The Fabian Women, Glass Ceiling not Glass Slipper event, asked last week:

Is Education preparing us for the jobs of the future?

The panel talked about changing social and political realities. We considered the effects on employment. We began discussion how those changes should feed into education policy and practice today. It is discussion that should be had by the public. So far, almost a year after the Referendum, the UK government is yet to say what post-Brexit Britain might look like. Without a vision, any mandate for the unknown, if voted for on June 9th, will be meaningless.

What was talked about and what should be a public debate:

- What jobs will be needed in the future?

- Post Brexit, what skills will we need in the UK?

- How can the education system adapt and improve to help future generations develop skills in this ever changing landscape?

- How do we ensure women [and anyone else] are not left behind?

Brexit is the biggest change management project I may never see.

As the State continues making and remaking laws, reforming education, and starts exiting the EU, all in parallel, technology and commercial companies won’t wait to see what the post-Brexit Britain will look like. In our state’s absence of vision, companies are shaping policy and ‘re-writing’ their own version of regulations. What implications could this have for long term public good?

What will be needed in the UK future?

A couple of sentences from Alan Penn have stuck with me all week. Loosely quoted, we’re seeing cultural identity shift across the country, due to the change of our available employment types. Traditional industries once ran in a family, with a strong sense of heritage. New jobs don’t offer that. It leaves a gap we cannot fill with “I’m a call centre worker”. And this change is unevenly felt.

There is no tangible public plan in the Digital Strategy for dealing with that change in the coming 10 to 20 years employment market and what it means tied into education. It matters when many believe, as do these authors in American Scientific, “around half of today’s jobs will be threatened by algorithms. 40% of today’s top 500 companies will have vanished in a decade.”

So what needs thought?

- Analysis of what that regional jobs market might look like, should be a public part of the Brexit debate and these elections →

We need to see those goals, to ensure policy can be planned for education and benchmark its progress towards achieving its aims - Brexit and technology will disproportionately affect different segments of the jobs market and therefore the population by age, by region, by socio-economic factors →

Education policy must therefore address aspects of skills looking to the future towards employment in that new environment, so that we make the most of opportunities, and mitigate the harms. - Brexit and technology will disproportionately affect communities → What will be done to prevent social collapse in regions hardest hit by change?

Where are we starting from today?

Before we can understand the impact of change, we need to understand what the present looks like. I cannot find a map of what the English education system looks like. No one I ask seems to have one or have a firm grasp across the sector, of how and where all the parts of England’s education system fit together, or their oversight and accountability. Everyone has an idea, but no one can join the dots. If you have, please let me know.

Nothing is constant in education like change; in laws, policy and its effects in practice, so I shall start there.

1. Legislation

In retrospect it was a fatal flaw, missed in post-Referendum battles of who wrote what on the side of a bus, that no one did an assessment of education [and indeed other] ‘legislation in progress’. There should have been recommendations made on scrapping inappropriate government bills in entirety or in parts. New laws are now being enacted, rushed through in wash up, that are geared to our old status quo, and we risk basing policy only on what we know from the past, because on that, we have data.

In the timeframe that Brexit will become tangible, we will feel the effects of the greatest shake up of Higher Education in 25 years. Parts of the Higher Education and Research Act, and Technical and Further Education Act are unsuited to the new order post-Brexit.

What it will do: The new HE law encourages competition between institutions, and the TFE Act centred in large part on how to manage insolvency.

What it should do: Policy needs to promote open, collaborative networks if within a now reduced research and academic circle, scholarly communities are to thrive.

If nothing changes, we will see harm to these teaching institutions and people in them. The stance on counting foreign students in total migrant numbers, to take an example, is singularly pointless.

Even the Royal Society report on Machine Learning noted the UK approach to immigration as a potential harm to prosperity.

Local authorities cannot legally build schools under their authority today, even if needed. They must be free schools. This model has seen high turnover and closures, a rather instable model.

Legislation has recently not only meant restructure, but repurposing of what education [authorities] is expected to offer.

