In recent weeks rebranding the poverty definitions and the living wage in the UK deservedly received more attention than the rebrand of the website NHS Choices into ‘nhs.uk.‘

The site that will be available only in England and Wales despite its domain name, will be the doorway to enter a personalised digital NHS offering.

As the plans proceed without public debate, I took some time to consider the proposal announced through the National Information Board (NIB) because it may be a gateway to a whole new world in our future NHS. And if not, will it be a big splash of cash but create nothing more than a storm-in-a-teacup?

In my previous post I’d addressed some barriers to digital access. Will this be another? What will it offer that isn’t on offer already today and how will the nhs.uk platform avoid the problems of its predecessor HealthSpace?

Everyone it seems is agreed, the coming cuts are going to be ruthless. So, like Alice, I’m curious. What is down the rabbit hole ahead?

What’s the move from NHS Choices to nhs.uk about?

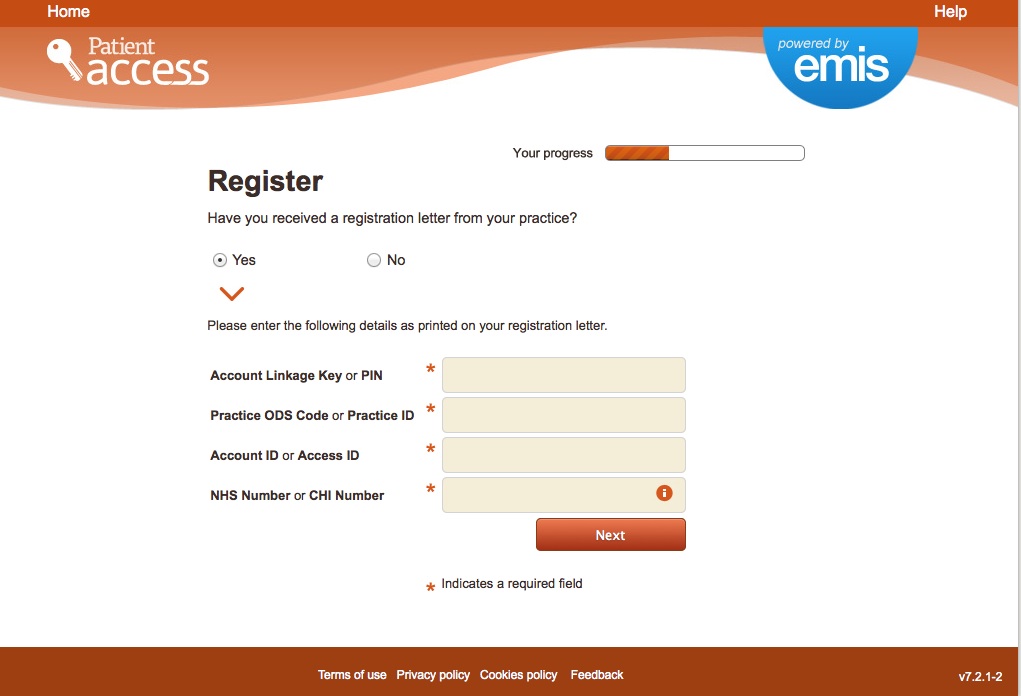

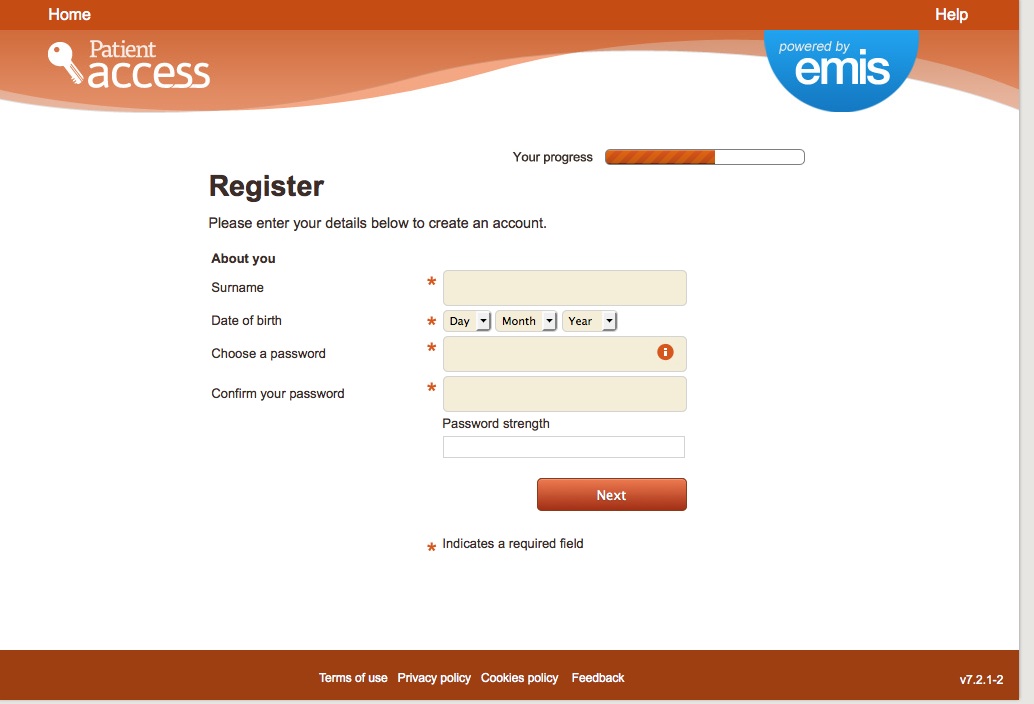

The new web platform nhs.uk would invite users to log on, using a system that requires identity, and if compulsory, would be another example of a barrier to access simply from a convenience point of view, even leaving digital security risks aside.

What will nhs.uk offer to incentivise users and offer benefit as a trade off against these risks, to go down the new path into the unknown and like it?

“At the heart of the domain , will be the development of nhs.uk into a new integrated health and care digital platform that will be a source of access to information, directorate, national services and locally accredited applications.”

In that there is nothing new compared with information, top down governance and signposting done by NHS Choices today.

What else?

“Nhs.uk will also become the citizen ’s gateway to the creation of their own personal health record, drawing on information from the electronic health records in primary and secondary care.”

