I wrote this post in July 2014, before the introduction of the universal infant free school meals programme (UIFSM) and before I put my interest in data to work. Here’s an updated version. My opinion why I feel it is vital that public health and socio economic research should create an evidence base that justifies or refutes policy.

I wondered last year whether our children’s health and the impact of UIFSM was simply a political football, which was given as a concession in the last Parliament, rushed through to get checked-off, without being properly checked out first?

How is UIFSM Entitlement Measured and What Data do we Have?

I have wondered over this year how the new policy which labels more children as entitled to free school meals may affect public health and social research.

The Free School Meal (FSM) indicator has been commonly used as a socio-economic indicator.

In fact, there is still a practical difference within the ‘free school meals’ label.

In my county, West Sussex, those who are entitled to FSM beyond infants must actively register online. Although every child in Reception, Years 1 and 2 is automatically entitled to UIFSM, parents in receipt of the state income benefits must actively register with county to have an FSM eligibility check, so that schools receive the Pupil Premium. Strangely having to register for ‘Free School Meals’ where others need not under automatic entitlement in infants – because it’s not called as it probably should be ‘sign up for Pupil Premium’ which benefits the school budget and one hopes, the child with support or services they would not otherwise get.

Registering for a free school meal eligibility check could raise an extra grant of £1,320 per year, per child, for the child’s primary school, or £935 per child for secondary schools, to fund valuable support like extra tuition, additional teaching staff or after school activities. [source]

Researchers will need to give up the FSM indicator used as an adopted socio-economic function in age groups under 8. Over 8 (once children leave infants) only those entitled due to welfare status and actively registered will have the FSM label. Any comparative research can only use the Pupil Premium status, but as the benefits which permit applying for it changed too, comparison will be hard. An obvious and important change to remember measuring the effects of the policy change have had.

One year on, I’d also like to understand how research may capture the changes of children’s experience in reality.

There are challenges in this; not least getting hold of the data. Given that private providers may not all be open to provision of information, do not provide data as open data, and separately, are not subject to the Freedom of Information Act, we may not be able to find out the facts around the changes and how catering meets the needs of some of our youngest children.

If it can be hard to access information from private providers held by them, it can be even harder to do research in the public interest using information about them. In my local area Capita manages a local database and the meal providers are private companies. (No longer staff directly employed and accountable to schools as once was).

[updated Aug 30 HT Owen Boswara for the link to the Guardian article in March 2015 reporting that there are examples where this has cut the Pupil Premium uptake]

Whom does it benefit most?

Quantity or Quality and Equality?

In last year’s post I considered food quality and profit for the meal providers.

I would now be interested to see research on what changes if any there have been in the profit and costs of school meal providers since the UIFSM introduction and what benefits we see for them compared with children.

4 in 10 children are classed as living in poverty but may not meet welfare benefit criteria according to Nick Clegg, on LBC on Sept 5th 2014. That was a scandalous admission of the whole social system failure on child poverty. Hats off to the nine year-old who asked good questions last year.

The entitlement is also not applied to all primary children equally, but infants only. So within one family some children are now entitled and others are not.

I wonder if this has reshaped family evening meals for those who do not quite qualify for FSM, where now one child has already ‘had a hot meal today’ and others have not?

The whole programme of child health in school is not only unequal in application to children by age, but is not made to apply to all schools equally.

Jamie Oliver did his darnedest to educate and bring in change, showing school meals needed improvement in quality across the board. What has happened to those quality improvements he championed? Abandoned at least in free school where schools are exempt from national standards. [update: Aug 25 his recent comment].

There is clearly need when so many children are growing up in an unfairly distributed society of have and have-not, but the gap seems to be ever wider. Is Jamie right that in England eating well is a middle class concern? Is it impossible in this country to eat cheaply and eat well?

In summary, I welcome anything that will help families feed their children well. But do free school dinners necessarily mean good nutrition? The work by the Trussel Trust and others, shows what desperate measures are needed to help children who need it most and simply ‘a free school meal’ is not necessarily a ticket to good food, without rigorous application and monitoring of standards, including reviewing in schools what is offered vs what children actually eat from the offering.

Where is the analysis for people based policy that will tackle the causes of need, and assess if those needs are being met?

Evidence based understanding

It appears there were pilots and trials but we hadn’t heard much about them before September 2014. I agreed with then MP David Laws, on the closure of school kitchens, but from my own experience, the UIFSM programme lacked adequate infrastructure and education before it began.