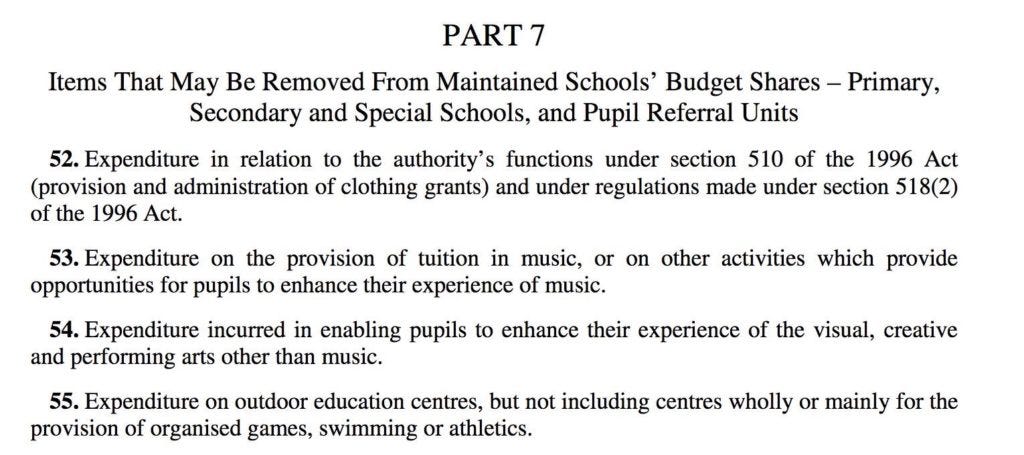

A new Statutory Instrument — The School and Early Years Finance (England) Regulations 2017 — makes music, arts and playgrounds items; ‘That may be removed from maintained schools’ budget shares’.

How will this withdrawal of provision affect skills starting from the Early Years throughout young people’s education?

2. Policy

Education policy if it continues along the grammar school path, will divide communities into ‘passed’ and the ‘unselected’. A side effect of selective schooling— a feature or a bug dependent on your point of view — is socio-economic engineering. It builds class walls in the classroom, while others, like Fabian Women, say we should be breaking through glass ceilings. Current policy in a wider sense, is creating an environment that is hostile to human integration. It creates division across the entire education system for children aged 2–19.

The curriculum is narrowing, according to staff I’ve spoken to recently, as a result of measurement focus on Progress 8, and due to funding constraints.

What effect will this have on analysis of knowledge, discernment, how to assess when computers have made a mistake or supplied misinformation, and how to apply wisdom? Skills that today still distinguish human from machine learning.

What narrowing the curriculum does: Students have fewer opportunities to discover their skill set, limiting opportunities for developing social skills and cultural development, and their development as rounded, happy, human beings.

What we could do: Promote long term love of learning in-and-outside school and in communities. Reinvest in the arts, music and play, which support mental and physical health and create a culture in which people like to live as well as work. Library and community centres funding must be re-prioritised, ensuring inclusion and provision outside school for all abilities.

Austerity builds barriers of access to opportunity and skills. Children who cannot afford to, are excluded from extra curricular classes. We already divide our children through private and state education, into those who have better facilities and funding to enjoy and explore a fully rounded education, and those whose funding will not stretch much beyond the bare curriculum. For SEN children, that has already been stripped back further.

All the accepted current evidence says selective schooling limits social mobility and limits choice. Talk of evidence based profession is hard to square with passion for grammars, an against-the-evidence based policy.

Existing barriers are likely to become entrenched in twenty years. What does it do to society, if we are divided in our communities by money, or gender, or race, and feel disempowered as individuals? Are we less responsible for our actions if there’s nothing we can do about it? If others have more money, more power than us, others have more control over our lives, and “no matter what we do, we won’t pass the 11 plus”?

Without joined-up scrutiny of these policy effects across the board, we risk embedding these barriers into future planning. Today’s data are used to train “how the system should work”. If current data are what applicants in 5 years will base future expectations on, will their decisions be objective and will in-built bias be transparent?

3. Sociological effects of legislation.

It’s not only institutions that will lose autonomy in the Higher Education and Research Act.

At present, the risk to the autonomy of science and research is theoretical — but the implications for academic freedom are troubling. [Nature 538, 5 (06 October 2016)]

The Secretary of State for Education now also has new Powers of Information about individual applicants and students. Combined with the Digital Economy Act, the law can ride roughshod over students’ autonomy and consent choices. Today they can opt out of UCAS automatically sharing their personal data with the Student Loans Company for example. Thanks to these new powers, and combined with the Digital Economy Act, that’s gone.

The Act further includes the intention to make institutions release more data about course intake and results under the banner of ‘transparency’. Part of the aim is indisputably positive, to expose discrimination and inequality of all kinds. It also aims to make the £ cost-benefit return “clearer” to applicants — by showing what exams you need to get in, what you come out with, and then by joining all that personal data to the longitudinal school record, tax and welfare data, you see what the return is on your student loan. The government can also then see what your education ‘cost or benefit’ the Treasury. It is all of course much more nuanced than that, but that’s the very simplified gist.

This ‘destinations data’ is going to be a dataset we hear ever more about and has the potential to influence education policy from age 2.