nhs.uk will be an access point to patient personal confidential records

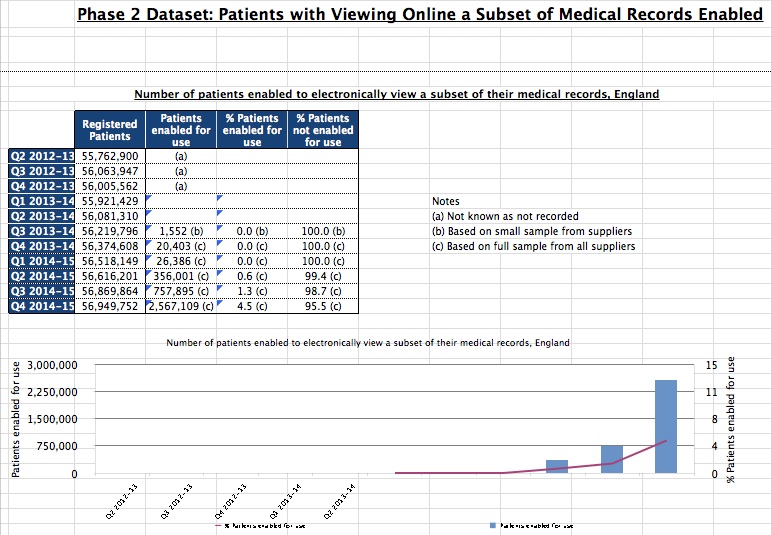

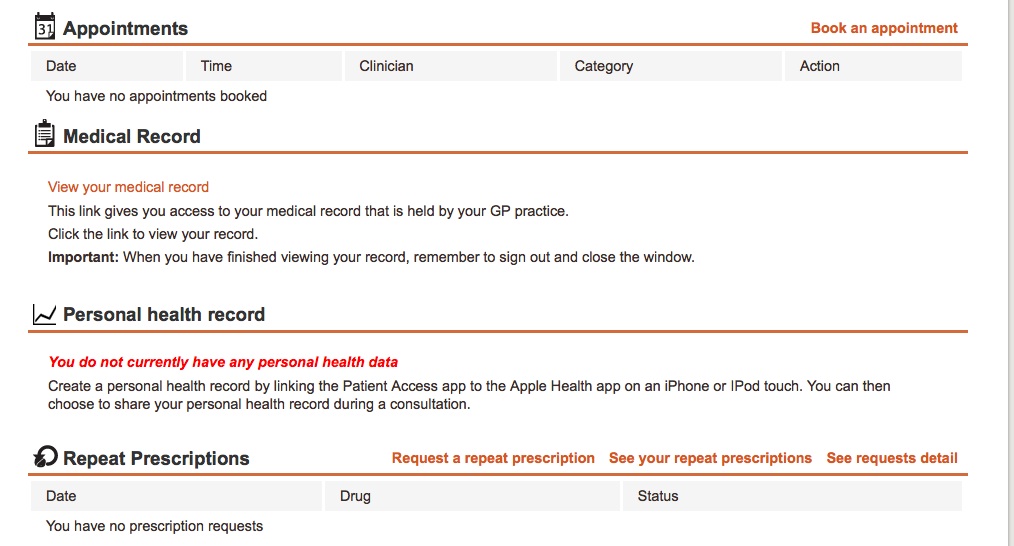

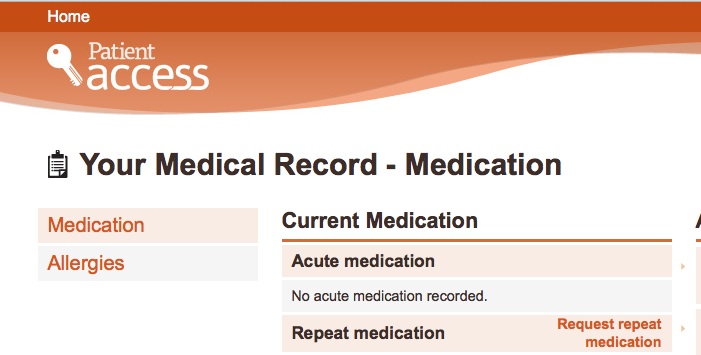

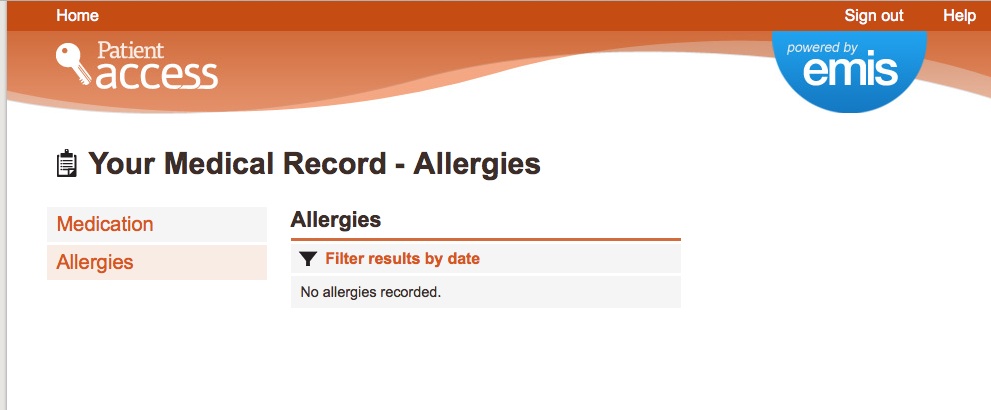

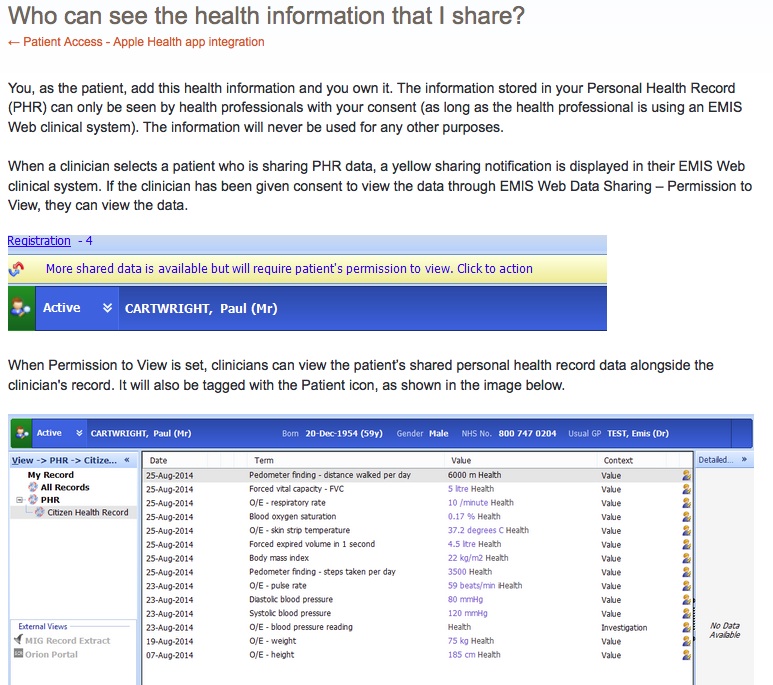

Today’s patient online we are told offers 97% of patients access to their own GP created records access. So what will nhs.uk offer more than is supposed to be on offer already today? Adding wearables data into the health record is already possible for some EMIS users, so again, that won’t be new. It does state it will draw on both primary and secondary records which means getting some sort of interoperability to show both hospital systems data and GP records. How will the platform do this?

Until care.data many people didn’t know their hospital record was stored anywhere outside the hospital. In all the care.data debates the public was told that HES/SUS was not like a normal record in the sense we think of it. So what system will secondary care records come from? [Some places may have far to go. My local hospital pushes patients round with beige paper folders.] The answer appears to be an unpublished known or an unknown.

What else?

nhs.uk will be an access point to tailored ‘signposting’ of services

In addition to access to your personal medical records in the new “pull not push” process the nhs.uk platform will also offer information and services, in effect ‘advertising’ local services, to draw users to want to use it, not force its use. And through the power of web tracking tools combined with log in, it can all be ‘tailored’ or ‘targeted’ to you, the user.

“Creating an account will let you save information, receive emails on your chosen topics and health goals and comment on our content.”

