commercial access to health data https://wellcome.figshare.com/articles/journal%20contribution/The_One-Way_Mirror_Public_attitudes_to_commercial_access_to_health_data/5616448/1

- defenddigitalme (2018) Parents’ poll ‘Only half of parents think they have enough control of children’s digital footprint’. defenddigitalme.org/2018/03/only-h

- DotEveryone(2018-20) doteveryone.org.uk/project/people Their public attitudes report found that although people’s digital understanding has grown, that’s not helping them to shape their online experiences in line with their own wishes.

- LSE (2019-20) Children’s privacy online lse.ac.uk/my-privacy-uk