Aside from the issue of personal data disclosiveness when published by institutions — we already know of individuals who could spot themselves in a current published dataset — I worry that this direction using data for ‘advice’ is unhelpful. What if we’re looking at the wrong data upon which to base future decisions? The past doesn’t take account of Brexit or enable applicants to do so.

Researchers [and applicants, the year before they apply or start a course] will be looking at what *was* — predicted and achieved qualifying grades, make up of the class, course results, first job earnings — what was for other people, is at least 5 years old by the time it’s looked at it. Five years is a long time out of date.

4. Change

Teachers and schools have long since reached saturation point in the last 5 years to handle change. Reform has been drastic, in structures, curriculum, and ongoing in funding. There is no ongoing teacher training, and lack of CPD take up, is exacerbated by underfunding.

Teachers are fed up with change. They want stability. But contrary to the current “strong and stable” message, reality is that ahead we will get anything but, and must instead manage change if we are to thrive. Politically, we will see backlash when ‘stable’ is undeliverable.

But Teaching has not seen ‘stable’ for some time. Teachers are asking for fewer children, and more cash in the classroom. Unions talk of a focus on learning, not testing, to drive school standards. If the planned restructuring of funding happens, how will it affect staff retention?

We know schools are already reducing staff. How will this affect employment, adult and children’s skill development, their ambition, and society and economy?

Where could legislation and policy look ahead?

- What are the big Brexit targets and barriers and when do we expect them?

- How is the fall out from underfunding and reduction of teaching staff expected to affect skills provision?

- State education policy is increasingly hands-off. What is the incentive for local schools or MATs to look much beyond the short term?

- How do local decisions ensure education is preparing their community, but also considering society, health and (elderly) social care, Post-Brexit readiness and women’s economic empowerment?

- How does our ageing population shift in the same time frame?

How can the education system adapt?

We need to talk more about other changes in the system in parallel to Brexit; join the dots, plus the potential positive and harmful effects of technology.

Gender here too plays a role, as does mitigating discrimination of all kinds, confirmation bias, and even in the tech itself, whether AI for example, is going to be better than us at decision-making, if we teach AI to be biased.

Dr Lisa Maria Mueller talked about the effects and influence of age, setting and language factors on what skills we will need, and employment. While there are certain skills sets that computers are and will be better at than people, she argued society also needs to continue to cultivate human skills in cultural sensitivities, empathy, and understanding. We all nodded. But how?

To develop all these human skills is going to take investment. Investment in the humans that teach us. Bennie Kara, Assistant Headteacher in London, spoke about school cuts and how they will affect children’s futures.

The future of England’s education must be geared to a world in which knowledge and facts are ubiquitous, and readily available online than at any other time. And access to learning must be inclusive. That means including SEN and low income families, the unskilled, everyone. As we become more internationally remote, we must put safeguards in place if we to support thriving communities.

Policy and legislation must also preserve and respect human dignity in a changing work environment, and review not only what work is on offer, but *how*; the kinds of contracts and jobs available.

Where might practice need to adapt now?

- Re-consider curriculum content with its focus on facts. Will success risk being measured based on out of date knowledge, and a measure of recall? Are these skills in growing or dwindling need?

- Knowledge focus must place value on analysis, discernment, and application of facts that computers will learn and recall better than us. Much of that learning happens outside school.

- Opportunities have been cut, together with funding. We need communities brought back together, if they are not to collapse. Funding centres of local learning, restoring libraries and community centres will be essential to local skill development.

What is missing?

Although Sarah Waite spoke (in a suitably Purdah appropriate tone), about the importance of basic skills in the future labour market we didn’t get to talking about education preparing us for the lack of jobs of the future and what that changed labour market will look like.

What skills will *not* be needed? Who decides? If left to companies’ sponsor led steer in academies, what effects will we see in society?

Discussions of a future education model and technology seem to share a common theme: people seem reduced in making autonomous choices. But they share no positive vision.

- Technology should empower us, but it seems to empower the State and diminish citizens’ autonomy in many of today’s policies, and in future scenarios especially around the use of personal data and Digital Economy.

- Technology should enable greater collaboration, but current tech in education policy is focused too little on use on children’s own terms, and too heavily on top-down monitoring: of scoring, screen time, search terms. Further restrictions by Age Verification are coming, and may access and reduce participation in online services if not done well.

- Infrastructure weakness is letting down the skill training: University Technical Colleges (UTCs) are not popular and failing to fill places. There is lack of an overarching area wide strategic plan for pupils in which UTCS play a part. Local Authorities played an important part in regional planning which needs restored to ensure joined up local thinking.

How do we ensure women are not left behind?