Do you want to receive emails on your chosen topics or comment on content today? How does it offer more than can already be done by signing up now to NHS Choices?

NHS Choices today already offers information on local services, on care provision and symptoms’ checker.

What else?

Future nhs.uk users will be able to “Find, Book, Apply, Pay, Order, Register, Report and Access,” according to the NIB platform headers.

“Convenient digital transactions will be offered like ordering and paying for prescriptions, registering with GPs, claiming funds for treatment abroad, registering as an organ and blood donor and reporting the side effects of drugs . This new transactional focus will complement nhs.uk’s existing role as the authoritative source of condition and treatment information, NHS services and health and care quality information.

“This will enable citizens to communicate with clinicians and practices via email, secure video links and fill out pre-consultation questionnaires. They will also be able to include data from their personal applications and wearable devices in their personal record. Personal health records will be able to be linked with care accounts to help people manage their personal budget.”

Let’s consider those future offerings more carefully.

Separating out the the transactions that for most people will be one off, extremely rare or never events (my blue) leaves other activities which you can already do or will do via the patient online programme (in purple).

The question is that although video and email are not yet widespread where they do work today and would in future, would they not be done via a GP practice system, not a centralised service? Or is the plan not that you could have an online consultation with ‘your’ named GP through nhs.uk but perhaps just ‘any’ GP from a centrally provided GP pool? Something like this?

That leaves two other things, which are both payment tools (my bold).

i. digital transactions will be offered like ordering and paying for prescriptions

ii. …linked with care accounts to help people manage their personal budget.”

Is the core of the new offering about managing money at individual and central level?

Beverly Bryant, Director of Strategic Systems and Technology at NHS England, said at the #kfdigi2015 June 16th event, that implementing these conveniences had costs saving benefits as well: “The driver is customer service, but when you do it it actually costs less.”

How are GP consultations to cost less, significantly less, to be really cost effective compared with the central platform to enable it to happen, when the GP time is the most valuable part and remains unchanged spent on the patient consultation and paperwork and referral for example?

That most valuable part to the patient, may be seen as what is most costly to ‘the system’.

If the emphasis is on the service saving money, it’s not clear what is in it for people to want to use it and it risks becoming another Healthspace, a high cost top down IT rollout without a clear customer driven need.

The stated aim is that it will personalise the user content and experience.

That gives the impression that the person using the system will get access to information and benefits unique and relevant to them.

If this is to be something patients want to use (pull) and are not to be forced to use (push) I wonder what’s really at its core, what’s in it for them, that is truly new and not part of the existing NHS Choices and Patient online offering?