Mr. Laws MP said,

“It is going to be one of the landmark social achievements of this coalition government – good for attainment, good for health, great for British food, and good for hard working families. Ignore the critics who want to snipe from the sidelines.”

I don’t want to be a critic from the sidelines, I’d like to be an informed citizen and a parent and know that this programme brought in good food for good health. Good for very child, but I’d like to know it brought the necessary change for the children who really needed it. [Ignoring his comment on hard working families, which indicates some sort of value judgement and out of place.]

Like these people and their FOIs, I want to ask and understand. Will this have a positive effect on the nutrition children get, which may be inadequate today?

How will we measure if UIFSM is beneficial to children who need it most?

Data used well gives insights into society that researchers should use to learn from and make policy recommendations.

The data from the meal providers and the data on UIFSM indicators as well as Pupil Premium need looked at together. That won’t be easy.

What is accessible is the data held by the DfE but that may also be “off” for true comparison because the need for active sign up is reportedly patchy.

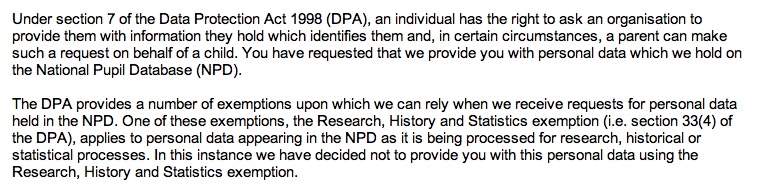

Data on individual pupils needs used with great care due to these measurement changes in practice as well as its sensitivity. To measure that the policy is working needs careful study accounting for all the different factors that changed at the same time. The NPD has pupil premium tracked but has its uptake affected the numbers as to make it a useful comparator?

Using this administrative data — aggregated and open data — and at other detailed levels for bona fide research is vital to understand if policies work. The use of administrative data for research has widespread public support in the public interest, as long as it is done well and not for commercial use.

To make it more usefully available, and as I posted previously, I believe the Department of Education should shape up its current practices in its capacity as the data processor and controller of the National Pupil Database to be fit for the 21st century if it is to meet public expectations of how it should be done.

Pupils and parents should be encouraged to become more aware about information used about them, in the same way that the public should be encouraged to understand how that information is being used to shape policy.

At the same time as access to state held data could be improved, we should also demand that access to information for public health and social benefit should be required from private providers. Public researchers must be prepare to stand up and defend this need, especially at a time when Freedom of Information is also under threat and should in fact expanded to cover private providers like these, not be restricted further.

Put together, this data in secure settings with transparent oversight could be invaluable in the public interest. Being seen to do things well and seeing public benefits from the data will also future-proof public trust that is vital to research. It could be better for everyone.

So how and when will we find out how the UIFSM policy change made a difference?

What did UIFSM ever do for us?

At a time when so many changes have taken place around child health, education, poverty and its measurement it is vital that public health and socio economic research creates an evidence base that justifies or refutes policy.

In some ways, neutral academic researchers play the role of referee.

There are simple practical things which UIFSM policy ignores, such as 4 year-olds starting school usually start on packed lunch only for a half term to get to grips with the basics of school, without having to manage trays and getting help to cut up food. The length of time they need for a hot meal is longer than packed lunch. How these things have affected starting school is intangible.

Other tangible concerns need more attention, many of which have been reported in drips of similar feedback such as reduced school hall and gym access affecting all primary age children (not only infants) because the space needs to be used for longer due to the increase in numbers eating hot meals.

Research to understand the availability of facilities and time spent on sport in schools since the introduction of UIFSM will be interesting to look at together with child obesity rates.

The child poverty measurements also moved this year. How will this influence our perception of poverty and policies that are designed to tackle it?

Have we got the data to analyse these policy changes? Have we got analysis of the policy changes to see if they benefit children?

As a parent and citizen, I’d like to understand who positions the goalposts in these important public policies and why.

And who is keeping count of the score?

****

image source: The Independent

refs: Helen Barnard, JRF. http://www.jrf.org.uk/blog/2015/06/cutting-child-benefit-increasing-free-childcare-where-poverty-test

![Building Public Trust [5]: Future solutions for health data sharing in care.data](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/caredatatimeline-637x372.jpg)

![Building Public Trust in care.data datasharing [3]: three steps to begin to build trust](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/optout_ppt-672x372.jpg)

![Building Public Trust [2]: a detailed approach to understanding Public Trust in data sharing](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Trust-e1426443553441-672x372.jpg)

![Building Public Trust in care.data sharing [1]: Seven step summary to a new approach](https://jenpersson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/edison1-672x372.jpg)