The final question of the evening asked how women will be affected by Brexit and changing job market. Part of the risks overall, the panel concluded, is related to [lack of] equal-pay. But where are the assessments of the gendered effects in the UK of:

- community structural change and intra-family support and effect on demand for social care

- tech solutions in response to lack of human interaction and staffing shortages including robots in the home and telecare

- the disproportionate drop out of work, due to unpaid care roles, and difficulty getting back in after a break.

- the roles and types of work likely to be most affected or replaced by machine learning and robots

- and how will women be empowered or not socially by technology?

We quickly need in education to respond to the known data where women are already being left behind now. The attrition rate for example in teaching in England after two-three years is poor, and getting worse. What will government do to keep teachers teaching? Their value as role models is not captured in pupils’ exams results based entirely on knowledge transfer.

Our GCSEs this year go back to pure exam based testing, and remove applied coursework marking, and is likely to see lower attainment for girls than boys, say practitioners. Likely to leave girls behind at an earlier age.

“There is compelling evidence to suggest that girls in particular may be affected by the changes — as research suggests that boys perform more confidently when assessed by exams alone.”

Jennifer Tuckett spoke about what fairness might look like for female education in the Creative Industries. From school-leaver to returning mother, and retraining older women, appreciating the effects of gender in education is intrinsic to the future jobs market.

We also need broader public understanding of the loop of the impacts of technology, on the process and delivery of teaching itself, and as school management becomes increasingly important and is male dominated, how will changes in teaching affect women disproportionately? Fact delivery and testing can be done by machine, and supports current policy direction, but can a computer create a love of learning and teach humans how to think?

“There is a opportunity for a holistic synthesis of research into gender, the effect of tech on the workplace, the effect of technology on care roles, risks and opportunities.”

Delivering education to ensure women are not left behind, includes avoiding women going into education as teenagers now, to be led down routes without thinking of what they want and need in future. Regardless of work.

Education must adapt to changed employment markets, and the social and community effects of Brexit. If it does not, barriers will become embedded. Geographical, economic, language, familial, skills, and social exclusion.

In short

In summary, what is the government’s Brexit vision? We must know what they see five, 10, and for 25 years ahead, set against understanding the landscape as-is, in order to peg other policy to it.

With this foundation, what we know and what we estimate we don’t know yet can be planned for.

Once we know where we are going in policy, we can do a fit-gap to map how to get people there.

Estimate which skills gaps need filled and which do not. Where will change be hardest?

Change is not new. But there is current potential for massive long term economic and social lasting damage to our young people today. Government is hindered by short term political thinking, but it has a long-term responsibility to ensure children are not mis-educated because policy and the future environment are not aligned.

We deserve public, transparent, informed debate to plan our lives.

We enter the unknown of the education triangle at our peril; Brexit, underfunding, divisive structural policy, for the next ten years and beyond, without appropriate adjustment to pre-Brexit legislation and policy plans for the new world order.

The combined negative effects on employment at scale and at pace must be assessed with urgency, not by big Tech who will profit, but with an eye on future fairness, and public economic and social good. Academy sponsors, decision makers in curriculum choices, schools with limited funding, have no incentives to look to the wider world.

If we’re going to go it alone, we’d be better be robust as a society, and that can’t be just some of us, and can’t only be about skills as seen as having an tangible output.

All this discussion is framed by the premise that education’s aim is to prepare a future workforce for work, and that it is sustainable.

Policy is increasingly based on work that is measured by economic output. We must not leave out or behind those who do not, or cannot, or whose work is unmeasured yet contributes to the world.

‘The only future worth building includes everyone,’ said the Pope in a recent TedTalk.

What kind of future do you want to see yourself living in? Will we all work or will there be universal basic income? What will happen on housing, an ageing population, air pollution, prisons, free movement, migration, and health? What will keep communities together as their known world in employment, and family life, and support collapse? How will education enable children to discover their talents and passions?

Human beings are more than what we do. The sense of a country of who we are and what we stand for is about more than our employment or what we earn. And we cannot live on slogans alone.

Who do we think we in the UK will be after Brexit, needs real and substantial answers. What are we going to *do* and *be* in the world?

Without this vision, any mandate as voted for on June 9th, will be made in the dark and open to future objection writ large. ‘We’ must be inclusive based on a consensus, not simply a ‘mandate’.

Only with clear vision for all these facets fitting together in a model of how we will grow in all senses, will we be able to answer the question, is education preparing us [all] for the jobs of the future?

More than this, we must ask if education is preparing people for the lack of jobs, for changing relationships in our communities, with each other, and with machines.

Change is coming, Brexit or not. But Brexit has exacerbated the potential to miss opportunities, embed barriers, and see negative side-effects from changes already underway in employment, in an accelerated timeframe.

If our education policy today is not gearing up to that change, we must.