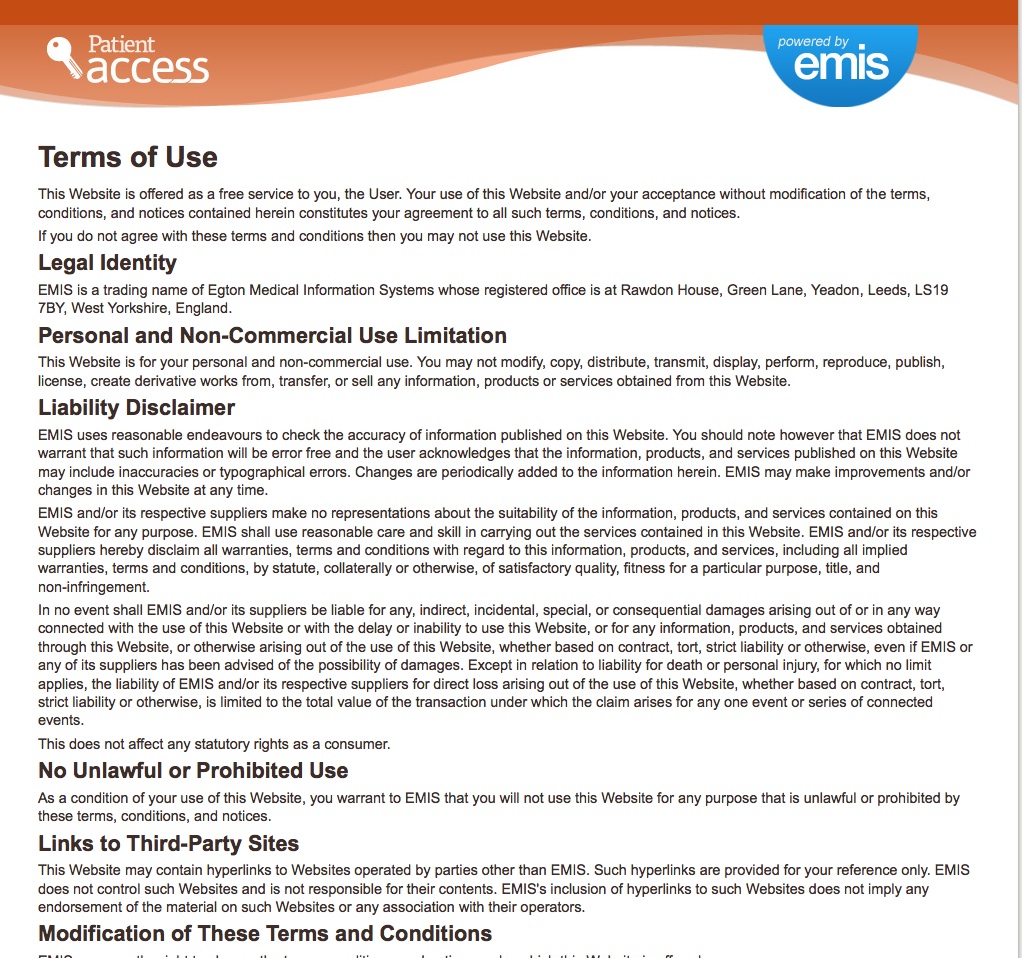

What kind of personalised tailoring do today’s NHS Choices Ts&Cs sign users up to?

“Any information provided, or any information the NHS.uk site may infer from it, are used to provide content and information to your account pages or, if you choose to, by email. Users may also be invited to take part in surveys if signed up for emails.

“You will have an option to submit personal information, including postcode, age, date of birth, phone number, email address, mobile phone number. In addition you may submit information about your diet and lifestyle, including drinking or exercise habits.”

“Additionally, you may submit health information, including your height and weight, or declare your interest in one or more health goals, conditions or treatments. “

“With your permission, academic institutions may occasionally use our data in relevant studies. In these instances, we shall inform you in advance and you will have the choice to opt out of the study. The information that is used will be made anonymous and will be confidential.”

Today’s NHS Choices terms and conditions say that “we shall inform you in advance and you will have the choice to opt out of the study.”

If that happens already and the NHS is honest about its intent to give patients that opt out right whether to take part in studies using data gathered from registered users of NHS Choices, why is it failing to do so for the 700,000 objections to secondary use of personal data via HSCIC?

If the future system is all about personal choice NIB should perhaps start by enforcing action over the choice the public may have already made in the past.

Past lessons learned – platforms and HealthSpace

In the past, the previous NHS personal platform, HealthSpace, came in for some fairly straightforward criticism including that it offered too little functionality.

The Devil’s in the Detail remarks are as relevant today on what users want as they were in 2010. It looked at the then available Summary Care Record (prescriptions allergies and reactions) and the web platform HealthSpace which tried to create a way for users to access it.

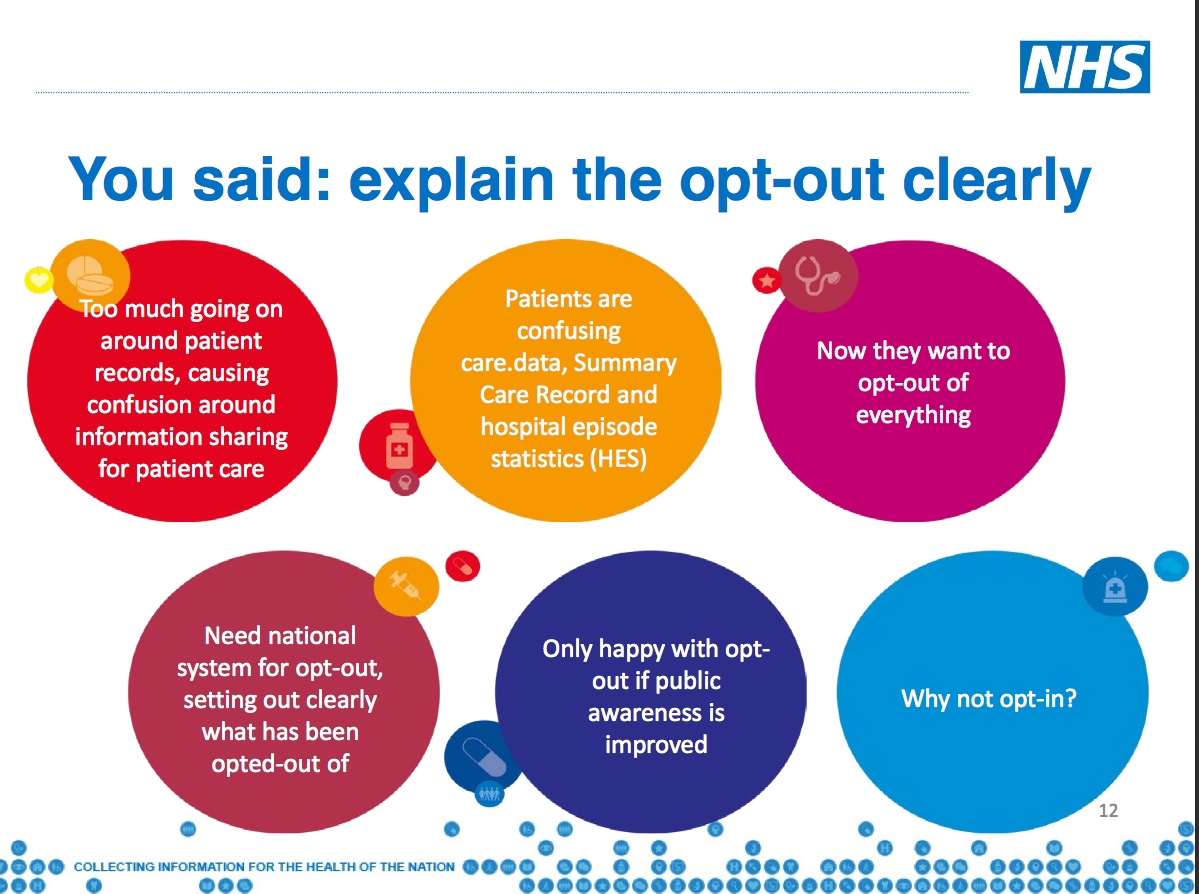

Past questions from Healthspace remain unanswered for today’s care.data or indeed the future nhs.uk data: What happens if there is a mistake in the record and the patient wants it deleted? How will access be given to third party carers/users on behalf of individuals without capacity to consent to their records access?

Reasons given by non-users of HealthSpace included lack of interest in managing their health in this way, a perception that health information was the realm of health professionals and lack of interest or confidence in using IT.

“In summary, these findings show that ‘self management’ is a much more complex, dynamic, and socially embedded activity than original policy documents and technical specifications appear to have assumed.”

What lessons have been learned? People today are still questioning the value of a centrally imposed system. Are they being listened to?

Digital Health reported that Maurice Smith, GP and governing body member for Liverpool CCG, speaking in a session on self-care platforms at the King’s Fund event he said that driving people towards one national hub for online services was not an option he would prefer and that he had no objection to a national portal, “but if you try drive everybody to a national portal and expect everybody to be happy with that I think you will be disappointed.”

How will the past problems that hit Healthspace be avoided for the future?

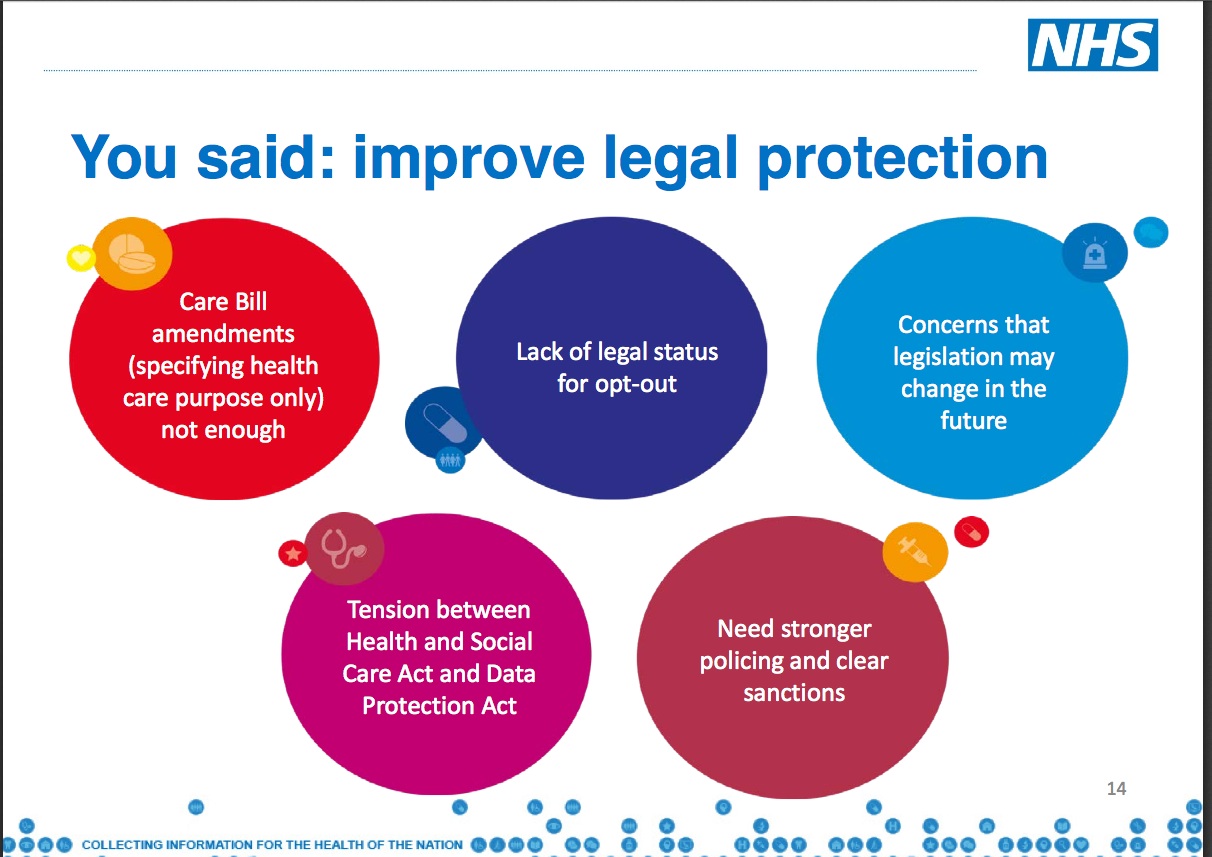

How will the powers-at-be avoid repeating the same problems for its ongoing roll out of care.data and future projects? I have asked this same question to NHS England/NIB leaders three times in the last year and it remains unanswered.

How will you tell patients in advance of any future changes who will access their data records behind the scenes, for what purpose, to future proof any programmes that plan to use the data?

One of the Healthspace 2010 concerns was: “Efforts of local teams to find creative new uses for the SCR sat in uneasy tension with implicit or explicit allegations of ‘scope creep’.”

Any programme using records can’t ethically sign users up to one thing and change it later without informing them before the change. Who will pay for that and how will it be done? care.data pilots, I’d want that answered before starting pilot communications.

As an example of changes to ‘what’ or content scope screep, future plans will see ‘social care flags added’ to the SCR record, states p.17 of the NIB 2020 timeline. What’s the ‘discovery for the use of genomic data complete’ about on p.11? Scope creep of ‘who’ will access records, is very current. Recent changes allow pharmacists to access the SCR yet the change went by with little public discussion. Will they in future see social care flags or mental health data under their SCR access? Do I trust the chemist as I trust a GP?

Changes without adequate public consultation and communication cause surprises. Bad idea. Sir Nick Partridge said ensuring ‘no surprises’ is key to citizens’ trust after the audit of HES/SUS data uses. He is right.

The core at the heart of this nhs.uk plan is that it needs to be used by people, and enough people to make the investment vs cost worthwhile. That is what Healthspace failed to achieve.

The change you want to see doesn’t address the needs of the user as a change issue. (slide 4) This is all imposed change. Not user need-driven change.

Dear NIB, done this way seems to ignore learning from Healthspace. The evidence shown is self-referring to Dr. Foster and NHS Choices. The only other two listed are from Wisconsin and the Netherlands, hardly comparable models of UK lifestyle or healthcare systems.

What is really behind the new front door of the nhs.uk platform?

The future nhs.uk looks very much as though it seeks to provide a central front door to data access, in effect an expanded Summary Care Record (GP and secondary care records) – all medical records for direct care – together with a way for users to add their own wider user data.

Will nhs.uk also allow individuals to share their data with digital service providers of other kinds through the nhs.uk platform and apps? Will their data be mined to offer a personalised front door of tailored information and service nudges? Will patients be profiled to know their health needs, use and costs?

If yes, then who will be doing the mining and who will be using that data for what purposes?

If not, then what value will this service offer if it is not personal?

What will drive the need to log on to another new platform, compared with using the existing services of patient online today to access our health records, access GPs via video tools, and without any log-in requirement, browse similar content of information and nudges towards local services offered via NHS Choices today?

If this is core to the future of our “patient experience” of the NHS the public should be given the full and transparent facts to understand where’s the public benefit and the business case for nhs.uk, and what lies behind the change expected via online GP consultations.

This NIB programme is building the foundation of the NHS offering for the next ten years. What kind of NHS are the NIB and NHS England planning for our children and our retirement through their current digital designs?

If the significant difference behind the new offering for nhs.uk platform is going to be the key change from what HealthSpace offered and separate from what patient online already offers it appears to be around managing cost and payments, not delivering any better user service.

Managing more of our payments with pharmacies and personalised budgets would reflect the talk of a push towards patient-responsible-self-management direction of travel for the NHS as a whole.

More use of personal budgets is after all what Simon Stevens called a “radical new option” and we would expect to see “wider scale rollout of successful projects is envisaged from 2016-17″.

When the system will have finely drawn profiles of its users, will it have any effect for individuals in our universal risk-shared system? Will a wider roll out of personalised budgets mean more choice or could it start to mirror a private insurance system in which a detailed user profile would determine your level of risk and personal budget once reached, mean no more service?

What I’d like to see and why

To date, transparency has a poor track record on sharing central IT/change programme business plans. While saying one thing, another happens in practice. Can that be changed? Why all the effort on NHS Citizen and ‘listening’, if the public is not to be engaged in ‘grown up debate‘ to understand the single biggest driver of planned service changes today: cost.

It’s at best patronising in the extreme, to prevent the public from seeing plans which spend public money.

We risk a wasteful, wearing repeat of the past top down failure of an imposed NPfIT-style HealthSpace, spending public money on a project which purports to be designed to save it.

To understand the practical future we can look back to avoid what didn’t work and compare with current plans. I’d suggest they should spell out very clearly what were the failures of Healthspace, and why is nhs.uk different.

If the site will offer an additional new pathway to access services than we already have, it will cost more, not less. If it has genuine expected cost reduction compared with today, where precisely will it come from?

I’d suggest you publish the detailed business plan for the nhs.uk platform and have the debate up front. Not only the headline numbers towards the end of these slides, but where and how it fits together in the big picture of Stevens’ “radical new option”. This is public money and you *need* the public on side for it to work.

Publish the business cases for the NIB plans before the public engagement meet ups, because otherwise what facts will opinion be based on?

What discussion can be of value without them, when we are continually told by leadership those very details are at the crux of needed change – the affordability of the future of the UK health and care system?

Now, as with past projects, The Devil’s in the Detail.

***

NIB detail on nhs.uk and other concepts: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/437067/nib-delivering.pdf

The Devil’s in the Detail: Final report of the independent evaluation of the Summary Care Record and HealthSpace programmes 2010